I was lucky to be one of three volunteers asked to start the first school for children with special needs in Westlands, near Nairobi. Treeside Special School was funded by Mr. Menya, a Kenyan businessman whose disabled daughter was turned away from the government schools. However, Harambee (“Let’s all pull together” in Swahili) served as a model for creating more schools throughout Kenya. A small Anglican Church opened its doors to be used during the week as Treeside School, and a small admin bldg. was added. Harambee also provided the impetus for many children with disabilities in Kenya, previously hidden at home, to attend school. The teachers at Treeside offered a shame-free education for parents of these children.

Mr. Menya provided school uniforms to all the new students at Treeside School. The children were from age 6 to 16 years old. I was impressed that they had similar-sounding names and smiling faces. Teachers spoke to the students in Swahili; however, the students spoke Swahili, English, and other local dialects. We had children from Uganda, and many Kenyan children who were not accepted into government schools and had nowhere else to receive an education.

Soon after Treeside Special School opened, Betsy, Barbara, and I sorted students into groups by age and disability. We developed the curriculum, and planned daily programs. We identified individual disabilities—such as speech impediments—and prescribed special needs. I quickly realized that the older children needed life-skills—such as routine cooking skills and finding their way around the community. I brought students to my home twice weekly, taught them how to measure ingredients while cooking, how to read community signs, count bus fares, or read books. They enjoyed many of the Kenyan animal stories including Rudyard Kipling’s “How the Zebra Got its Stripes,” and “How the Giraffe Got a Long Neck.” Our experiential approach to reading was based on Swahili writing, which—unlike English—uses easily-pronounced phonetic words when written.

The children varied widely in their ability, parental involvement, and financial need. Jack had developmental delays; he verbalized loudly and repeatedly, and flailed his arms while speaking. Almost 6 feet tall, Jack seemed intimidating, but we learned how to change his behaviors. After we taught him more appropriate reactions, he was loved by many who understood his friendly nature. His single mom worked at the Kenyan National Library and was a wonderful example of acceptance, appreciation, and patience to other parents.

In Nairobi, I became known as “that teacher with the wild kids.” I knew my students had poor manners—jumping on the bus, pushing past those trying to get off. Watching my kids on the bus, I also knew that they brought some strange reactions from other passengers. However, thanks to the Harambee philosophy of pulling together, many passengers learned to appreciate special-needs children and lost their fear of them. I took the children to visit restaurants to learn how to eat meals appropriately without raising their voices. Soon, shopkeepers and waiters got used to us. Over time, we changed the image of my students from “wild kids’ to “likeable and fun kids.” That gave me a sense of accomplishment.

