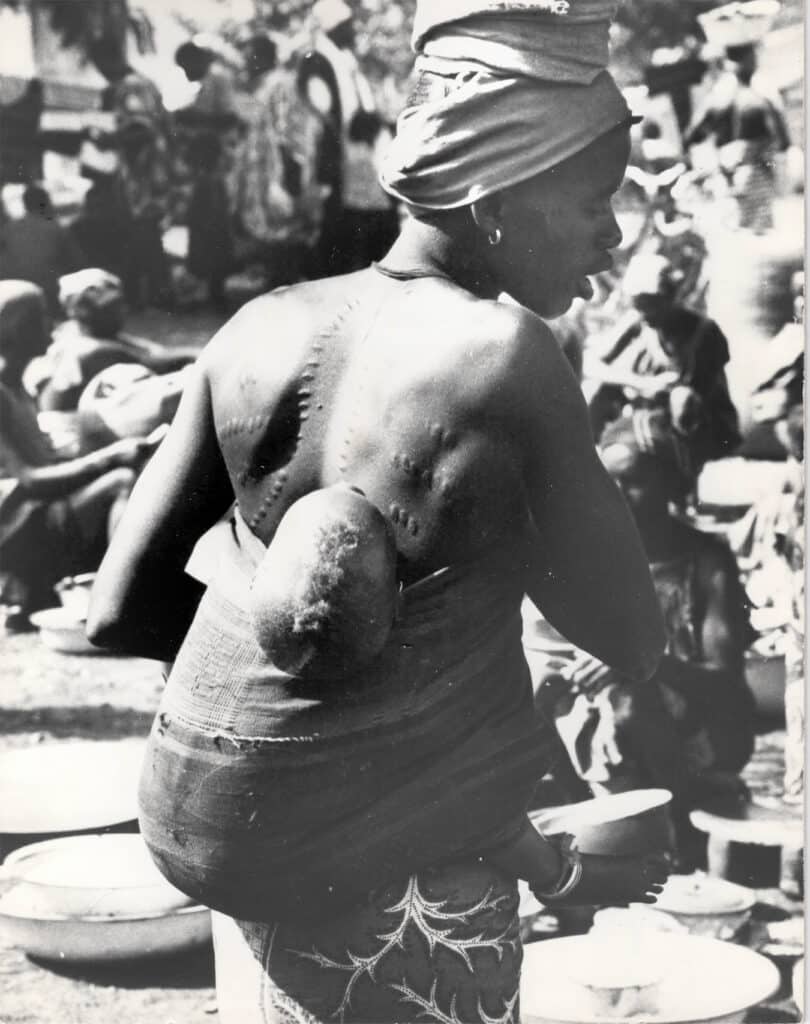

“An ni bara” she said to me in Dyula without breaking her stride. A load of firewood was on her head; a baby was held to her back by a length of cloth tucked around her breasts; her bare feet moved over the gravel trail as she hastened back from the fields. “M’ba, an ni bara,” I replied.

Being greeted with an ni bara by a woman in our village returning loaded down from the fields was the highest compliment and recognition I could have received.

An ni bara is literally “We and work.” It is the greeting when you meet someone who is working. It means, “I see that you are working,” “Thank you for your work,” “Take heart and keep going,” “You are doing a great job,” “In work we are strong.” It is spoken, almost chanted, for praise and encouragement.

For the Sénoufo with whom I lived in the village of Sirasso in the northern Côte d’Ivoire, work was a defining virtue. As a traditional agrarian people, work was not only how they survived, but also how they honored their connection with and gratitude for the spirit living in Nature. Their word for “fruit” is “tree child.” When one picks a fruit, one is actually taking the tree’s child! So one must ask permission of the tree, and thank it.

Practices like this gave their everyday work a sacred significance and is the basis of what we call “animism.” Seeing this also shook the very foundation of the consumerist sense I was used to, including the sense of entitlement to all products, natural, cultivated, or manufactured.

