In much of the world, people take their furniture for granted. Among the people who live on Pacific islands, it is taken for granted that furniture is unnecessary.

My very first challenge in 1967 as a Peace Corps trainee began on Udot Island in the Chuuk Lagoon (Micronesia). Our little western-style cabin had a floor covered with a rough, utilitarian pandanas mat. I was unprepared for sleeping on the floor. I soon learned that the local Udotese slept on well-crafted mats fashioned by plaiting leaves of the pandanas, a tree that grows abundantly along the shores of most Pacific islands.

I found a shop that sold local crafts and came upon just the right mat for sleeping like a native. After three months of Peace Corps training, I boarded a field ship in Majuro (the Marshall Islands’ district center) to take me (and my sleeping mat) 400 miles northwest to Rongelap Atoll. Its main and only inhabited island had a population of about 120 residents, all living on three-square-miles of land.

My assignment was to start a coconut rehabilitation project. Coconut was the main source of income for outer island people. I helped several local producers form a cooperative to undertake a variety of tasks to improve coconut production. These included clearing palms smothered with vines, felling old and unproductive palm trees, and planting seedlings to replace them.

To promote more varied nutrition among Rongelapese, some residents and myself prepared two vegetable gardens and planted them with a variety of seeds imported from the U.S.

During the time I served in the Peace Corps, Micronesia was a U.S. trusteeship. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture the many dead and diseased trees on Rongelap Atoll’s northern islands were the result of damage caused by the coconut beetle. I had difficulty believing this, however. Fourteen years earlier, in 1954, a hydrogen bomb had been tested on Bikini Atoll, only 80 miles west of Rongelap. The wind carried fallout eastward, with the highest concentrations settling on Rongelap Atoll, and lesser amounts further east. Rongelap was evacuated soon after the blast by the Navy, but former residents were allowed to return three years later, in 1957. Fallout was much greater on the islets along the northern lagoon, but none of these were inhabited.

