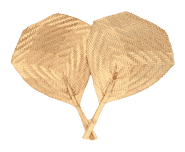

Presented by Museum of the Peace Corps Experience and American University Museum

c. 1979

Lower River Division, The Gambia

Grass, 18 x 12 1/4 in. each

Collection, Museum of the Peace Corps Experience

Gift of Paul Jurmo, The Gambia, Pakalinding 1976–79

My education in mosquito affairs began on the first night in my village of Pakalinding. I had arrived after a 100-mile ride from the capital with my furniture in the back of a truck. Sweaty and tired at the end of the day, I finally climbed onto my foam mattress, which was covered with a newly purchased mosquito net.

The next morning I awoke to find a half dozen mosquitoes on the inside of my net trying to escape through the fabric. I slapped them between my hands only to discover that they were engorged with my blood. My neighbors later explained that the modern type of mosquito net I’d bought in the city had gaps just large enough to let hungry mosquitoes in—but when the insects were engorged, the holes were too small for them to escape. For their own nets, villagers used a much more densely woven cheesecloth-type fabric. Needless to say, I bought a more tightly woven net as soon as possible.

Thus began a three-year relationship with suusuulaa (“mosquito” in Mandinka)—and learning how to deal with her. Peace Corps volunteers took a dose of chloroquine phosphate once a week as a prophylactic against malaria. Without this medicine, we would have suffered from headaches, fever, chills, nausea, diarrhea, or possibly death—symptoms all too common among our Gambian neighbors.

As a young volunteer, I lived with a large Gambian family. Each night they welcomed me to sit outside in the dark with my landlord and other adult male family members and friends. We would chat, pray, and share a pot of sugary tea. Frequently a small boy was assigned to fan us gentlemen to cool us and keep the mosquitoes away.

Such fans were ubiquitous tools in Gambian households. Village women wove them from local grasses using techniques handed down over generations, supplying their families and sometimes selling them in the market for extra income. They were multipurpose—used to shoo insects from people and food, to lessen the effects of energy-sapping heat, and to serve as a bellows to start the cooking fire. During intense daylight hours a fan could also function as a sun visor.

Forty years later, I appreciate that these simple, everyday devices were artistic, health protecting, environmentally sustainable, income generating, and culturally rooted. They were beautiful artifacts of a rich, communal way of life and represented many of the best qualities of the Gambian people.

The Committee for a Museum of the Peace Corps Experience is a 501(c)(3) private nonprofit organization. Tax ID: EIN # 93-1289853

The Museum is not affiliated with the U.S. Peace Corps and not acting on behalf of the U.S. Peace Corps.

Museum of the Peace Corps Experience © 2024. All Rights Reserved.