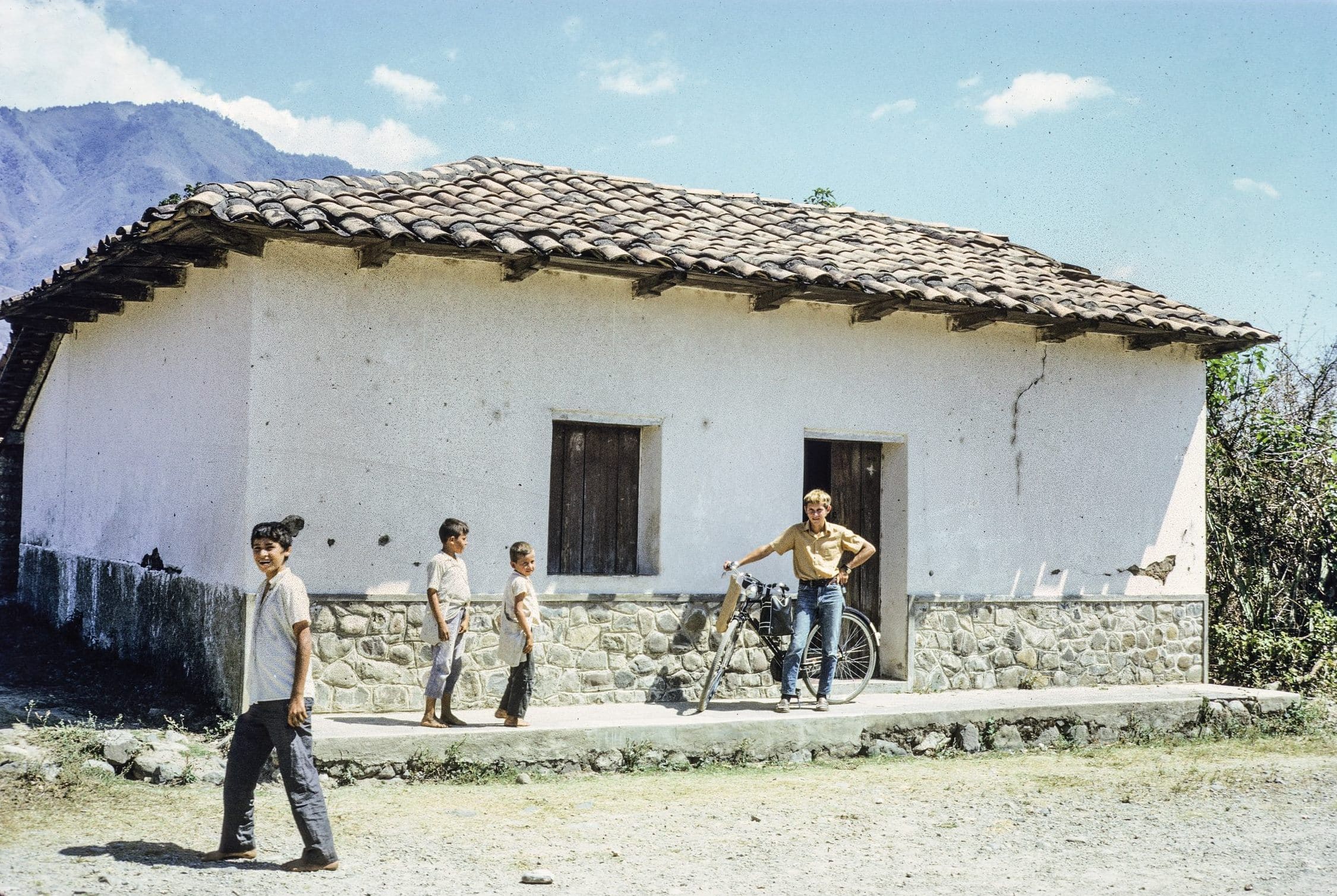

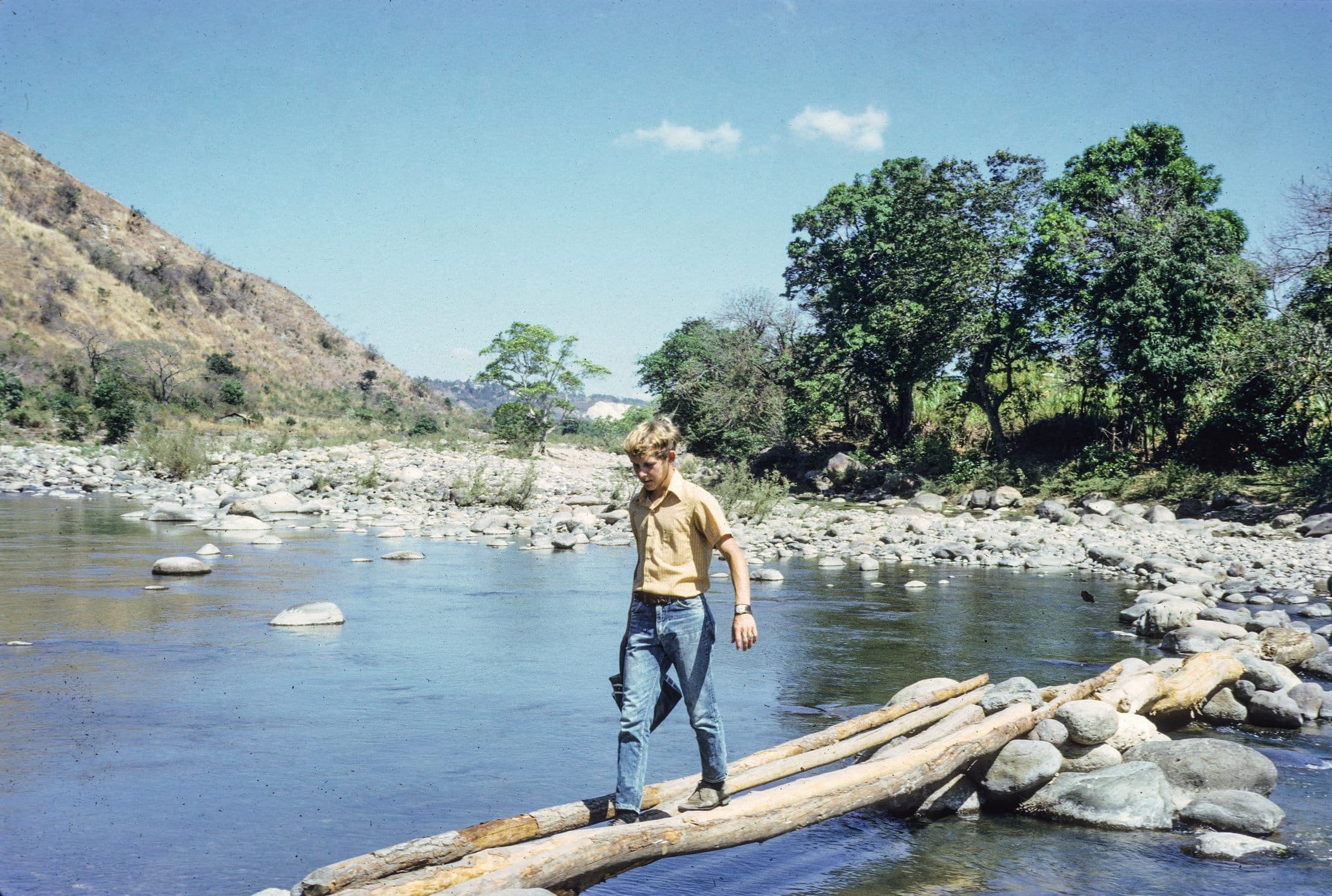

A young woman approached me one afternoon in our small farming town in the mountains just south of the Guatemalan border. We had not spoken much before that day, but 50 years later I vividly remember our conversation.

She asked if I would take a picture of her two-year-old daughter. I didn’t know of anyone else in Antigua Ocotepeque who owned a camera, and apparently, she didn’t either.

So I readily agreed.

She said she first wanted to go home and get her daughter dressed up for the occasion and she would let me know when they were ready. It didn’t take her very long. When I arrived she led me through her house and into their garden behind the house to meet the little girl.

Obviously this two-year-old was her little jewel, the light of her life, as she had spared nothing to make her small daughter pretty for the camera. She must have labored daily to keep diapers and dresses clean. I took my Kodak Instamatic X-35 out of my bag and shot a couple photographs to make sure that I got a good one.

A week or so later when I received the prints, I heard her child had died.

The next day I watched the funeral as they carried her tiny wooden coffin past my house to the cemetery.

When the processed photos came back to me I was relieved that they were nice but I felt that I couldn’t take them to the young mother so soon after the child’s death. But I kept them with me in my shoulder bag, just in case.

A couple of days after the funeral, I saw the woman on the street. She came up to me and asked how the pictures turned out. “Here they are,” I said and handed them to her on the spot.

She looked at the photographs and then at me. I will never forget what she said with a remnant of a smile on her face but without sadness in her voice.

“Fijese que se me murió la niña.” You know that she died on me!

