Growing up as a navy brat, moving constantly, I fancied myself endlessly adaptable, easily making new friends and picking up the local slang, the fashions, the culture. But who was I really, under all those changes? Every life anywhere seemed possible, none preferable; I changed college majors four times.

The Peace Corps, beyond the challenge of a really different language and culture, offered a two-year postponement of choosing a life. How about somewhere in South America, the recruiter said. No, I wanted Turkey—I had glimpsed its mysterious ruins and dazzling Istanbul during a Junior Year Abroad road trip, and South America looked dull by comparison.

In 1964, Gaziantep was not Istanbul, to put it mildly. Its two paved streets crossed at the town’s only stoplight. Other streets were gravel or cobblestones that ruined the little heels I wore as a nervous English teacher at an overcrowded junior high school in the town’s poorest district. Still, the provincial capital’s 60,000 inhabitants made it the largest town in southeast Turkey, an agricultural market center at the intersection of smuggling routes to Syria and the roads forged eons ago by countless armies marching east or west below the Taurus mountains.

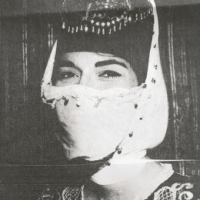

On our numerous school vacations, my roommates and I explored the ruins those armies left behind, as well as nearby small rural villages. In those villages, and in Gaziantep, we were occasionally invited to weddings. I was dazzled by the brides’ elaborate gowns, often of heavy red or blue velvet with complex floral overlays of cardboard covered in silver thread and sequins. I decided I wanted one to wear back at home on dressy occasions. But the floor-length caftans were all handmade labors of love by the bride and her friends and family, not sold in stores. And I wasn’t about to ask the women we knew to sell their treasured gowns.

To reach my school, I walked every day through the household goods market, including the shops for brass and copper cooking pots and trays. One or two also sold “old things” they said poor rural villagers brought in to trade for those pots, and I had become a regular customer for copper bowls and plates engraved with owners’ marks of centuries past. They were affordable even on my Peace Corps allowance.

One day I spotted this dress hanging on one shop wall. The elderly dealer said it had just come in, it was very old, and he wanted the equivalent of $20 for it, an astronomical sum. I’m sure he wondered if I, a single foreign woman, was a respectable person. But observing bargaining protocol, I admired the dress, had some hot sweet tea in little hourglass-shaped glasses, agreed the price was fair but I just couldn’t afford it, and left. The next day the dealer pointed out the bloodstains on the dress’s interior rear—proof, he said, that the bride had been a virgin. I really ought to buy this dress, he said, to show Americans the purity of Turkish women. Again I regretfully demurred.

After several such visits, occasionally buying smaller items, the dealer was amused and agreed: I could have the dress for $10. Sold! He threw in a lovely silver-threaded man’s fez as a gift.

When I returned to my parents’ home in Florida, the local newspaper did a feature story about my Peace Corps adventures, showing me in the dress (now with a satin lining) but getting nearly everything wrong about Turkey and my views of it. Still, I had decided to work for a newspaper myself—journalism’s global variety of subjects would again let me avoid choosing among them.

Reporting jobs were rare for women in 1967, but in New York I was hired by United Press International—and sent to South Dakota. There I wore the dress to general admiration. In subsequent years it went to parties wherever I lived.

Journalism suited me. For a reporter, being an adaptable chameleon and interested in everything is a feature, not a bug. And in a final irony, I eventually became The Washington Post’s first woman foreign correspondent—in South America. And it wasn’t dull at all.