I was raised in segregated North Carolina in a middle-class African American family. My parents were both educators. I attended supposedly separate but equal schools, sat in the back of the bus, drank from black-only water fountains, sat in the balcony of theaters, and could not enter certain facilities. Contact with whites occurred only when I ventured out of my neighborhood to go downtown to shop or to pay bills. Still, I did not dislike white people with whom I had little interaction and who I viewed as privileged.

I participated in civil rights marches and sit-ins. I learned about the Peace Corps from a recruiter while attending North Carolina College for Negroes in Durham NC, where I received an art education degree with a minor in special education in 1968.

Two weeks after graduating I was on a plane headed for Peace Corps staging in Philadelphia. The following week I boarded a charter plane for Sierra Leone, where I would serve as a primary education volunteer for three years. I was one of four African American trainees in a group of 139 recruits. We had similar backgrounds and bonded during staging. To our surprise the four of us were separated upon arrival in Sierra Leone and sent to training sites in different parts of the country. I trained in Bo, in the Southern Province.

Training was a grind. My closest friends were the three African language/cultural instructors. The instructors were interested in my life experiences as a descendant of slaves in what the instructors called a white country. I learned from the instructors that many educated Africans had distorted impressions of African Americans because of the stereotypes of poverty, crime, and backwardness portrayed in books and the media.

I wanted to learn about rural African life, how daily challenges like food, housing, and illnesses were addressed with scarce resources. As an art education major, I was curious about traditional art, religion, music, and culture. My relationship with the three instructors was a perfect match. While I was also friends with several white trainees, I did not participate in their social gatherings. I found some of their comments to be insensitive. Two questions from fellow volunteers stood out as maybe being racist. One volunteer asked me if Blacks in the south ate the same African food. Another volunteer asked me, “How can you tell from a black child’s face and eyes when they are learning?”

Sembehun, my placement site, was very rural with minimal infrastructure and no electricity, running water, stores, cars, etc. I arrived by lorry on a Saturday afternoon. To me, Sembehun was idyllic. The welcome was overwhelming. Children hollered, “Peace Corps done come oh.” I was welcomed by Chief Soloku and headmaster Amara Mustapha. Children ran to fetch water. Others swept my little mud house while a neighbor prepared food. I felt like I was being welcomed home after a long time away. The villagers were surprised I spoke enough Mende to greet them in their language while expressing my excitement to be there. The next day, I was welcomed with a reception including traditional dance, pepper soup, and cola nuts. I spoke and said I was honored to be there, and I would do all I could to help them achieve their goals. For the first time in my life, I was a VIP. One of my neighbors asked me why my skin was yellow while other Peace Corps volunteers had white skin. I later learned that the color of skin did not mean much to people in Sembehun. As the only Peace Corps volunteer in a village of 900, I was a valued asset, and I felt my neighbors would stand between me and any danger, natural or manmade.

