I was probably one of the few Peace Corps Volunteers who ever requested Chad, not knowing it was considered a hardship post. Although I had lived in North Africa, had a Master’s degree in African Studies and traveled extensively on the continent, I knew little about Chad. I just knew I wanted to go there.

When I arrived, the nation had been independent from France for only eight years, and the French influence was still very strong. It was a country cobbled together from a desert in the north, a savannah in the south, the Sahel in between and a mixture of more than two hundred linguistic and ethnic groups. I was stationed in the capital, Fort Lamy (now called N’djamena), a place that was a mélange of indigenous groups, French bureaucrats and soldiers, expats and aid workers from various countries. We also saw the occasional half-mad individuals who had crossed the Sahara, some on bicycles.

The French doctor who directed the World Health Organization Well Baby Clinics where I worked felt that Americans were intruders, but my Chadian counterparts were welcoming and supportive. The clinics were stationed in the outskirts of town where newcomers from the countryside built scattered adobe houses. We trained social work and nursing students to weigh babies and to discuss the importance of breast feeding (as opposed to using powdered milk) with mothers. We trained them in procedures to help prevent diarrhea and infant mortality. We made home visits to discuss the importance of improving sanitation by digging latrines and wells. Often our work was interrupted because of muddy roads or the breakdown of the only jeep that could bring students and staff to the clinics.

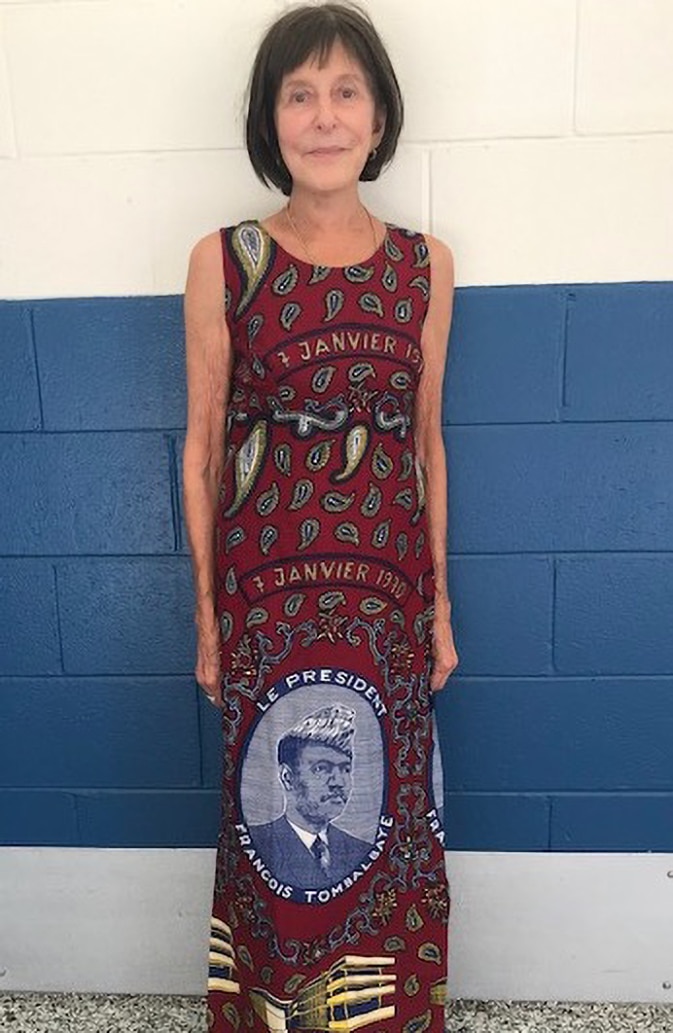

Like my friends and counterparts, I had a dress made for the four-day celebration of Chadian independence. My dress said Janvier 1970 on the top and featured photos of President Tombalbaye on the skirt. a new bridge and an unnamed building on the hem. That same bridge led to my arrest when another Volunteer and I arrived in the southern town of Fort Archambault. That day the Vice President of Germany was visiting to survey the progress on the German-funded bridge. We were suspected of being spies there to blow up the bridge. As soon as we convinced the police that we were American PCVs, we were released.

Independence formally happened in August but was not celebrated until the following January. Perhaps the summer rainy season would have made the celebrations difficult, especially in the south. Throughout December, people practiced marching to American, English and French music. I was startled to hear “Yippie-ay-oh” and “Yippie-ay-eh” on some occasions.

