Presented by Museum of the Peace Corps Experience and American University Museum

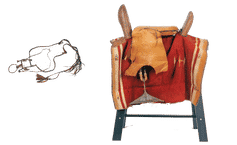

Bit and harness (left)

Kanembu people, mid-twentieth century

Lake Chad Region, Chad

Iron, leather, dimensions variable

Collection, Museum of the Peace Corps Experience

Gift of John Hutchison, Chad, Doum Doum 1966–68

Saddle, blanket, pillow, stirrups, and straps (right)

Kanembu people, mid-twentieth century

Lake Chad Region, Chad

Wool, leather, cotton cushion pad, iron, dimensions variable

Collection, Museum of the Peace Corps Experience

Gift of John Hutchison, Chad, Doum Doum 1966–68

I was introduced to my horse, Balzac, upon my arrival in Doum Doum.

Doum Doum was a village of 200 where I was assigned as part of the Peace Corps’ first project in the Republic of Chad. I was one of a group of about a dozen generalists who were expected to turn the region into the breadbasket of Equatorial Africa. Balzac was provided to me by the government of Chad for transportation during this project.

Several months later, in the Massakori market, I purchased a camel named Gunther for the equivalent of $40. I parked Gunther next to Balzac in my zanna-mat courtyard. I also became the owner of two oxen and two $5 donkeys who carried water from a well to my house three kilometers away.

The Chadian government, in collaboration with the French organization SEMABLE, wanted to grow wheat in the reclaimed Lake Chad bottomland to supply the national flour mill in Fort Lamy. We were challenged to introduce the oxen-drawn plow into the agriculture here. Even though Monsieur Grimal, the director of SEMABLE, proudly referred to our group as agents de modernisation, we did not succeed in transforming the agriculture of the region. (Lake Chad has diminished in size by 90 percent since we were there in the 1960s due to climate change, population growth, and unplanned irrigation far beyond the lake’s shore.)

My neighbor El-Hadj Mbodou Wuli became my super-farmer colleague. He gave me part of his farm to work on, installing a small well with a water-lifting chadouf apparatus. He and his family became my family. When it was time to do a plowing demonstration in a neighboring village, El-Hadj’s family would ride on our two oxen, I rode on Balzac, and El-Hadj would walk alongside all of us. My Chadean government counterpart, Mohamed Djibro, would ride my camel, Gunther, along with the plow that we used for our demonstrations. We arrived at each village appearing to the residents as a veritable traveling circus.

El-Hadj was also my patient tutor in the Kanembu language. With him I learned of the wisdom and humor that permeate their language and culture.

After my service I became a professor of African languages and linguistics at Boston University. I often think of the curious fact that my academic career in and about Africa began with my four-footed housemates Balzac and Gunther.

The Committee for a Museum of the Peace Corps Experience is a 501(c)(3) private nonprofit organization. Tax ID: EIN # 93-1289853

The Museum is not affiliated with the U.S. Peace Corps and not acting on behalf of the U.S. Peace Corps.

Museum of the Peace Corps Experience © 2024. All Rights Reserved.