I had hardly heard of the place in 1978, when a Peace Corps recruiter called and said, “How about Yemen?” My husband and I had been waiting for an assignment for a year. I gave an enthusiastic “Yes!”— and then asked, “Where is it?” (I should say, the country was then called the Yemen Arab Republic, or North Yemen, and separate from the Marxist nation of South Yemen until 1990.)

The poorest country in the Middle East, Yemen has a proud tribal culture, extremely rugged terrain, and, at that time, it had three paved roads. Taiz, the city that would be our home for two years, sprawls at the foot of one of the highest mountains on the Arabian peninsula: Jebel Sabir (elevation 10,000 feet.) We reached it via a harrowing four-hour taxi ride from the capital, Sana’a, along one of those roads, which twisted through mountainsides terraced with crops of millet, corn, coffee, and qat. As the taxi careened around heart-stopping curves, with no guardrails between us and the cliff, I tried not to look down at the crushed wrecks of cars below.

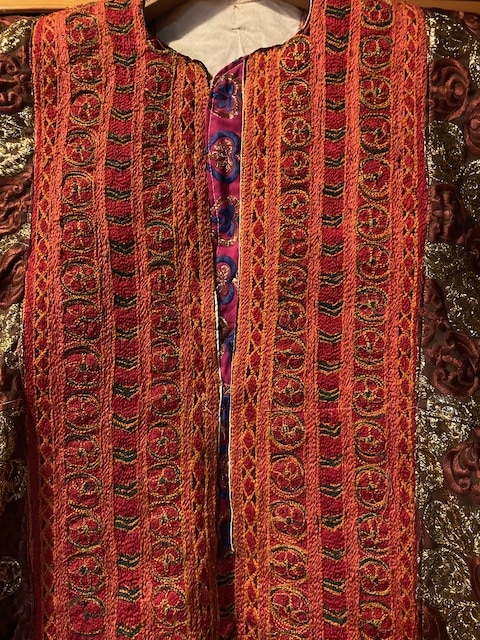

In the dusty, grimy, and noisy city, my eyes welcomed any signs of color. It was the Sabiri women that caught my attention. They stood out among the urban Yemeni women, who wore the long black veil and cloak, or sharshef, that covered them from head to ankle—a sign of Saudi Arabia’s increasing influence. In stunning contrast, Sabiri women wore bright dresses with lots of embroidery and outrageously long, wide sleeves that they tied back with string while they worked. Underneath they wore similarly colorful embroidered pantaloons. And, unlike their urban sisters, they did not veil.

These hard-working, rural women were a common sight in town. The people of Jebel Sabir lived in stone houses perched above ancient terraces clinging to the mountainside above Taiz. The women, both young and old, would come down the mountain, walking for miles on rocky paths, carrying on their heads baskets piled high with vegetables or bread baked in communal ovens to sell at the market. And at the end of the day, they’d hike back up the mountain.

Something else distinguished the Sabir women: their financial independence. People made a point of telling us, They have their own money. In traditional Yemeni society, women live their entire lives under the control of their father and, later, their husband. For some reason, tradition on this mountain empowered its women to retain their own wealth, which they displayed proudly in the form of substantial gold necklaces.

I loved seeing their intricate embroidery, their flashes of gold—and their open faces and confident gazes, even while I bargained with them at the market over a bunch of onions or an aromatic fresh flatbread.

A Taiz woman in the marketplace

Soon after we arrived in Taiz, I decided that I would like to have a Sabiri dress of my own. I asked around for a tailor who made them. My husband later found the tailor and surprised me with this dress, custom made for me. I wore it for a few special occasions—but all that stiff embroidery and scratchy fabric is quite uncomfortable. Discovering what it actually felt like to be inside that beautiful dress was a revelation that only deepened my admiration and respect for those independent women of Sabir.

Since I returned to the U.S., I’ve given my dress a place of prominence on a wall of every house I have lived in. It inspires me to talk about Yemen as I knew it, before the recent horrors, when girls were just beginning to be educated. I like to tell people about my work with girls as the librarian at a private coed school, and how I did everything I could to promote literacy, reading, and confidence. I like to hope that some of them grew up to become leaders in Yemen—and maybe had something to do with making Taiz a center of progressive spirit and female empowerment during the brief Arab Spring. And I wish them strength and courage to believe that they will make it up the mountain.