While the Vietnam War was foremost in my mind as a recent high school graduate, the summer of 1969 saw another conflict, the so-called “Soccer War” between El Salvador and Honduras. A decade later, as a Peace Corps Volunteer in El Salvador, I heard about this “100 Hour War” for the first time from my landlady in San Salvador.

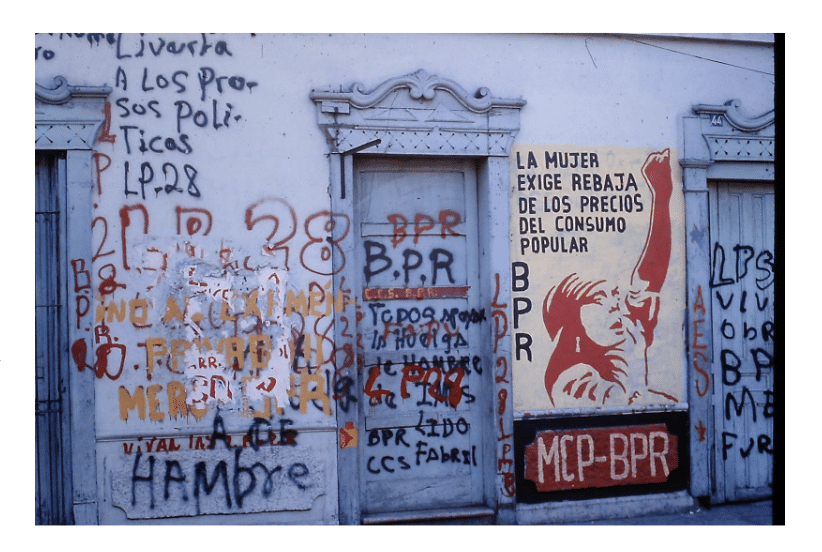

1979 was a volatile year of civil strife in the capital city—population 680,000. Political graffiti covered the walls of the business district and streets were often filled with protesters demanding social reform and better living conditions.

