Beyond the exotic game parks of Uganda lay 75 square miles of the papyrus swamps of Busaba, Bukedi District. Here, there are no villages: instead, folks live in a family compound or ehidda—a Lunyole word meaning “stomach”—a collection of subsistence farms led by elder males. My wife Denise and I had been dropped off with some furniture to offer health education and to cure trachoma, an eye disease. But the scattered nature of the ehidda as well as the many other burdens faced by its residents forced us to look beyond trachoma.

So, here we sat on tiny, wooden stools chatting with Abulamu Walyoba and his silent wife. We’d come to ask the headman, “Why are there so few pit latrines?” We learned that termites eat the wattle holding up the flooring. Collapse. Fear. Injury. Hmm. My assistant, John Wamudanya, and I returned with a plan. How about a reinforced 900-pound concrete slab, specially treated poles, a tin roof, a gutter to collect rainwater for drinking, and a mahogany hole cover? Based on the trust this much-respected family had in us, his ehidda agreed to dig a 15-foot, 2’ X 4’ pit in 20 compounds and convince two other headmen and their groups

I enlisted my Asian-Ugandan friend, Gondemar S. Patel, who got the Lions Club to pay for the tin roofs, nails, clips, and gutters; the Government Forester who agreed to provide treated eucalyptus trees at cost and the hole-covers at no cost; and the Ministry of Public Works which agreed to build the slabs at a reasonable price with free delivery. The next stop was USAID which, after looking over the plan, agreed to fund us with $1,200.

We always began digging the holes in the early morning and covered the hole with tin so no one would fall in the hole during the night. One morning I visited one of the holes, and said..…

“Wait, what was all that raucous noise? Something’s wrong!” I just knew it. I glanced into the hole.

“Dear God in heaven!” I exclaimed and turned to John and Abulamu with raised eyebrows and a sinking feeling.

“A giant rat,” John said, between giggles.

With a broad smile, one of the men climbed down our makeshift ladder. Was he simply putting on a brave face, I thought, despite his fear? Where was his machete? All I could see were his bare hands. A couple of minutes later, John’s helper plopped a hapless omnivore on the ground at the edge of the hole.

John almost fell down laughing at my surprise. What to me was a threat was only lunch for the latrine crew. Saving Mr. Rat for a later meal, we contented ourselves with finger millet, which tastes to me like ground coffee beans, or cassava root. If you are not familiar with cassava; it is that dear but bland plant that can grow 40 feet deep into the earth and preserve water during a drought.

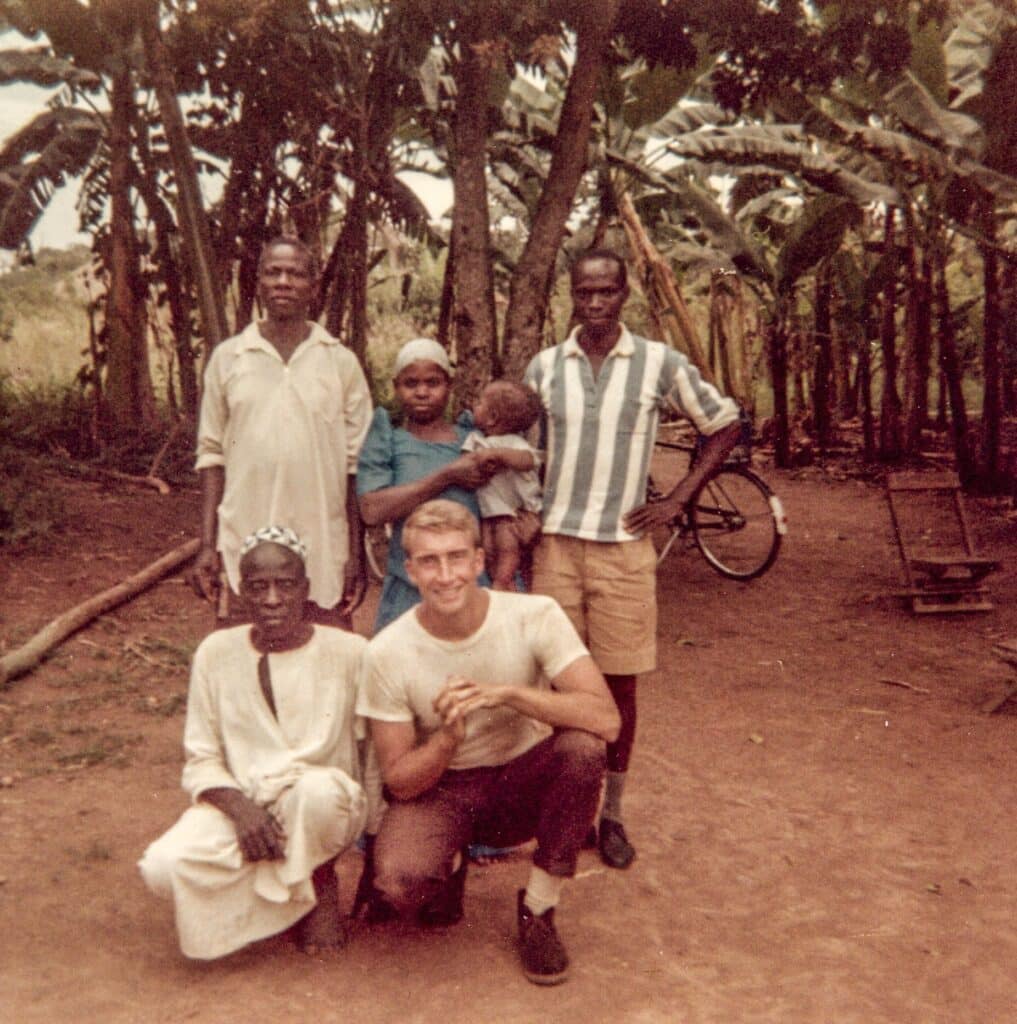

After months of grinding work, we built a total of 65 latrines. As part of the funding, USAID required that we show the American experts our results. So, Abulamu hosted our USAID overseers, a couple of easy-going ex-farmers, to view our latrines and share a meal — a pile of steamed plantain on banana leaves, a bowl of wild mustard with tomatoes, and banana beer sipped through a communal straw.

As John Wamudanya translated from Lunyole into English, one of the Americans pulled out a pack of Marlboros. Noticing the silence, I whispered, “Pass around the pack.” Each of the Ugandans—none of whom could afford to smoke—took one and slipped it behind an ear for later sale. The other American passed around a second pack. Those “capital-city” Americans told me later that they hadn’t had such a good time in a long while. Denise and I had a memory to last even longer.