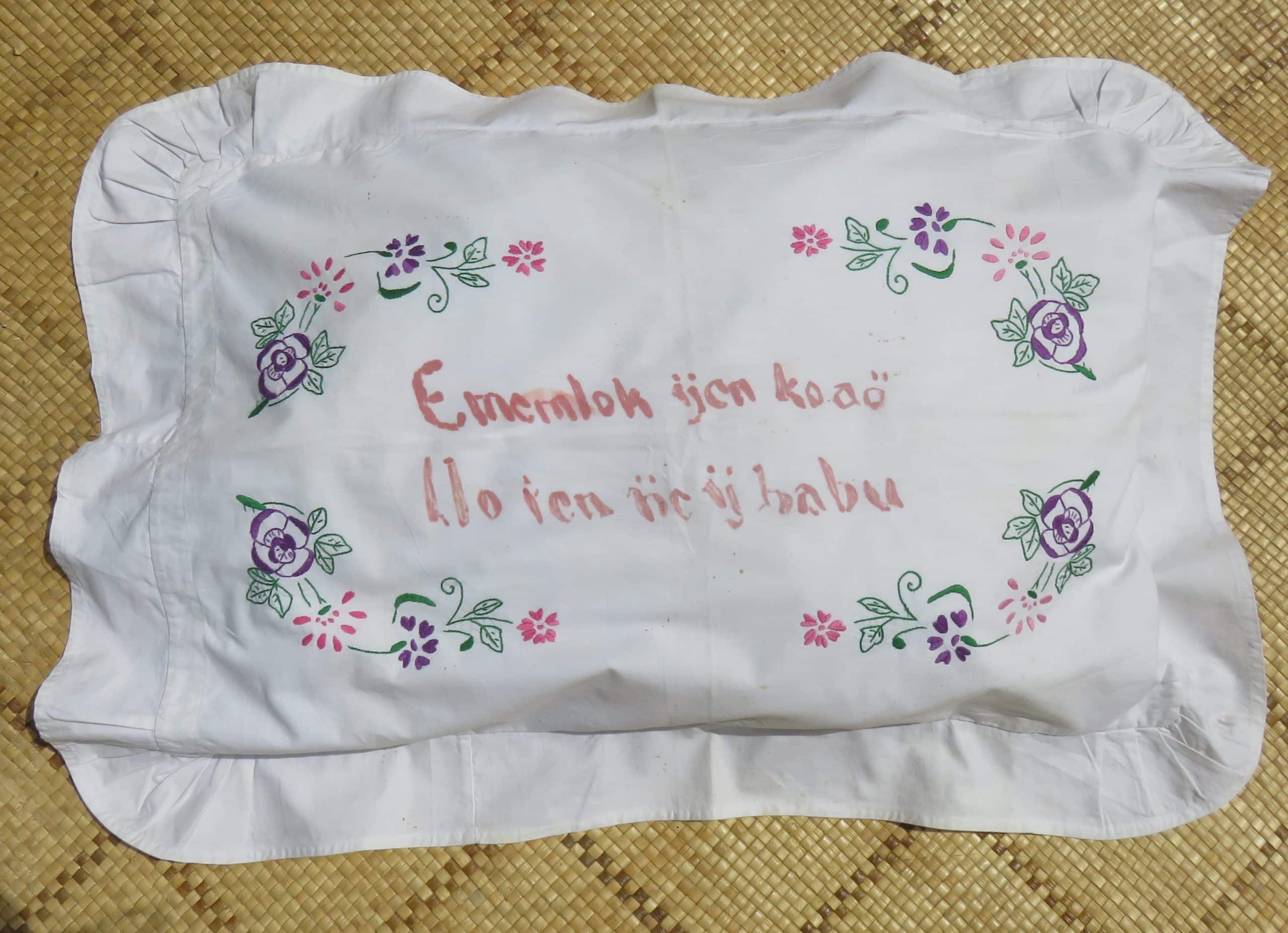

As I adjusted to work and sleeping accommodations on Rongelap, a woman from my neighborhood came to my door with a gift. She had sewn a pillowcase and decorated it with embroidered flowers and leaves. She inscribed the pillowcase with an indelible marker (the writing now faded after many washings) that said: Ememlok ijen ko aö, ilo ien ne ij babu, which means (roughly translated) “My place is better with this pillow when I go down to sleep.” Indeed, it was!

A pillowcase made for me by my neighbor

Several months after my arrival, a ship brought some former residents back to Rongelap, among them an older couple named Abia and Kalal. They owned the house next door to the one the Peace Corps had arranged for me to live in. Kalal owned a kerosene refrigerator, among other comforts not common on Rongelap. As an act of friendship, he offered me a foam rubber mattress (probably from an outdoor lounge chair) which he had brought with him. He said that with this mattress I could then sleep like a ribelle, meaning as a foreigner. I was much obliged and wasted no time in placing the mattress under my mat.

In 1985, sixteen years after I left my Peace Corps assignment, the people of Rongelap arranged with Greenpeace to be removed again from their contaminated homeland. They realized that three decades after the series of nuclear detonations, the land was still too irradiated for human habitation. As recently as 2019 scientists found that some of the northern islets were as “hot” as Chernobyl, so many years after its reactor meltdown of 1986.

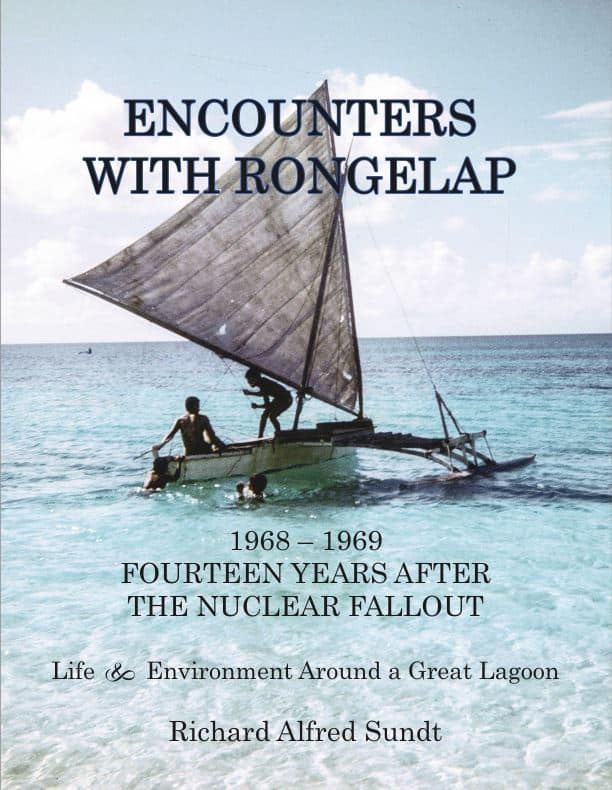

In October 2019, I published Encounters with Rongelap, a book describing my experiences as a PCV. In it, I included an essay (which I translated from Marshallese) written by John Anjain, who was Rongelap’s magistrate at the time of the nuclear explosion. He described the day of the fallout, the days immediately after, and three years of exile before being allowed to return home. John also wrote about the radiation illnesses the people suffered during these and subsequent years.

Human-generated disasters have made life difficult for people living in the low-lying atolls of the Marshall Islands. Although atolls lack the abundance of the Pacific’s higher islands, the Marshallese long ago learned to harness the resources of the ocean and land to fashion for themselves a sustainable and self-sufficient life—a life that today, the whole world aspires to achieve.