Sirasso was a new sous-préfecture after independence, an upcountry administrative district. Our work was to help the village infrastructure transition into a functioning seat of government. We coordinated village heads of families to build housing they could rent to civil servants who would come there to live and work. Each family group sent a helper, forming the work crew to build the new homes.

After a year in Sirasso, I had settled in pretty well, and was making a lot of friends. My closest friend had adopted me, giving me his family name, Coulibaly. This indicated that I was part of an extended family. According to custom, I was called either “older brother,” or “younger brother.”

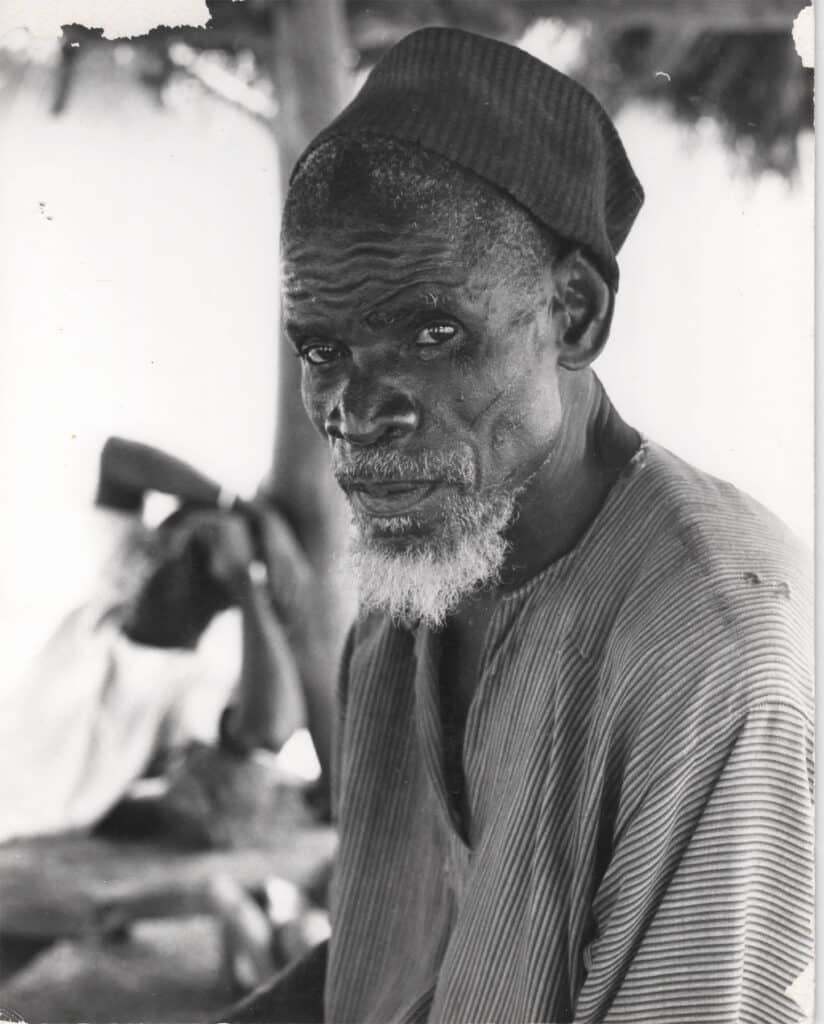

Nevertheless, some of the villagers were still not certain where I fit in the village. The elders weren’t quite sure how to treat me. Although I was a young man, I had a beard, which in their world was the mark of an elder, yet obviously I was not an elder.

Traditionally, a person’s age determined their role in society. Age marked the rights and responsibilities at each stage of life. The spiral of life unfolded in seven-year cycles, each representing a new role. Ceremonies of passage highlighted these milestones, and special celebrations were held.