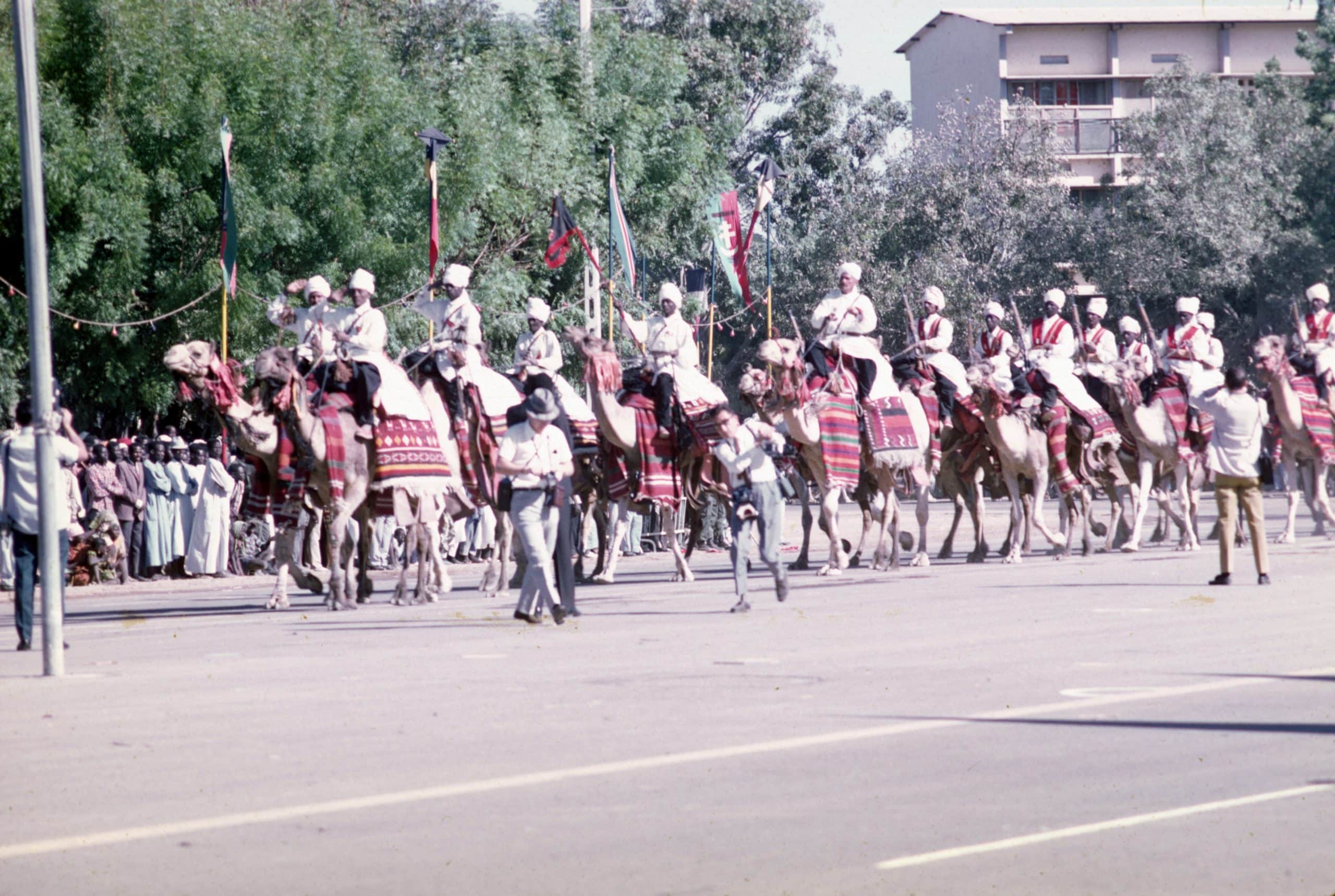

When the parade finally happened in January, it lasted for four hours, and it seemed like the entire population of Ft. Lamy participated. The Chadian national anthem, “La Tchadienne”, was played by a marching band. Members of each political party, schoolchildren, patrons of the local bar, airline personnel, and the richest man in town – each of them sponsored floats. People who worked in electrical firms marched with lightbulbs attached to their heads. Most everyone wore clothing bearing the words “Long Live Tombalbaye and Mobutu,” the presidents of Chad and the Central African Republic (CAR) respectively. Some marchers cut out the picture of Mobutu because of a recent dispute between the two countries.

Signs saying, “Down with Colonialism” and, “Lale (Hello) Mobutu” were in the parade, followed by chiefs from the north with umbrellas held over their heads. The chiefs rode on horses resplendent in tassels, tin and furs. The Chadian Camel Corps swayed by, followed by oil trucks. Finally, Chadian dancers—scantily clad young women from Baibakou, men in animal skins with their faces painted ashen white, and Arab women whirling in their dresses. The grand finale, of course, included tanks from the Chadian army.

Wearing my dress in this celebration made me feel the pride and freedom shared by the people of Chad. Despite the difficulties of Peace Corps service, it was (as advertised) “The Toughest Job I Would Ever Love.” I had a feeling of utter peace as I walked through Fort Lamy thinking about the work I was doing to help develop this newly independent nation.