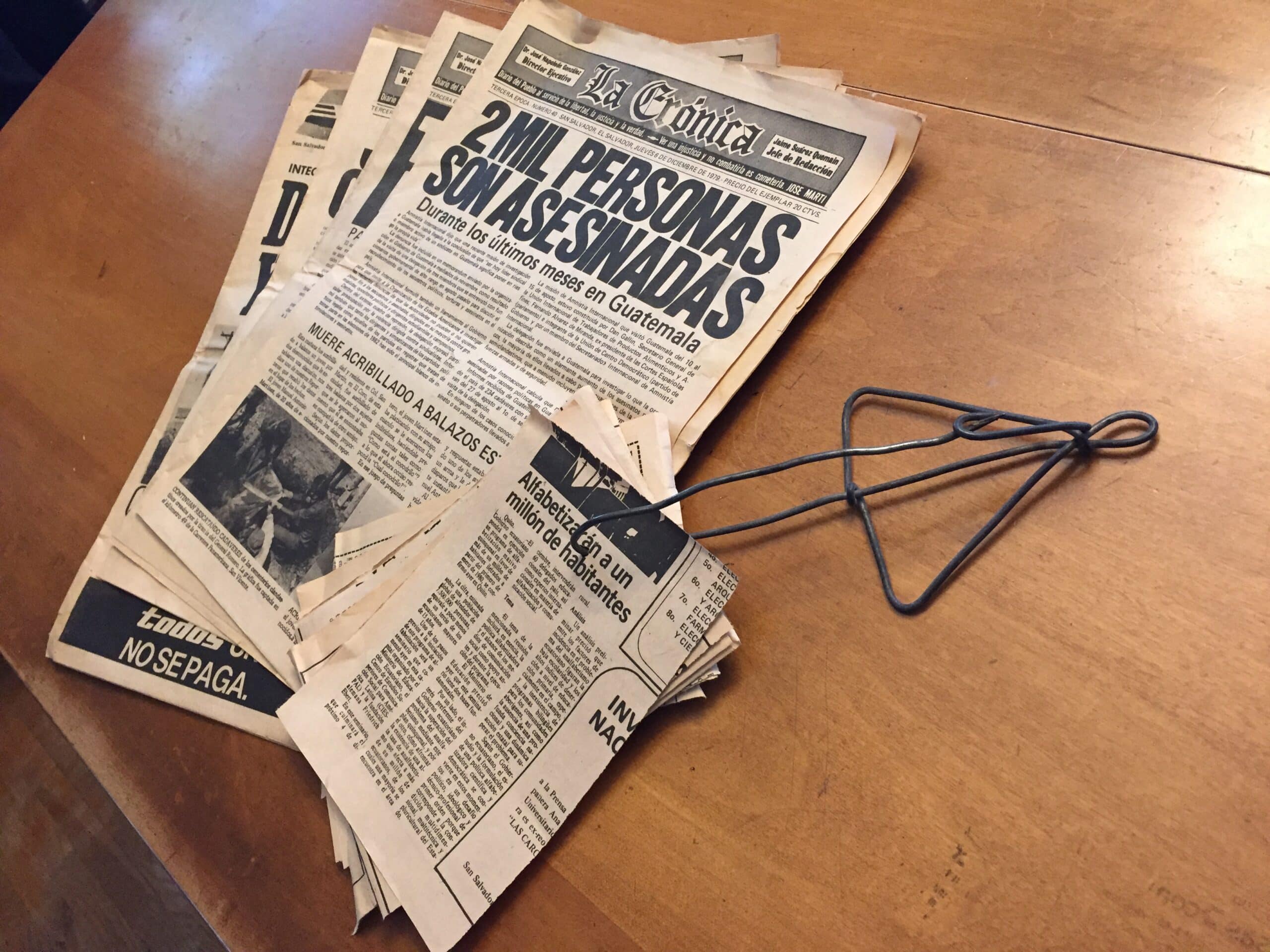

Estado de sitio, granting the government the right to instate a military curfew, was declared—no outdoor movement from 10 pm until 5 am the next morning. Newspaper headlines announced the latest numbers of desaparecidos (the disappeared) and ametrallados (the dead by gunfire). Right wing vigilantes were spoken of in whispered asides whenever national politics were discussed.

Peace Corps volunteers were called in from the countryside to find temporary quarters in the city for quick mobilization should things worsen. I found a vacancy in the home of “La Señora” not far from downtown. She showed me a tidy second floor room with a high ceiling, and tall shuttered windows. In my journal I wrote:

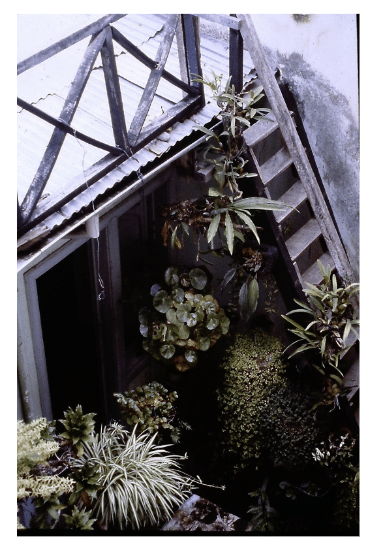

I like the view—rooftop and 2 large, tall, conical pine trees framed in the window. Below is the courtyard with plants in every corner and overflowing to the center. The wash is done just outside the window and drying clothes are always fluttering in the wind or plastered flat and rippled on the galvanized steel roof.

And there was a bullet hole.

Pointing to an ornate, full-length mirror, La Señora recounted that in the month of July, ten years earlier, a prop plane from Honduras flew over the city and fired small caliber weapons down upon the houses. One bala (bullet) came through the window and lodged in the mirror frame. Luckily no one was standing there at the time. She went on to explain that the short-lived conflict between the two countries began over land disputes and a series of belligerent soccer games. It lasted just four days with few casualties.

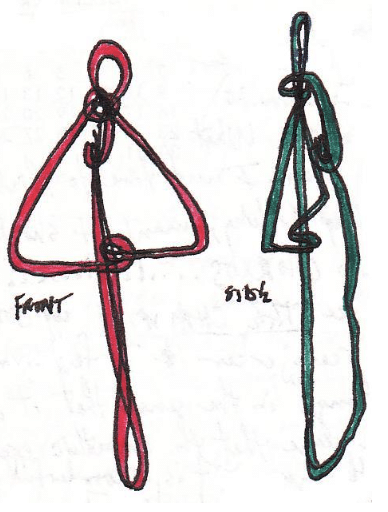

A more down to earth concern than bullets from the sky was the plumbing. I was warned not to flush any paper down the toilet—the old plumbing couldn’t handle it and roll tissue was just too expensive to waste. Instead, I was to use some spindled newspaper squares on a wire toilet paper hanger in the bathroom and dispose of them in the waste basket under the sink. Weeks later, arriving home from my work at the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, I witnessed the incommodious reason for this advice. As I passed by the open door of the shower room I caught the indelible image of La Señora, her daughter, and the maid who was posed above the floor drain while bearing down on a rubber plunger. The toilet had plugged up!

Just before Christmas it was decided that all volunteers were to be evacuated. My host family prepared a lavish going away meal. Following dessert and coffee, La Señora inquired if there was anything I would like to take with me as a souvenir of my time with them. After a moment’s pause I sheepishly responded, “Well…I don’t wish to offend but what I would really like to have is the wire gancho (wire hanger) upstairs in the bathroom.” After many smiles all around I was sent forthwith to retrieve said toilet paper dispenser.

Forty years later, during the early months of the Covid pandemic when toilet paper could not be found anywhere in stock across the United States, I was poignantly reminded of this practical solution for personal hygiene from my Peace Corps days in El Salvador.