In January 1969, I arrived at my site about 40 miles west of Kisumu in Nyanza Province, Kenya. My assignment was to teach at Nyamira Girls Secondary, a school founded in the harambee tradition of community cooperation. In Swahili, harambee means “all pull together” to meet a local need. Harambee schools like Nyamira have been crucial in the growth of secondary education for the students whose test scores precluded admission to Kenya’s government schools.

Nyamira, community-managed with shaky finances, was next door to the family compound of the school’s founder, Oginga Odinga, then leader of Kenya’s opposition party and former vice president under Jomo Kenyatta. A few days after I came, Odinga hosted a welcome party for me, spilling a little beer on the floor of my house as a libation for the ancestors, whose blessings he sought.

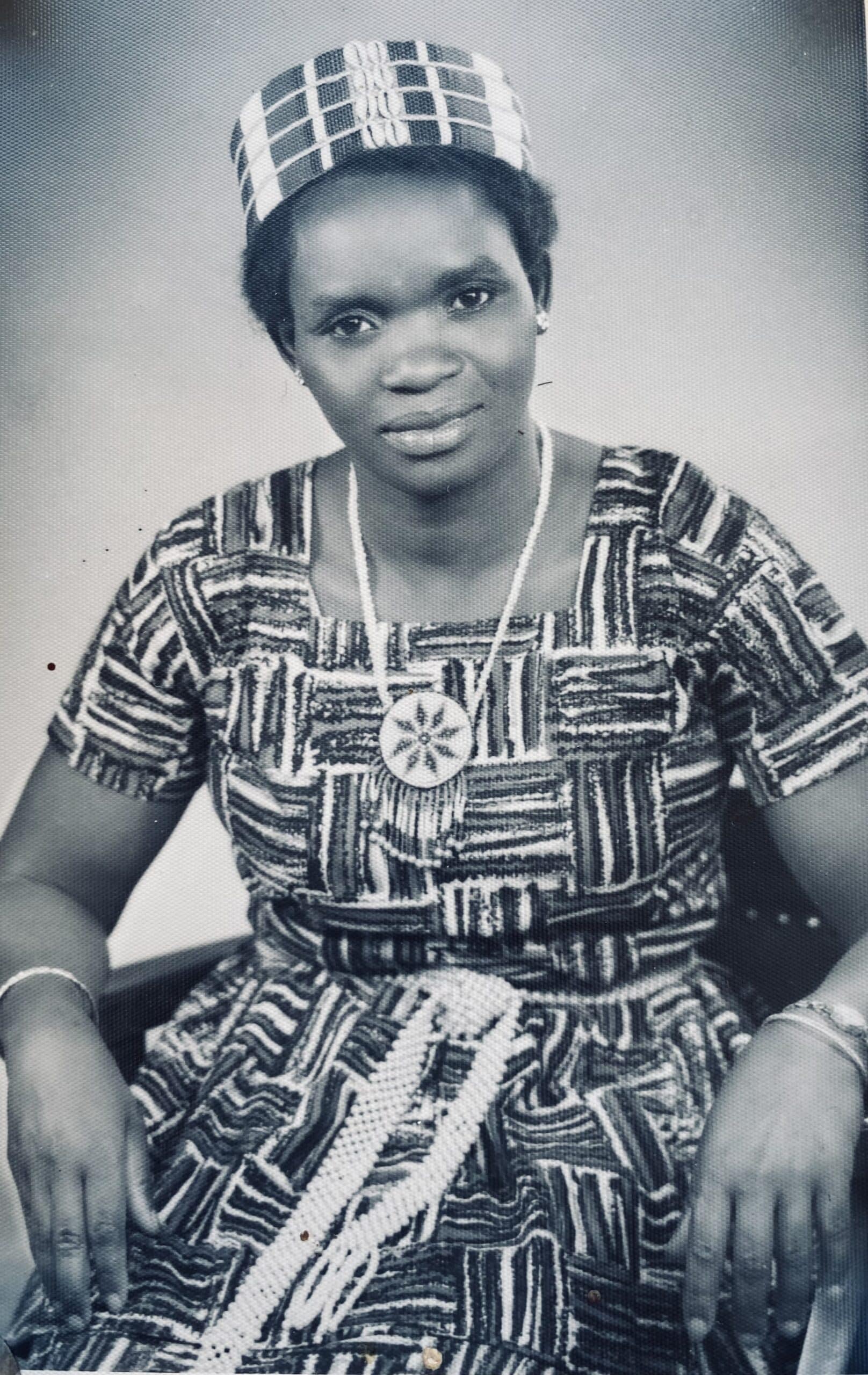

My students were captivating. Day after day, their skills, strength, humor, warmth and love astounded me. During those first few months, we were happy getting to know each other at the remote site. With only two other teachers on staff, I had to teach history and science as well as English. We produced plays and publications using our mimeograph machine. We started a track team that competed successfully against government schools. My students danced in the dormitory to popular Luo songs of the era. When they sang religious and traditional music, they harmonized so beautifully that it sent chills down my spine. Those were the days when Nyamira seemed almost idyllic.

But then trouble arose in the form of a corrupt and abusive headmaster who stole school funds and impregnated one of the students. He was arrested, tried, and imprisoned. In the meantime, the community asked me to head the school. The offer stymied me. Peace Corps staff advised against it. But the community persisted. Shaken by the perfidy of the headmaster, the community had evidently decided to put their trust in a young American teacher who seemed singularly devoted to educating their girls. They assured me that they would support my work and that my service would help restore the school’s reputation, which was sullied by the headmaster scandal. At last, I agreed, reasoning that I could help fill the urgent need on a temporary basis.