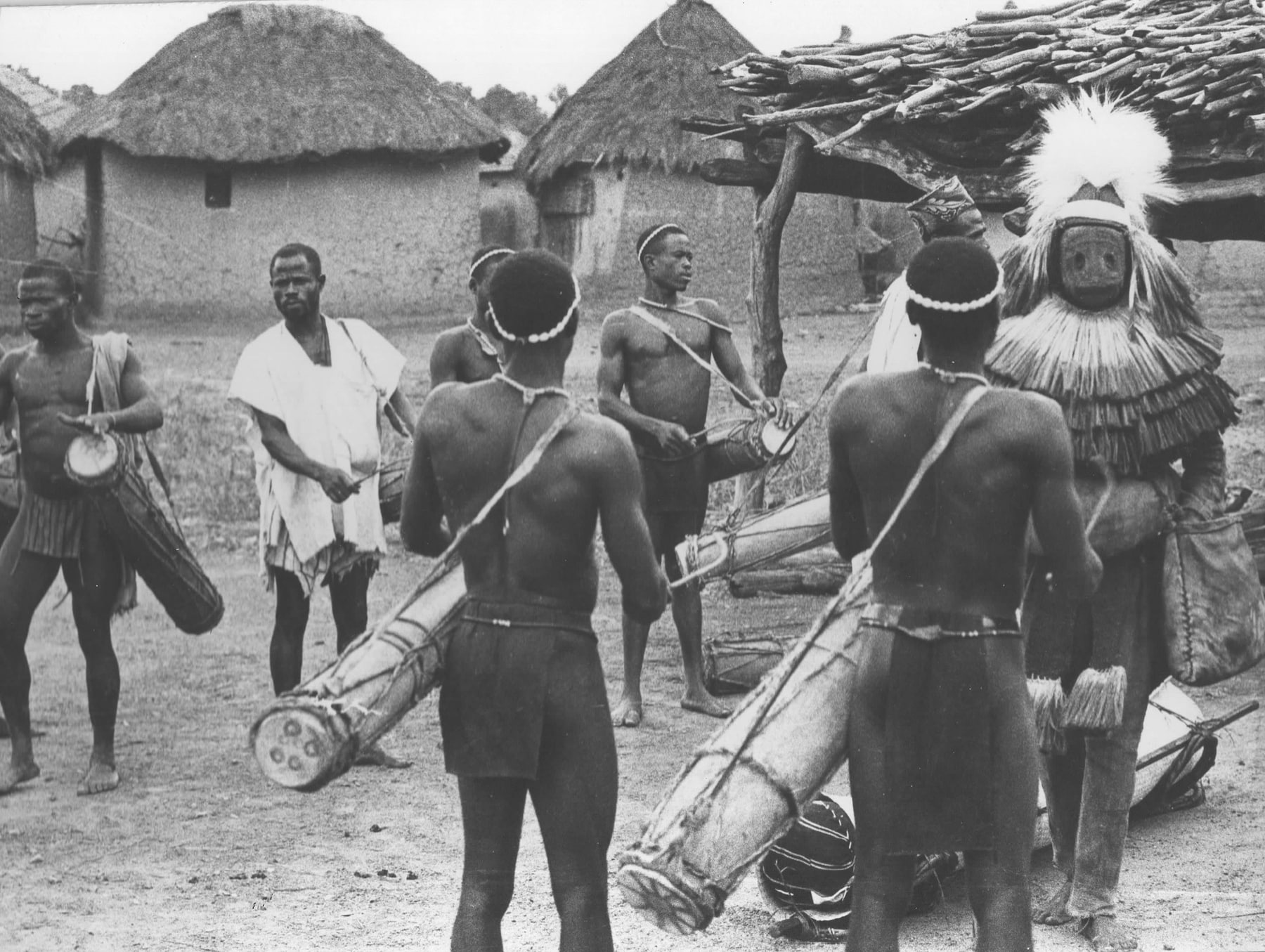

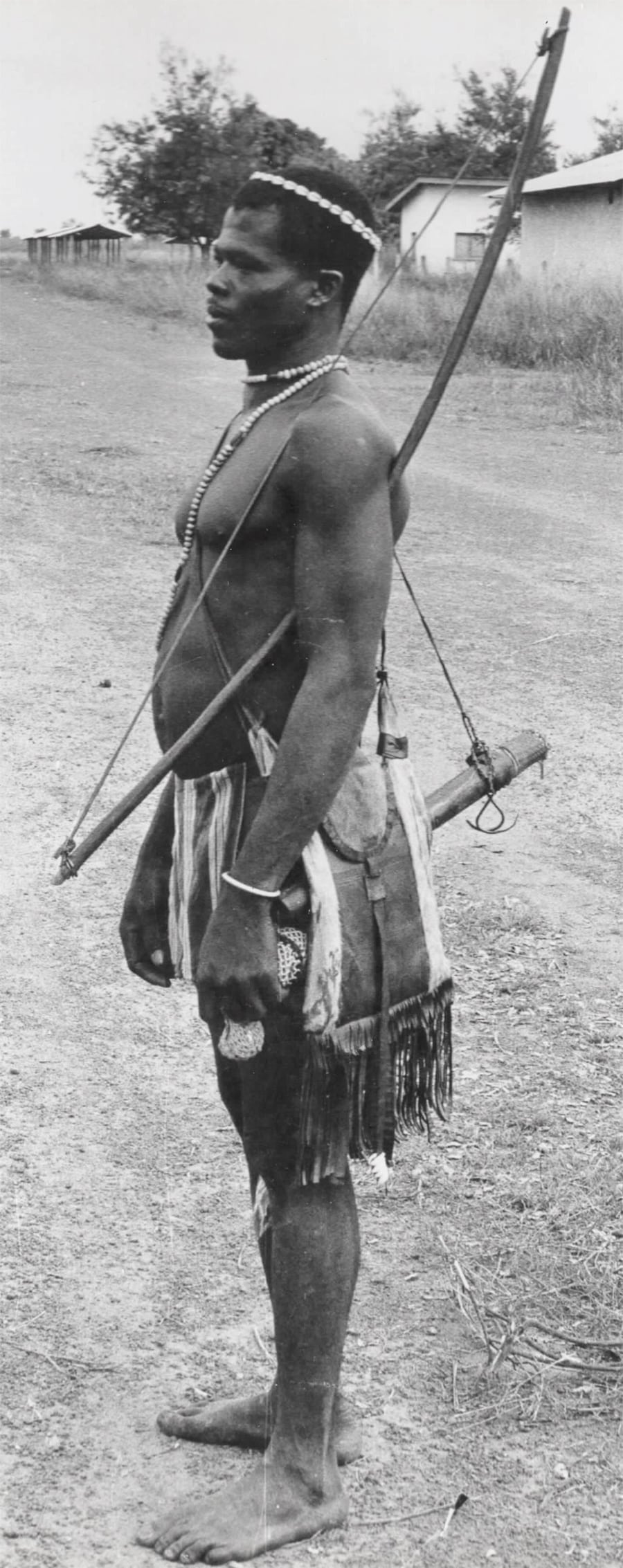

Then, at the beginning of my second year, a new seven-year cycle began. My generation, having lived three seven-year cycles, entered the Poro, the initiation society for men. In the Poro for seven years, young men of my generation learned all the life skills, responsibilities, and spiritual knowledge that would make them adult men − practical arts, leadership, sacred secrets, community service, and ceremonies. They conducted the funerals and village celebrations, danced the masks, and performed the rituals. One might call it “military service,” but it was much broader.

I told them that my Peace Corps service was like my “Poro,” an initiation for me into adulthood through service. This was a critical realization for everyone, determining my place in the village. Since we were starting a new project, building an improved market place, the elders decided that the Poro initiates would be the workforce, as part of their initiation.

As I was of Poro age working with my peers on this project, the chiefs and the elders knew where I belonged. They gave me the status of one of the Poro chiefs under their authority, whereas previously my social status within the village was a bit ambiguous. Thus, the connection between my Peace Corps service and joining the Poro society, clarified my position within the village social structure.

Experiences like these contributed tremendously to my understanding of traditional agrarian peoples and religions, the challenges of development, and the precarious survival of a way of life and cultures in post-colonial Africa. It introduced me to real world sustainable survival where agriculture and living harmoniously with the life cycles of nature coexist. This understanding has driven my work in sustainability.