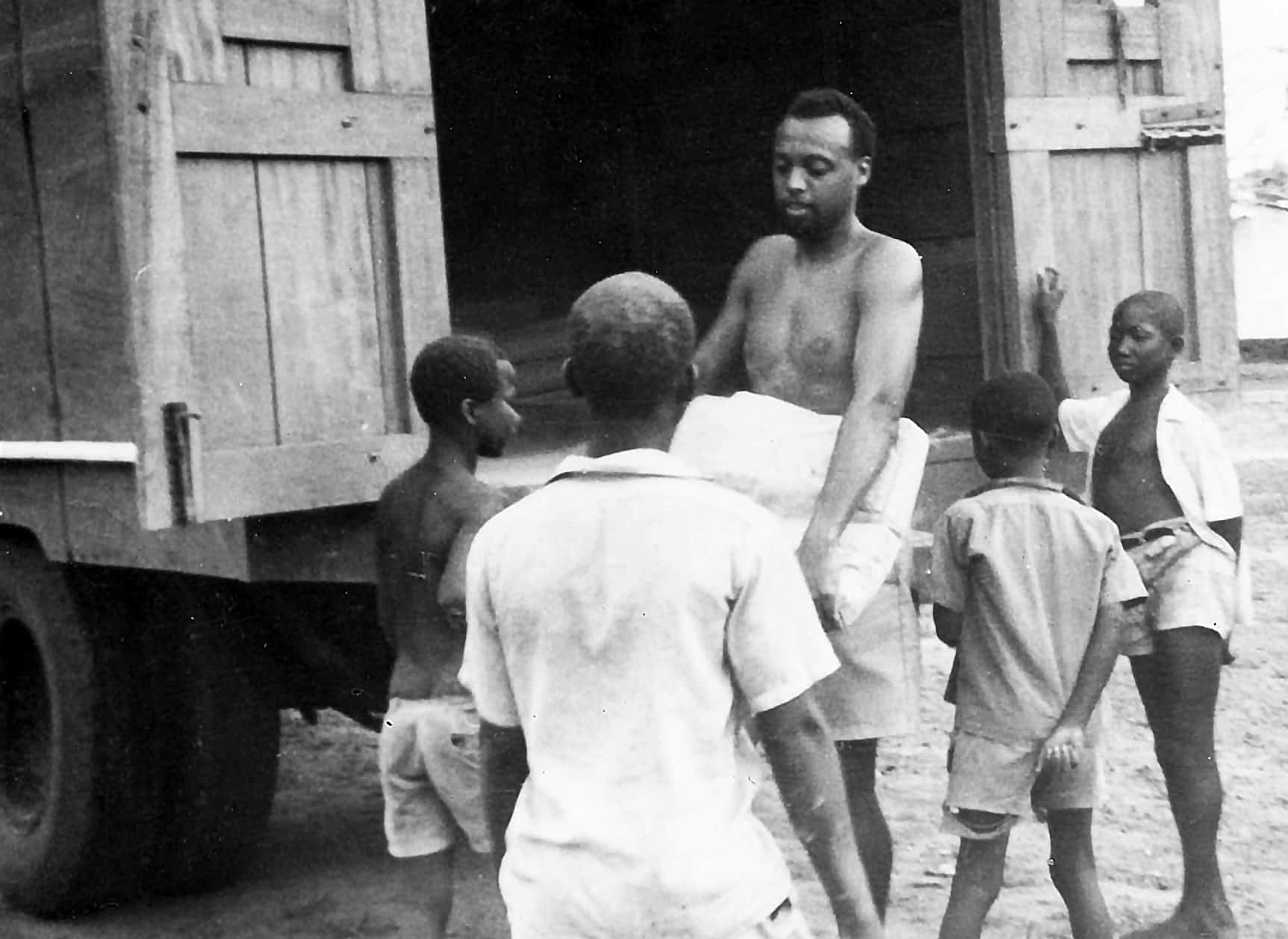

Volunteers in the 1960s were expected to have three focus areas. My first job was to teach and help train teachers. My second focus was to finish construction of the school the previous volunteer had started. Chief Soloku arranged a meeting for me with female leaders to discuss their priorities. The women wanted potable water, either from deep wells or pipe-borne. I learned that women and children spent half of each day carrying water for drinking and cooking, from a small creek a mile from the village. Constructing a water system and finishing the school would cost five to seven thousand dollars in materials each. I saw these three initiatives as being possible in two years. Little did I know that in addition to planning and coordinating I had to do resource mobilization. With the help of Kappa Alpha Psi (my fraternity), CARE International, the American Embassy, and Muslim Brotherhood of Saudia Arabia, I was able to generate the funds needed. I also contributed personal resources.

I was what volunteers referred to as a “site-rat.” I never wanted to leave my village. Sembehun with all its needs, wants, and challenges was my paradise. The Chief assigned revolving workers to me who reported for their work assignments every two weeks. My biggest challenge was training and supervising while teaching. I wore out my trusted bicycle in eighteen months, sometime travelling twenty miles in a day on rutted dirt roads. The school was completed in year one. Other projects took longer. I needed to extend my service for a third year. I had met another volunteer thirty-six miles away who I would eventually marry at the end of our Peace Corps service.

At my going away party I was presented with a variety of gifts. The Paramount Chief asked me to keep the key to the main room in my house as he knew I would return to Sembehun. The Chief said I was a son of the soil. I was always welcome. Sembehun was my home. The Chief called my party a send-off instead of a going away because he knew I would return. The Chief said I was not like other volunteers.

After completing my service, I was hired as Peace Corps staff in Sierra Leone and Ghana from 1971 to 1976. I returned to Sembehun often, even taking our children and my parents to visit. It was like going home.