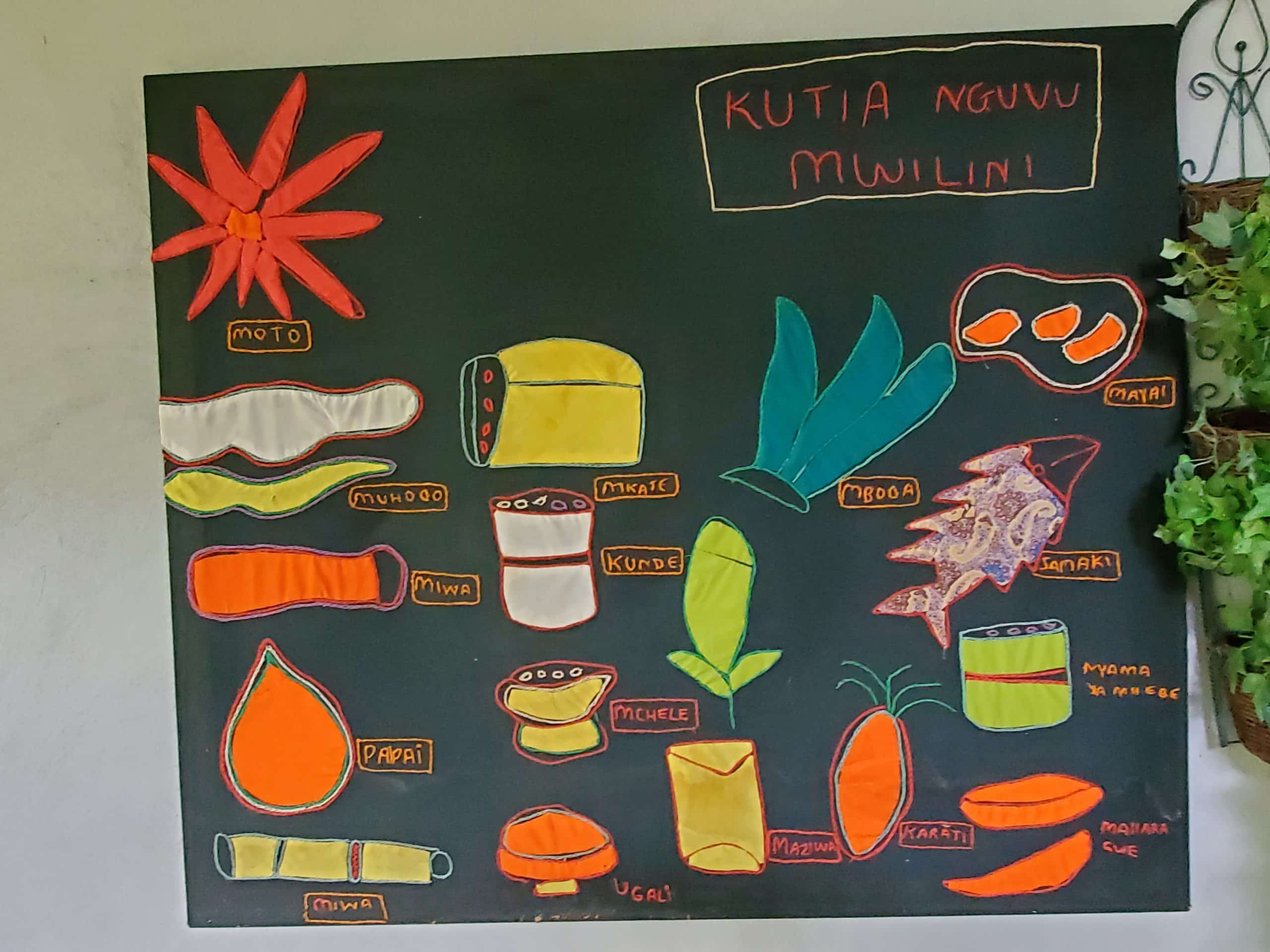

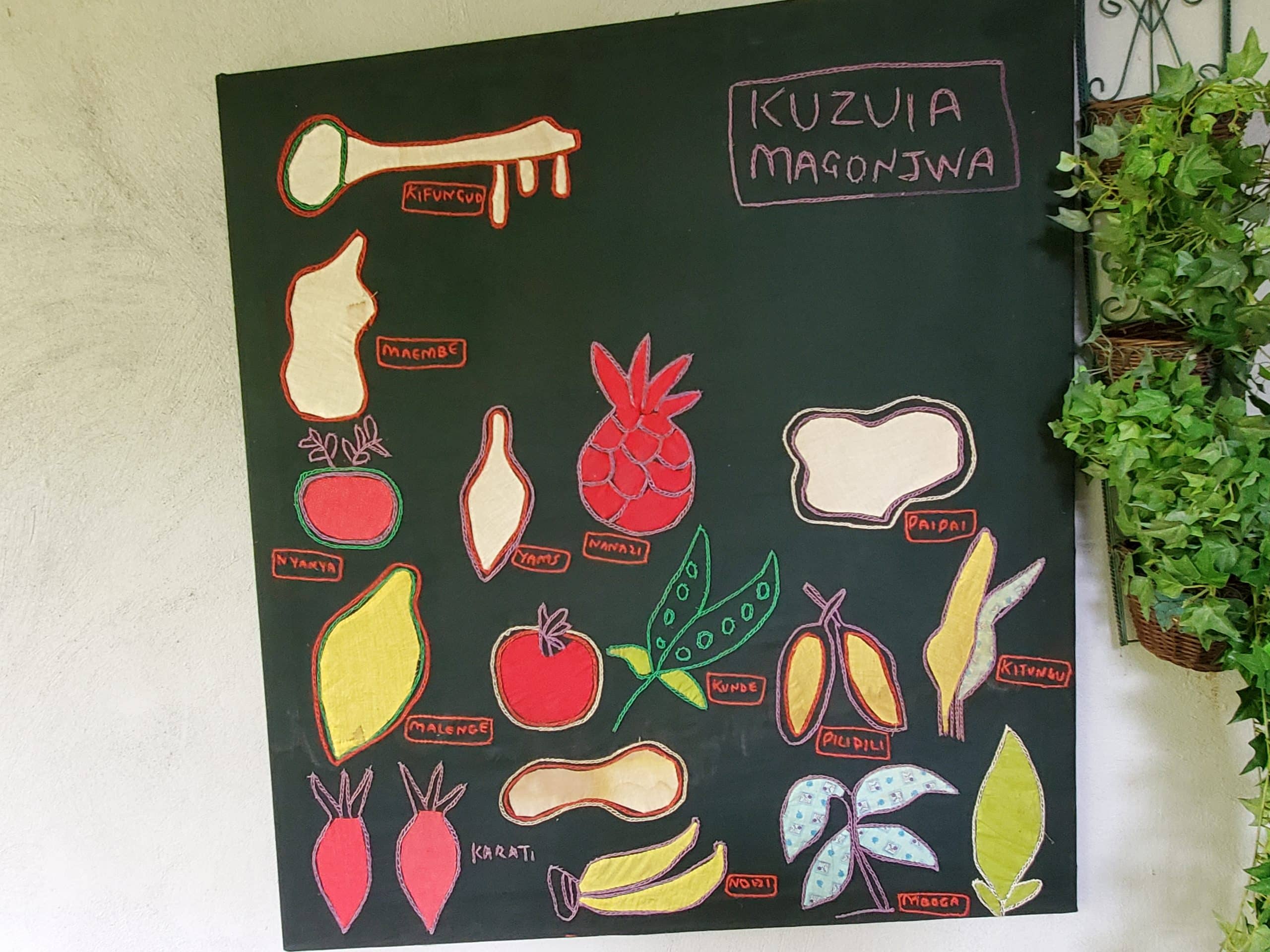

Understanding that good nutrition was an important part of our work with parents, I asked a local woman to create embroidered food group charts to teach nutrition and local customs. Although I didn’t seek them out for myself, I taught children that insects are an important part of the protein food group. One of the parents invited me over for a special meal of stew, and I graciously accepted—not realizing until later that the content of this delicious stew was grasshoppers, and quite delicious! We used the embroidered murals to teach both nutrition and reading. Students sounded out the names of important foods.

Treeside School became a model school in Kenya. We trained a local teacher assistant to developed methods for teachers whose classroom experiences were limited. When we left Kenya, two Danish teachers came to work with Kenyan special education teachers.

I will always appreciate the opportunity to be part of the significant contribution we made to Special Education in Kenya. This country taught me to value the ”Harambee” Spirit and it has shaped my life ever since.

The list below gives the Swahili/English meaning of the Food Charts donated to the Museum.

Kutia Nguvu Mwili = Strengthening the Body

Moto = hot foods, chili peppers

Miwa = sugar cane

Papai = papaya

Mkate = bread

Kunde = legumes

Mchele = rice

Ugali = maize flour porridge, a staple

Mayai = eggs

Smaki = fish

Nyama ya muege = beef

Maziwa = milk

Karati = carrot

Kuzuia Magonjwa = Preventing Disease

Kigungo = Key foods

Maembe = mango

Nyanya = tomato

Yams = yams

Nandazi = pineapple

Karati = carrot

Kunde = legumes/beans

Pilipili = hot peppers

Kitungu = onion

Mboga = vegetables

Embe = mango