In my coastal community of Albornos and throughout rural Colombia, a machete is a universal tool. You could use it for just about everything – hammering nails, cutting wood, chopping vegetables, or gutting fish. I carried one by my side in a leather sheath almost every day.

As a community development volunteer, I spent my first few months getting to know the people and understanding their needs. Among other projects, I helped them build a school, and I taught Spanish literacy while improving my own Spanish.

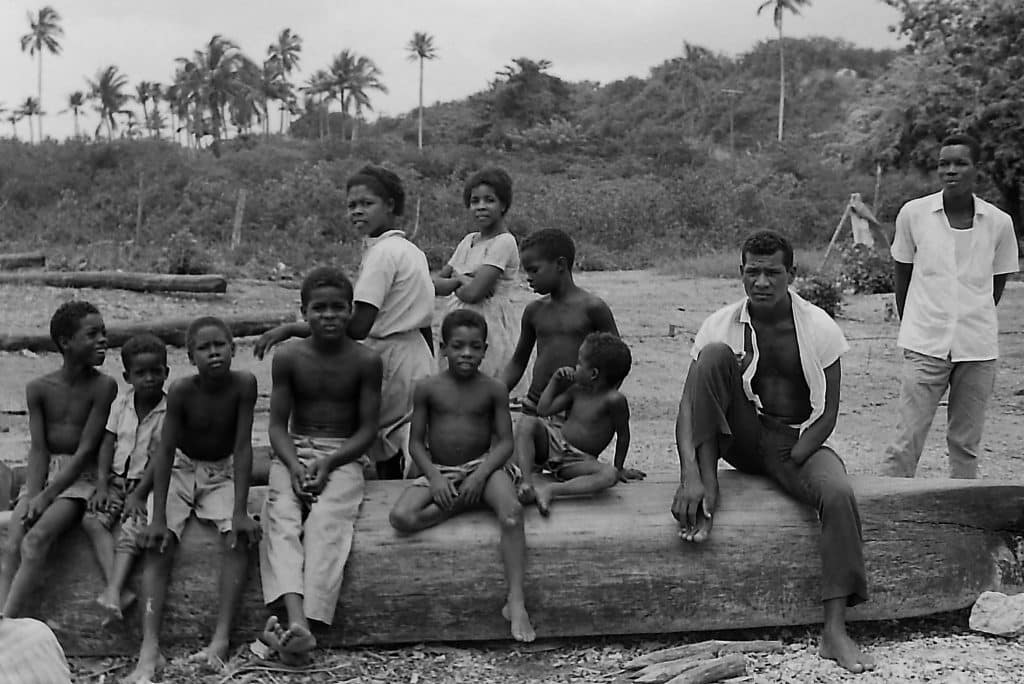

Albornos was one of several “invasion” barrios where Afro-Colombians had migrated from rural areas to be near Cartagena in hopes of a better life. Since Albornos was on the bay, many became fishermen.

Some worked in construction where they could get dynamite. Unfortunately, they had learned an explosion in the water would kill schools of snook and tarpon. It worked, but they were depleting the fish population and destroying the habitat. Dynamite fishing was also risky. Unreliable fuses would burn too quickly and the dynamite could explode in one’s hand, rendering the fishermen as mochos – one-handed.

I’ll never get over paddling in dugout canoes with mochos who had mastered paddling with one hand. They would find a school of fish, stop paddling, place a match in their teeth, grab a stick of dynamite, hold the strike pad in the same hand, strike the match, light the fuse, and throw the dynamite into the water – risking the loss of the remaining hand.

There had to be a better way. I knew nothing about the fishing business, but I read about fishing cooperatives and learned that the agricultural bank would make loans to registered coops. With a loan, they could purchase motors and nets to provide a viable alternative to dynamite. The project succeeded. The fishermen of five villages united to incorporate and get loans to buy nets and small 4-horsepower British Seagull motors for their dugout canoes. They could get to the fish more quickly and use nets to catch fish without blowing off their hands. Then they would haul in their catch and go to work with their machetes.

My favorite among the villages was Baru at the tip of a peninsula, where the patriarch was called El Viejo, the Old Man. He became my friend and mentor and one of the most wonderful people I’ve ever known. He was central to introducing the Cooperativa de Pescado concept.

One very hot day my local counterpart and I drove a borrowed jeep over a crude trail to Baru to take a borrowed projector and generator to show a U.S. Information Service film on how coops work. However, the trail turned into a soft beach about 15 kilometers from the village, and we were stuck in the sand. We left the vehicle and equipment and started walking. Near Baru, I was dying of thirst and spotted a beautiful mango tree filled with red ripe mangos. I grabbed one after another and bit into the skin to squeeze the juice into my mouth.

By the time we reached El Viejo’s house, my face and throat started swelling. I could hardly breathe, and I seriously feared suffocation. I recovered the next day and learned that I was allergic to the toxins in the mango skin. As much as I love the taste, I have avoided anything with mango ever since.

El Viejo mobilized a group to hike to the Jeep and carry the heavy equipment back to the village. The village loved the film, and the next day they accompanied us back to the jeep and dug it out of the sand so we could return the jeep, film, and equipment.

Eventually, dynamite fishing was reduced, and the coral began to thrive. attracting thousands of tourists who can drive to Baru on an improved road. They occupy new luxury hotels and scuba dive among the reefs, enjoying the fish who live there.