When I came home, she was there – waiting for me. If I let her, she would nibble on my neck while humming her little tune. They called her Suusuulaa.

I am referring, of course, to the Anopheles (Greek for “useless”) mosquito. I became intimately acquainted with this creature in The Gambia, where I spent three years as a Peace Corps volunteer. Translated from Mandinka, suusuulaa means “sucker” and that’s what the females do whenever they have the chance. (Males suck flower nectar rather than blood. They live only half as long.)

My education in mosquito affairs began on the first night in my village of Pakalinding. I had arrived after a 100-mile ride from the capital with my furniture in the back of a truck. At the end of the day, I finally climbed, sweaty and tired, onto my foam mattress covered with a newly-purchased mosquito net.

The next morning, I awoke to find a half dozen mosquitoes on the inside of my net, trying to escape through the fabric. I slapped them between my hands, only to discover that they were engorged with my blood. My neighbors later explained that the modern type of mosquito net I’d bought in the city had gaps just large enough to let hungry mosquitoes in—but when the mosquitos were engorged, the holes were too small for them to escape. Needless to say, I bought a new, more-tightly-woven net as soon as possible. For their own nets, villagers used a much more densely woven cheesecloth-type fabric.

Thus began a three-year relationship with Suusuulaa and learning how to deal with her. I was concerned about more than the itching or possibility of infection from too much scratching. There was the risk of coming down with malaria, which has one of its deadliest strains in in The Gambia. European colonists found it hard to survive in this part of West Africa. All Peace Corps Volunteers took a dose of chloroquine phosphate once a week as a prophylactic. Without this medicine, we would have suffered from headaches, fever, chills, nausea and diarrhea—symptoms all too common among our Gambian neighbors.

The mosquitoes hung around the exterior wall of my mud-block house, following the course of the sun. To stay cool, they swarmed in little groups on the shady side of the house. I was able tell the hour of the day by observing the location of the mosquitoes. They were a living sundial.

Despite the heat, I needed to wear socks, shoes, long pants, and a hat after sundown. Several strategically-placed splashes of repellent also reduced the likelihood of getting eaten by mosquitoes during the night. The insects had apparently evolved with an awareness that ankles are hard for humans to reach with their hands. Peace Corps Volunteers were notorious for the scabs and infections on their ankles.

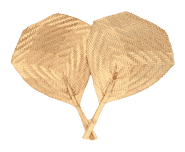

Which brings me to the fan which I have donated to the Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. As a young Volunteer I lived with a large Gambian family. Each night they welcomed me to sit outside in the dark with my landlord and other adult male family members and friends. We would chat, pray, and share a pot of sugary tea. Frequently, a small boy was assigned to fan us gentlemen, to cool us and keep the mosquitoes away.

Such fans were ubiquitous tools in Gambian households. They were used to shoo insects from people and food, to lessen the effects of energy-sapping heat, and to serve as a bellows to start the cooking fire. Before the sun set, a fan could function as a sun visor. These multi-purpose tools were woven by local women from local grasses, using techniques handed down over generations.

These fans were simple, yet they represented many of the best qualities of the Gambian people. Forty- years later, I appreciate that these everyday fans were artistic, health-protecting, environmentally- sustainable, income-generating, culturally rooted objects. They were a tool that captured a communal way of life.