When President Kennedy asked, “What can you do for your country?” I wrote a letter volunteering for the Peace Corps. Early in 1962, with a newly granted liberal arts degree and no plans, my invitation to train for an urban community action project in Colombia arrived in a big fat manila envelope.

Did I know anything about urban community action? Did anyone know what urban community action meant? In those early years, Peace Corps was an experiment; all projects were in different stages of research and development.

During the sixties, Colombia’s urban population was rapidly growing as campesinos migrated to the cities for improved living standards and work opportunities. They built tin and cement block shanties on the mountainsides and tried to eek out a living. The Peace Corps’ intent was to place PCVs in these barrios to help the people organize and seek resources from city governments.

That was not the case with my assignment. Our three-person team’s placement had two motivations: (1) To satisfy the Medellin mayor, who requested that PCVs be placed in the city’s center of vice, Barrio Antioquia, to show his intentions to improve this area; and (2) To foster good relations with the American community residing in Medellin.

The American Consulate’s staff and businessmen responsible for developing commerce between Colombia and the USA made up the American community in Medellin. By coincidence, Joanne Haahr, the wife of the Consul-General James Haahr, was from my own small town in western Pennsylvania. Our mothers often played bridge together.

Our team soon realized that community action programs were not viable in our neighborhood. We could not move; it was silently mandated we would continue to live and work here. One key hindrance to our effectiveness was the fact that Barrio Antioquia was the headquarters of ousted Colombian dictator Rojas Pinilla. His lieutenants railed against us weekly in community meetings. “Yanquis, get out of Colombia! Peace Corps is not wanted here! You do not belong here!” Thus, we were handicapped in developing community action programs.

Instead, we found our niche working with local university students. With assistance from the PCVs who were working as physical education professors, we initiated a youth sports club. Working with these young people and women from the Centro de Salud (health clinic), we raised funds and installed a children’s playground. As we were departing, the women were in the process of setting up an infant nursery and day care center in the health clinic.

Through the grapevine, I learned that Ron Atwater, Colombia 1 PCV, had organized a ruana cooperative in his post at Lenguazaque in the Departmento de Cundinamarca in the Andes Mountains.

These ruanas (woolen shawls) were made of 100 percent virgin wool, perfect for the Andean climate. The process began with raising and shearing sheep for their wool, then spinning their wool into yarn. Next, workers dyed the yarn with natural dyes. Finally, artisans wove the yarn into a ruana using a special loom. A totally manual process!

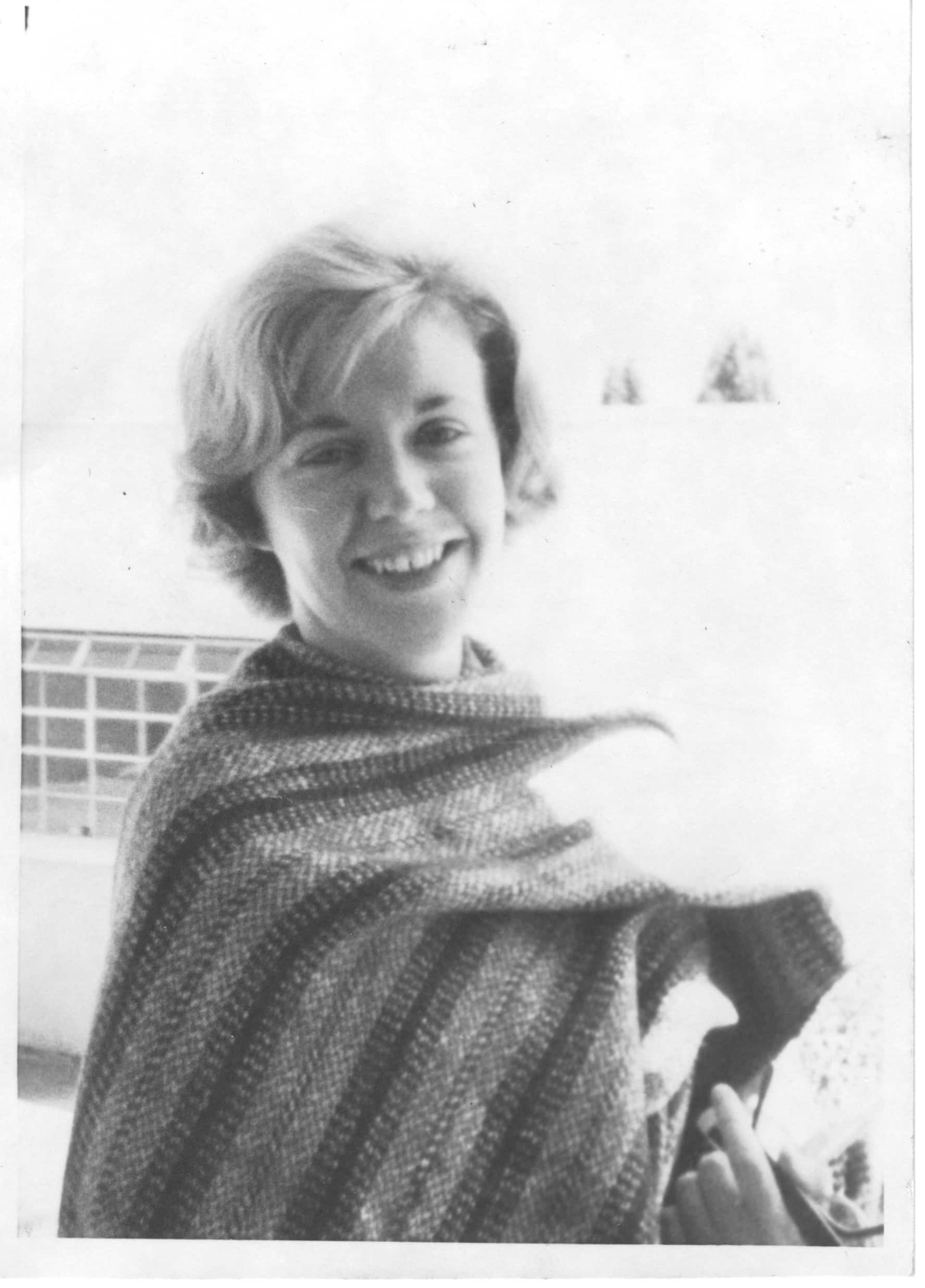

Ruanas from this coop were sold at the Hotel Tequendama, Bogota’s premier four-star hotel. I was thrilled when my order for a ruana was fulfilled. It became the ultimate keepsake from my time as a PCV.

During the 1960s, ruanas were exported and sold at Saks Fifth Avenue in New York City for premium prices. Today, ruanas are worn all over the western world, in multiple fabrics and colors. The word ruana is now part of the fashion lexicon.

The open markets of Medellin also had beautiful ruanas—brightly- colored cotton woven ones. My ruana was perfect for my Antioqueno lifestyle —a shawl for cool days or chilly nights, a blanket for my bed, a pillow, a picnic blanket, or a seat cover when riding in a chiva (rural bus). Easily stored by tossing over the single Adirondack chair in my apartment, my ruana became a room decoration. The one-size-fits-all feature is not to be underestimated!

The Colombian people have survived many years of civil war and violence. The ruana reminds me of the persistence, courage and tenacity of the Colombian people in their struggle for progress and development.