“The main thing is to listen to people before you start a program, and then to work at their level.”

These words from my wife Anne were quoted in a Milwaukee newspaper. They described her work after completing Peace Corps service, as she worked in Milwaukee with inner city youth and mothers on welfare. She was applying lessons we both had learned in the Chuuk Lagoon of Micronesia. For Anne, the inner city seemed like just another island. We had been married only four weeks when we entered Peace Corps training in Key West, Florida. We received intensive training in the Chuukese language and learned methods for teaching ESL. When we arrived in Micronesia, we were assigned to teach at Chuuk High School. Many of our students came from outer islands and had limited transportation services. They couldn’t return home during the school year, thus we were teaching in a boarding school The principal knew I had a B.A. in Industrial Arts Education and wanted me to teach outboard motor mechanics. Water travel is central to Micronesian lifestyle, and a working engine can be both a status symbol and a lifesaver. I was also assigned to teach mathematics. Anne taught girls sewing, food preparation, nutrition, sanitation, and how to keep their families healthy.

We brought back a few objects to remind us of island life. One which closely reflected Micronesian culture was a student-crafted bird image made from a coconut shell. A common greeting in Chuukese is literally translated as “there is food” rather than “hello.” Such was the significance of the coconut in daily life. With machete in hand, your Chuukese friend might climb a nearby palm to bring down a ripe coconut. You drink the milk. You eat the chopped meat. You take some of the fiber with you to use in place of toilet paper. Everywhere you go—from your sleeping mat to thatched roofs, woven baskets, or the rope in the dugout that transports you to another island—coconut goes with you. Dried coconut (called copra) is Micronesia’s most important agricultural export. The bird represented in the student’s gift also reminded us that Chuukese people can navigate open oceans in their sailing canoes without GPS. In addition to “reading” the waves and stars, they observe nearby birds to find their bearings.

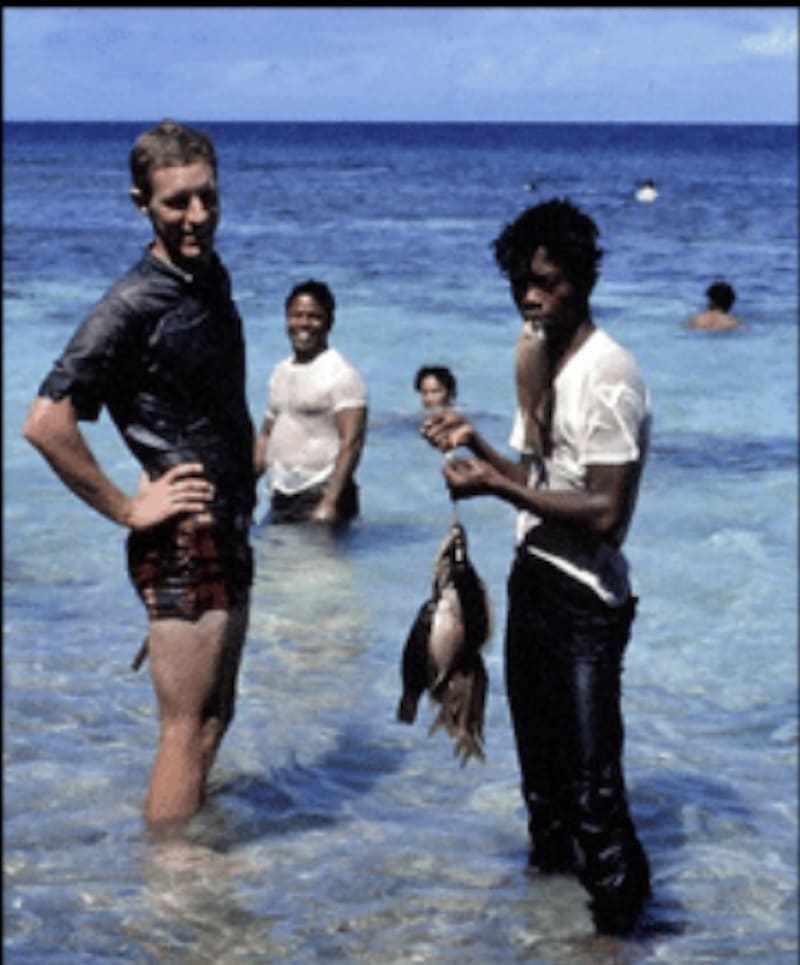

On Saturdays we often took our boarding students to visit uninhabited “picnic islands” where they could release pent-up energy by eating prepared meals, spearfishing, and playing games. The girls went separately with Anne to swim in the lagoon. I watched the boys dive and bring back fish with nothing more than handmade spears that were propelled by rubber from inner tubes. Their skills and confidence amazed us in so any ways.

Six days after returning from Micronesia, I was drafted and sent to fight in Vietnam. Both were life-changing experiences, but of the two, I would say that the Peace Corps changed me more profoundly. As Anne said to the newspaper reporter, “We listened in Chuuk and learned how to work at their level.” What we learned in the Peace Corps has served us well throughout our lives.