It was my second year working on cooperatives with farmers in Ocotepeque and I was becoming frustrated. But my petty frustrations paled in comparison with the trials of Honduran campesino families. Their corn and bean crops were threatened by poor rains when El Niño came along. The year was a very bad one for Honduras.

But the words of the young mother changed my perspective. I have never felt a more poignant moment in my life. In one phrase, she summed up the essence of the struggle for life in that poor countryside. She had just suffered the worst tragedy a parent could imagine, but she recounted it with a striking stoicism that had to have belied her true feelings. Taken aback, I offered my condolences in the best way I knew at the time, but as always, such words were inadequate.

That event, more than any other, caused me to ponder and re-evaluate everything I had come to believe about the Honduran people. Hondurans do not hide their emotions but express both sadness and elation as freely and liberally as people anywhere else in the world. Where did this stoicism come from? It wasn’t that this young mother didn’t care about that child.

It was painfully obvious to me that she loved that child deeply, and she wanted the photograph in order to remember her little girl. But in the words she spoke to me she also told me her small daughter’s death was not an extraordinary event in these people’s lives. They call their departed infants angelitos, or “little angels,” believing their innocence gives them a free ticket to heaven. Perhaps this dulls the sting of their loss.

Maybe the perceived stoicism was there because she recognized that I was different from everyone else in Ocotepeque, and maybe she thought I wouldn’t think much about a small child’s death in this little town. But I did. I still remember it vividly and to this day I think about it often.