My story begins in 1963, when I moved from my village to a nearby town for high school. With no place to stay, I convinced two Peace Corps teachers, Nyle Kardatzke and John Rude, to hire me as a guard and let me live in their home. My English improved quickly, and I later graduated from Haile Selassie I University in Addis Ababa.

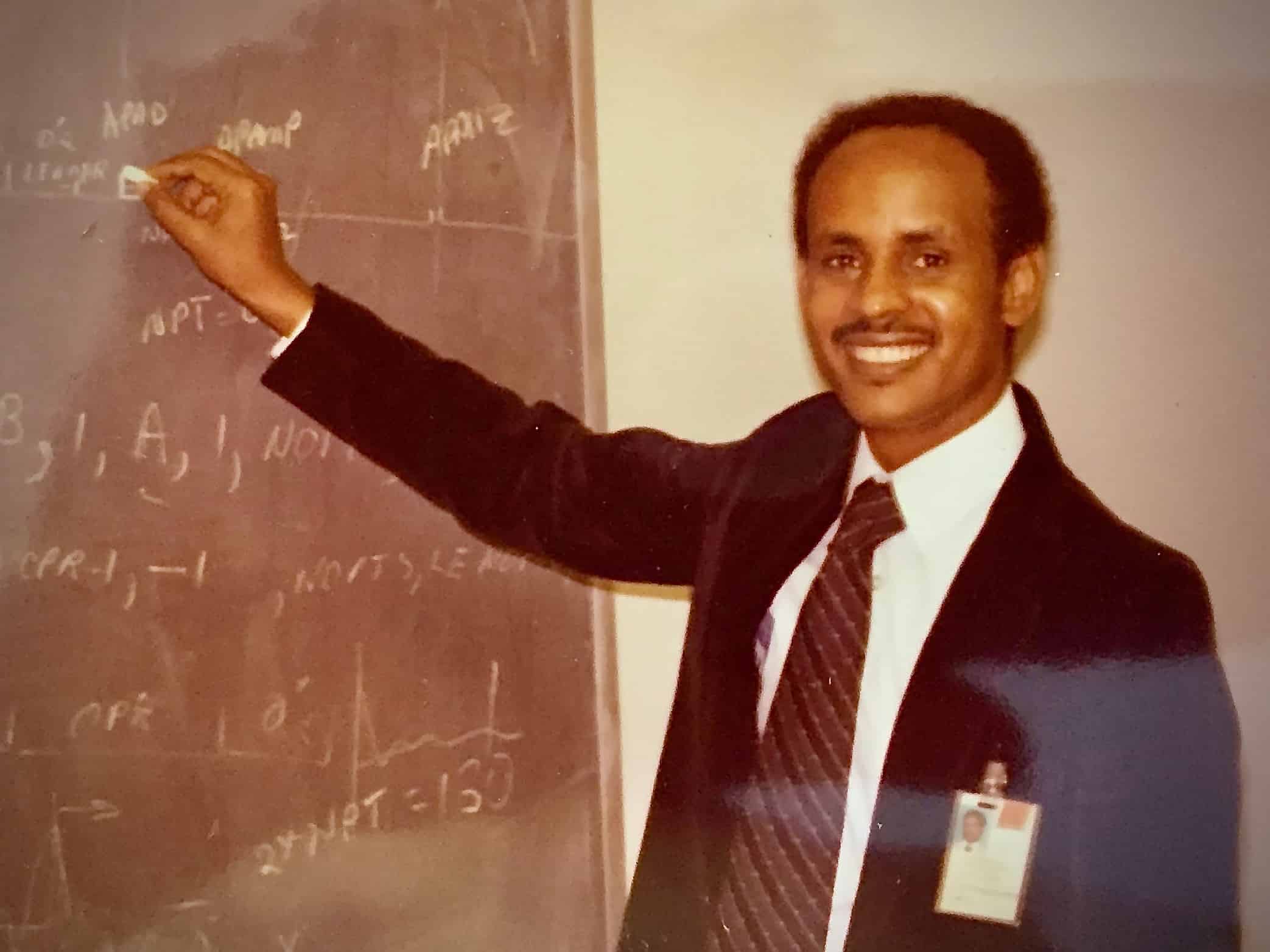

After graduation, I worked as a geophysicist for a Canadian oil company and learned Fortran on punch cards and an IBM mainframe. At the time, no one imagined desktop computers, mobile phones, or the Internet, let alone writing my language, Tigrinya, with a computer.

Over the next four decades, I worked to keep pace with the computer revolution. I also focused on local languages. Tigrinya and Amharic, derived from the ancient Ge’ez script, use a unique alphabet with 252 consonant-vowel combinations—far more than the 52 keys on an English keyboard. Finding a way to type these characters became my lifelong technical challenge.

A breakthrough came during a visit to an Apple Computer store with my former teacher, John Rude. John asked me to visit the store because he had learned how Japanese programmers used phonetic combinations stored in a character generator chip for word processing. Inspired, I began experimenting with hexadecimal coding and, in 1982, produced my first Tigrinya words on an Apple II computer. I shared instructions on how to type with Eritreans who live in the U.S.

Apple’s Basic program was too slow, however, so I learned how to code with Assembly, creating a faster system that used English letters to represent the sounds of Tigrinya. For example, by typing “Yemane” with consonants and numeric vowels—like “Y1M4N1” —the correct Ge’ez characters appeared on the screen. I named my new program “Ge’ez Gate.”

In 1985, the Apple Macintosh’s graphical transformed the process of font-shaping. I used MacWrite to create my fourth generation of fonts. My Macintosh word processing was competing with other systems that used software called “C.” By 1987, I had published my first Tigrinya book, short-circuiting traditional typesetting, which used metal letters to typeset using mechanized printing. Composition with various Ge’ez software programs quickly gained momentum among people familiar with computers. Ethiopian programmers soon developed Amharic-language versions of Ge’ez-Gate as well.

The real turning point came in 1991 with Unicode, which standardized non-Roman scripts, such as Japanese, Chinese, and Russian. I quickly adopted Unicode—my sixth coding language—and redesigned Ge’ez Gate. Now users could type vowels directly, instead of using numbers. Unicode also made my software compatible with DOS and Windows, enabling typing with Tigrinya and Amharic on either Apple or Windows platforms.

Now I had done all I could with computer programming tools. Today, I use Ge’ez-Gate software to teach immigrant children how to read and write using the languages their parents know. Over the years, I learned an important lesson: that languages and cultures never grow stagnant. All cultures will only be enriched by spreading the use of language through travel, mutual respect, and the struggle to survive.

Across 40 years, I had many difficult moments, but I was strengthened by the dedication of fellow programmers and inspired Peace Corps teachers. Together, we helped bring ancient written languages into the digital world. I consider it a privilege to serve others through my mastery of technology.

Yemane was a student of Peace Corps Volunteers in Eritrea – 1963-1965 Now he a software engineer living in Houston, Texas