“Là-bas” literally, it means “over there.” But where is that? In Gabon, là-bas is anywhere except where you are. Where is the river? Là-bas. Where is the plantation? Là-bas. Where is the moon? Là-bas.

Anytime I asked for directions, the answer was inevitably là-bas. “Mais ça c’est où?” But where is that? I asked, exasperated.

If my sought-after destination was up the hill, the answer would be, “En haut là-bas.” Up over there. If it was down the hill, their reply was, “En bas là-bas.” Down over there. And to my endless amusement, instead of pointing with a wave of a finger or a hand, the villagers would usually point with their lips, a long, puckered extension in the direction I should travel.

Every time I tried to get to là-bas, I found myself confronting an eternal African paradox: là-bas really meansyou can’t get there from here. Like a carrot dangling in front of your nose or like a gerbil chasing infinity on his wheel, là-bas always loomed just out of reach.

Enchanted with markets

One day in the village of Endama, I took the road to là-bas. My host father, Jean-Jacques, proposed a day trip to Minvoul, a town 120 kilometers to the north. He was the owner of one of the two trucks in Endama, which made him the source of much envy and resentment. However, any time he proposed a joyride, all villagers within earshot became his friend and clambered aboard.

Jean-Jacques described Minvoul to me with excitement: markets loaded with produce and supplies brought across the border from Cameroon, wonderful things unavailable even the short distance south to Oyem. With no centralized agriculture and few factories, Gabon is highly dependent on foreign imports. While villagers could potentially survive on their own plantation crops, their diet is amply supplemented by the cheap palm oil, rice, salt and tomato paste trucked or flown in from other countries. Even the vibrant fabrics proudly worn by women and men arrive largely from abroad.

