audio: Tigrinya Song: “Ghize” (Time)

audio: Sample from “An Anthology of African Music”)

I was a member of the first Peace Corps group to Ethiopia and the first American woman of Chinese descent to serve as a volunteer. While serving in Mendefera and later in Asmara I heard music from Eritrea for the first time. It was unlike anything I ever heard and so captivated my attention and imagination so much that I set about recording it. The name Mendefera derives from the high hill in the center of the town and means “no one dared.” For the town’s inhabitants it is a reminder of the resistance by the local people against colonization. I taught Science at St. George Middle School, and after school, English to working adults. Although I became an ethnomusicologist and have studied other music, none had a greater impact than that first experience of hearing Ethiopian and Eritrean music in Africa.

After teaching in Mendefera, I was transferred to a town called Decamere to teach high school English. On market day where sellers and buyers came from all over the region, I decided to buy some kitchenware. After buying a few items and walking about, I began to be pelted with pebbles and stones. In startled confusion I realized I was being stoned. Apparently, some local people in Decamere had never seen an Asian woman. Since the Peace Corps did not want this episode to escalate into an international incident, I was transferred to the more cosmopolitan city of Asmara. Years later I learned that people said my features, especially my eyes, looked strange and therefore I must be some kind of a witch.

While I was teaching at the Haile Selassie I High School in Asmara, I spotted Chinese Premier Chou Enlai walking alone near an intersection while I was across the street with my bicycle. An American official nearby told me NOT to wave, gesture, or acknowledge him because of American opposition towards communist China. Or was it because I was a Chinese American who could provide a field day for foreign journalists? How would the State Department explain US-China relations if I actually shook hands with the Premier? To everyone’s relief, I didn’t. Another international incident was averted.

During our two-month summer leave, a number of volunteers decided to visit South Africa. A good friend of mine was delegated to inform me that I could not travel with them because of South Africa’s apartheid policy. Of all the moments when I was reminded of my unique status, this blatant racism was the hardest to bear. I simply could not believe such discrimination actually existed, nor could I understand why my Peace Corps colleagues would want to visit South Africa when they knew other Americans could not. I spent my leave in Egypt where the sun shines all day. I didn’t realize my skin color changed from light yellow to a dark copper brown until I returned to my classroom in Asmara. My students beamed with amazement and shouted something that startled me: “You’re brown like us!”

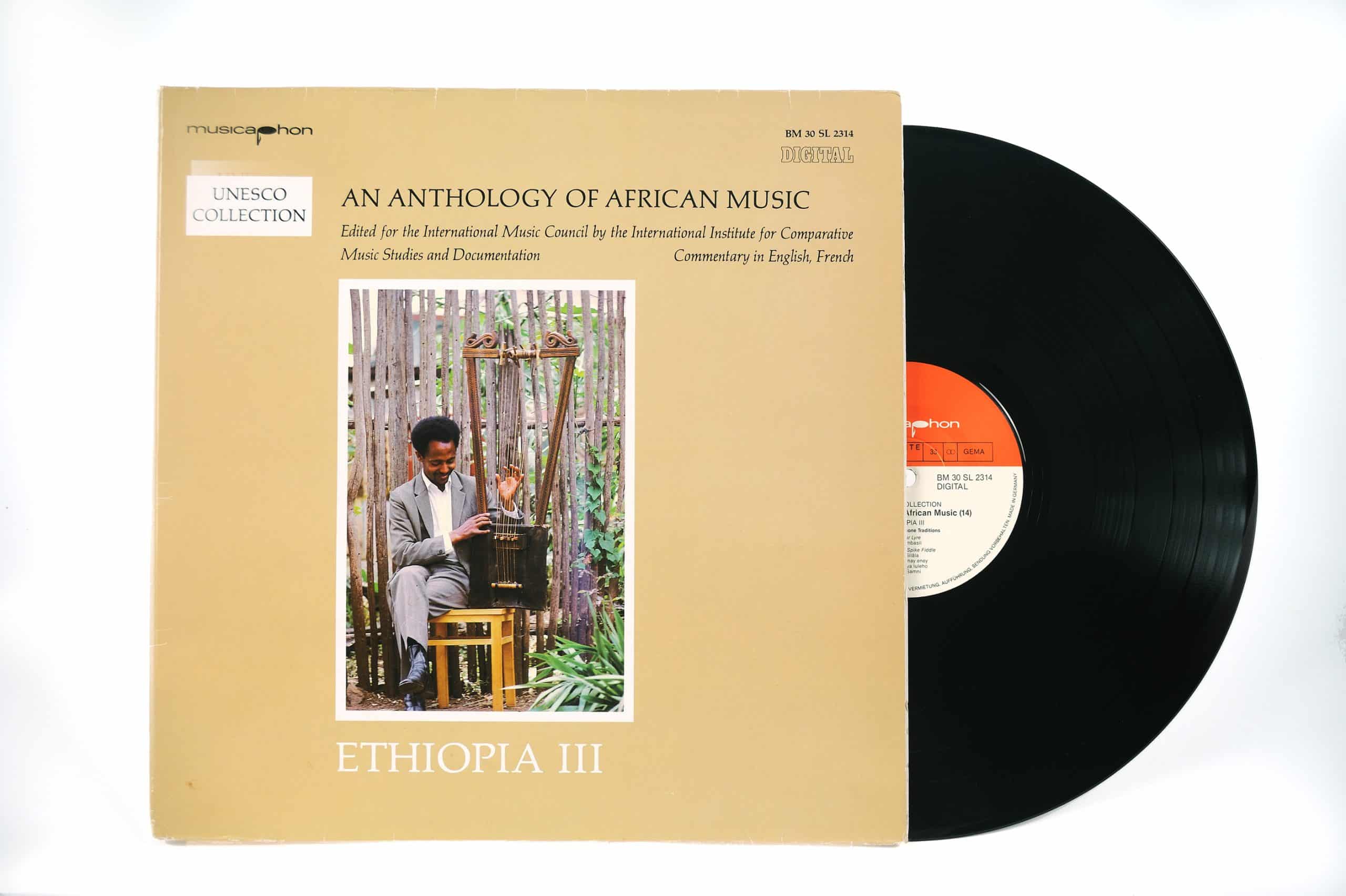

In 2000 I took the Tigrinya-language songs I recorded as a PCV in 1962-64 to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and played them to some young people I met. They did not know these songs but some of their parents and grandparents did. The songs were not familiar to them due to the 1974-91 political turmoil following Haile Sellassie’s removal in a military coup. The military regime that replaced the Emperor banned love ballads, religious songs, and musical instruments associated with religion. The ban prompted me to publish some of my 1972 field recordings of pre-revolutionary music, resulting in the 1986 UNESCO recording ”. “Three Chordophone Traditions After 1991, the ban was lifted. This music is a historical document of an oral tradition. One could say I am returning these songs to the people who first gave them to me, whom I still feel privileged to know. I hope that the next generation will enjoy these songs, and pass them on. I’ve donated recordings and a baganna (lyre) to the Peace Corps Museum.