For the next 17 months, I served as headmistress, working 10-hour days to manage school affairs while continuing to teach. I no longer had time for extracurricular activities, but I tried to keep the school on an even keel through many challenges. My cherished dream was for the girls to pass their junior secondary examinations so that they could continue their education, since Nyamira Secondary had only grades nine and ten at the time. We worked hard to achieve that dream, and a few did manage to get into government schools. After about a year, the Minister of Education visited the school and set in motion the process to designate Nyamira as a government school with steady funding thus ensured.

I continued teaching and managing admissions, scheduling, purchasing, and other school business. One day, the man who supplied us with cabbages asked whether I had African blood. Surprised and somewhat amused, I replied, “I don’t think so! Why do you ask?” He said that people in the community had heard that African Americans could be light skinned. They thought that an African heritage might explain why I cared so much for the students.

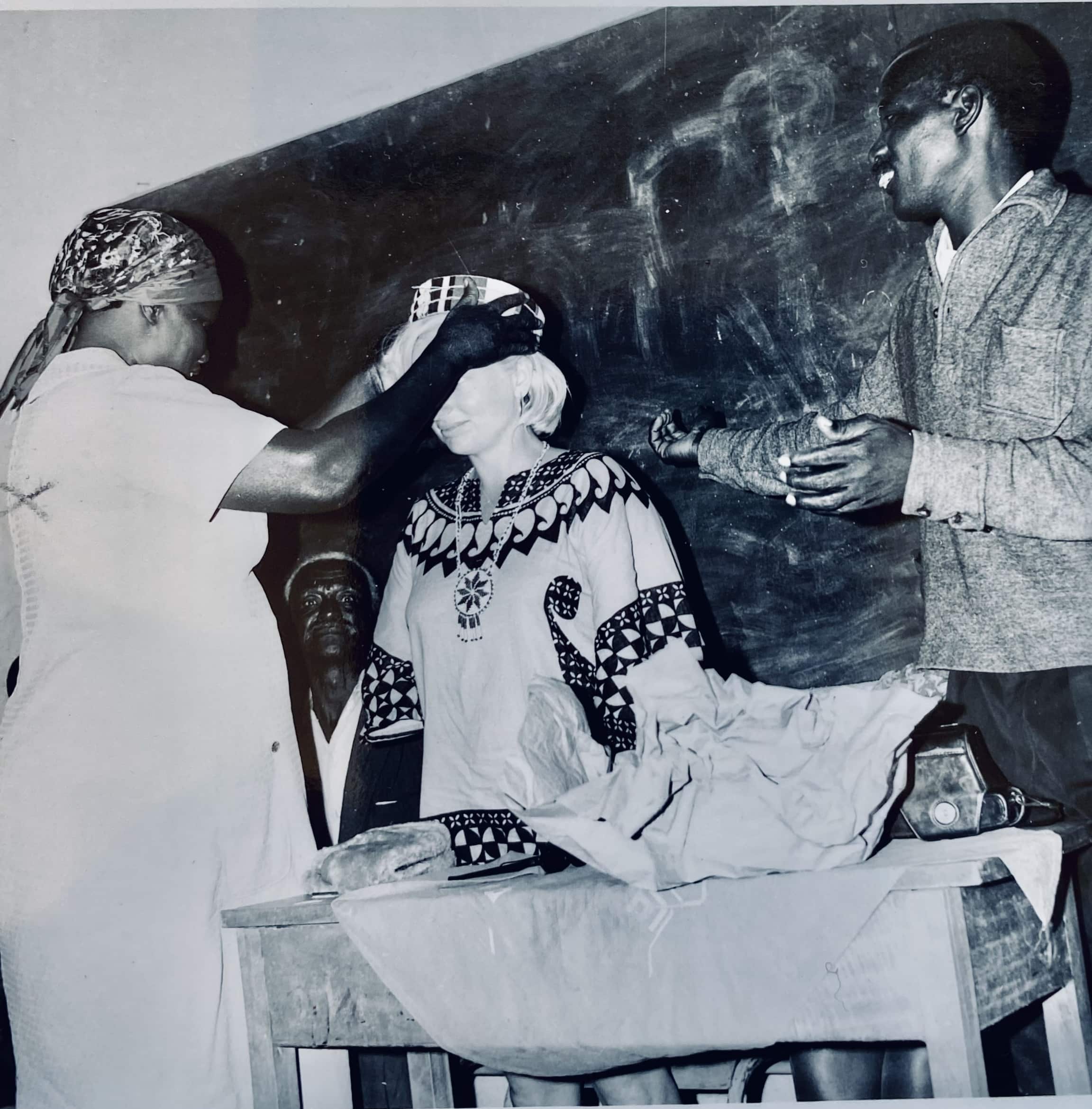

When it came time to leave my site, the community gathered and gave farewell speeches. Some of us wept. A newspaper reporter covered the event for the Daily Nation and the Standard, Kenya’s two newspapers at the time. The Standard ran a photo showing a local leader placing on my head a beaded headdress–the traditional adornment worn by Luo leaders. I knew that this was the community’s way of thanking me for my work and recognizing that a loving commitment to young students does not necessarily mean shared ancestry. Yet in retrospect, I wonder whether some Luo ancestors actually were involved in overseeing my sojourn at Nyamira, because my years there seemed remarkably blessed.