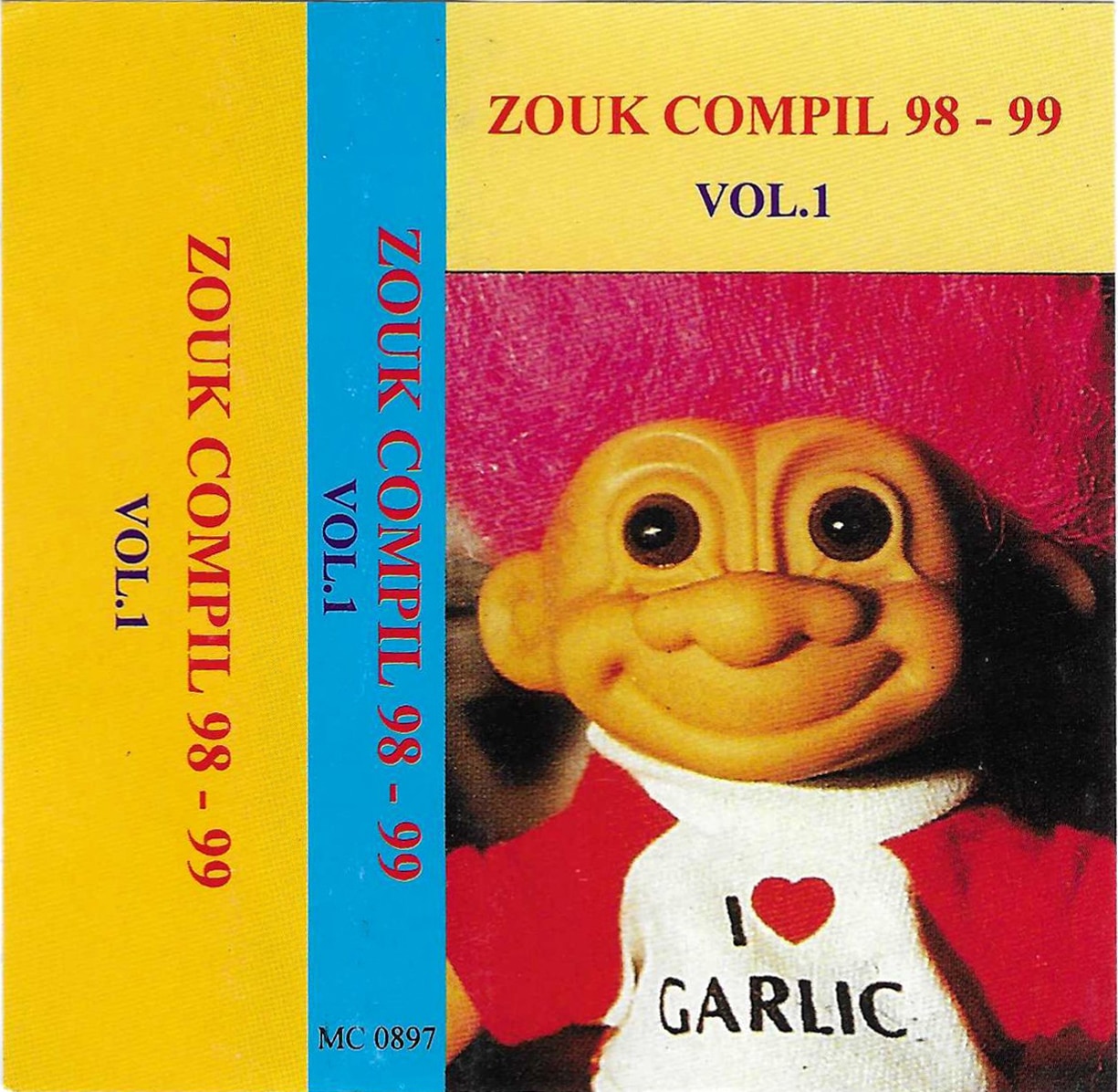

I was easily entranced by the colors, smells, and utter chaos of the stalls of Oyem markets. They were dirty, disorderly and wonderfully exotic. One could easily get lost in the alleys and nooks or wedged unwittingly between piles of dried bat and baskets brimming with hot peppers. You could just as easily get your pocket picked and see the thief melt into the maze of passages. I never carried more than a few thousand Central African Francs (CFA), equivalent to a couple dollars, on me at any time. As a result, one of my favorite activities consisted of searching for the most outrageous treasure for under 1000 CFA: a pair of Abbidas shoes or Neki shorts; a cassette tape bearing a troll doll in an “I Love Garlic!” t-shirt; or a piece of not-quite-dried-out cow skin. If these were the wonders of the Oyem markets, I could not even imagine the surprises awaiting me in Minvoul.

Road to Minvoul

Jean-Jacques declared his final, “On part, oh!” Let’s go! And villagers emerged from the woodwork of their humble houses to jump into the bed of his pick-up. He offered me the seat of honor, directly next to his driver, while he took the seat to my right at the window. It was no honor, however, to have the stick shift jammed into my thigh over rut-filled, unpaved roads. So, at the first opportunity, I shifted to the back of the truck, trading in local custom for fresh air.

Within 20 minutes the truck stopped at the side of the road. “This is my mother’s village,” said Jean-Jacques.

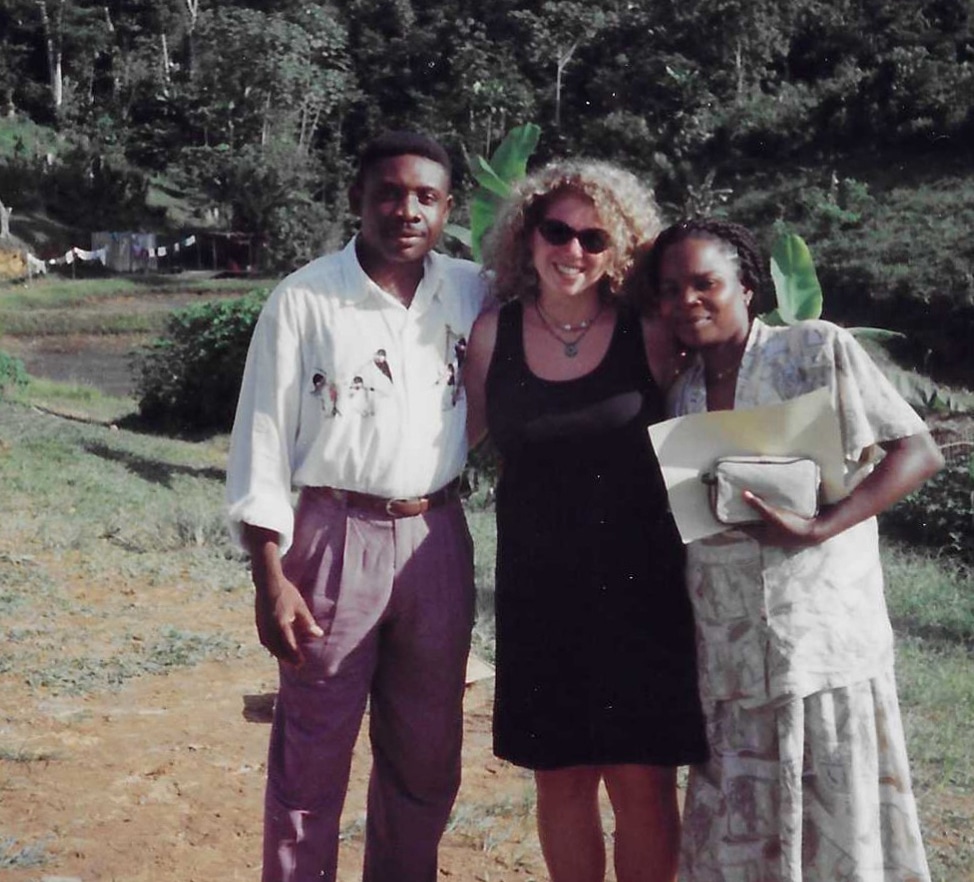

There beneath a giant acacia tree the family greeted us with jugs of palm wine. Did they know that we were coming or was this a typical Sunday morning activity? I suspected both. Jean-Jacques introduced me to his relatives as his new daughter, and they greeted me with familial hugs and handshakes. We drank, we laughed, we stayed for an hour or two before we loaded up and moved on.

Not far down the road, an old friend waved Jean-Jacques down. We got out, drank some more palm wine and malamba (sugar cane wine), joked, laughed and then loaded up again.

Four more stops down the road and we were nowhere near Minvoul. The market was long closed and the sun was starting to set. Minvoul—our là-bas, our Shangri-la. We just couldn’t get there from here.

Slightly disappointed, and with slightly spinning heads from all of the cups of malamba, we drove back to Endama in the dark. With the cool night breeze of the dry season providing an unusual chill, I acquiesced to sit in the front, middle seat and remembered the title of a book by a photojournalist who made his career in Africa and lost his life far too soon: “The Journals of Dan Eldon: The Journey is the Destination.”

This journey was my destination. I had learned that là-bas is not a place, it is how you pass your time along the way.

The author is a marine scientist and executive director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Global Marine Program. She received a 2019 MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant.