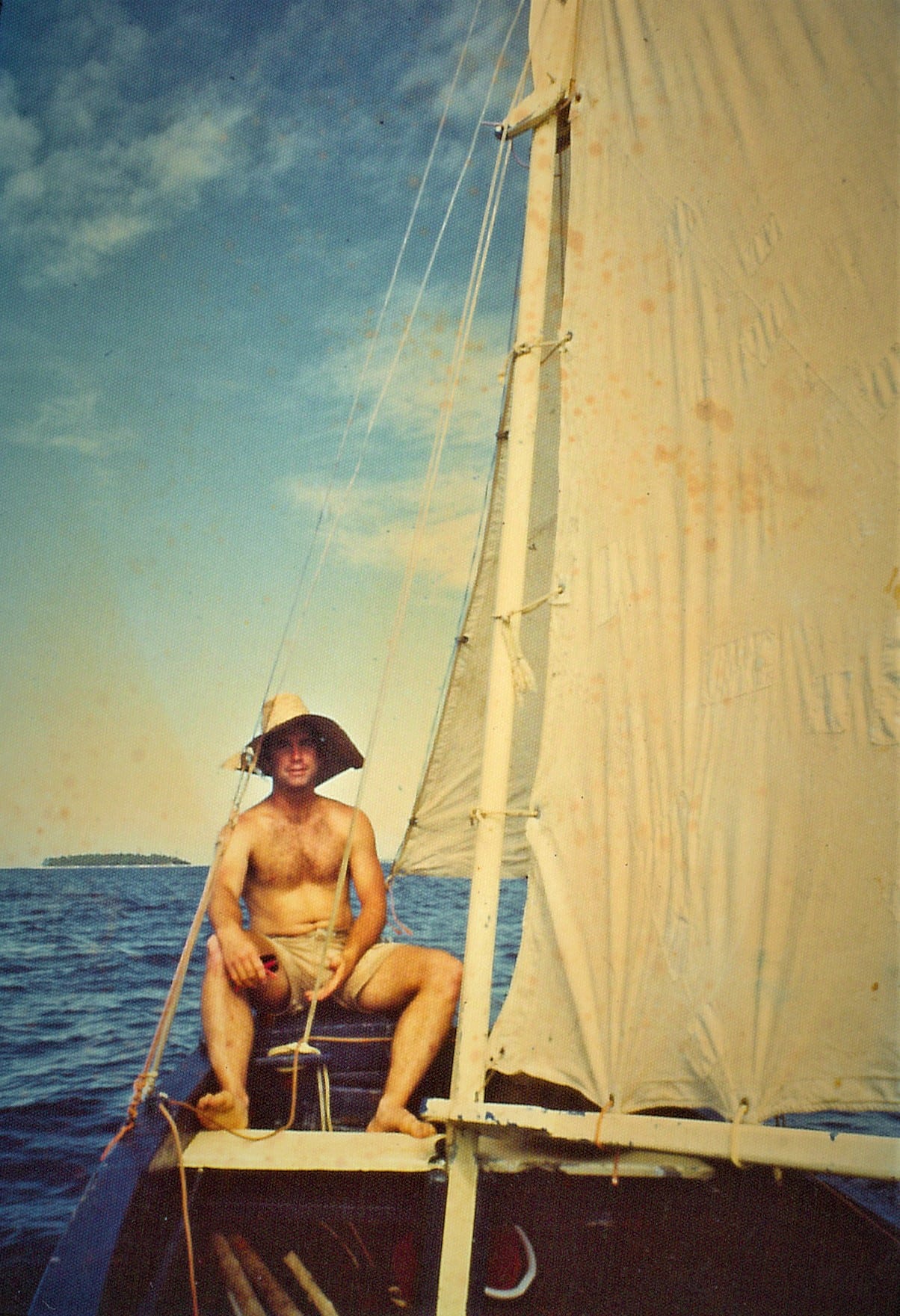

I was seven years old in 1961 when John F. Kennedy announced his idea of a Peace Corps, planting a seed in me to be part of his vision for Americans to go abroad and make the world a better place. That seed took root some 15 years later when, at the age of 23, I volunteered in Nuku’alofa, Tonga as a water supply engineer for the Tonga Water Board. I helped to solve water problems throughout the Kingdom’s 40-some inhabited islands scattered among Tonga’s 270,000 square miles of ocean in the South Pacific.

After I had worked on Tonga’s main island for six months, Tonga’s Minister of Health, Dr. Sione Tapa, directed me to travel to the outermost island group known as “The Niuas” to inspect their water supplies and recommend improvements. I found myself among 60 passengers huddled under a tent canopy on the lower deck of a cargo/ferry boat called the ‘Ata, motoring slowly out of the harbor with crated pigs and chickens – gifts from families visiting their loved ones.

We were on the ‘Ata’s semi-annual supply run making stops along the way to exchange cargo and passengers. When the weather was clear and calm, I would lie on the top deck to take in a panorama that turned magical at night – the sky was lit up by millions of stars and occasional meteors, while the ocean responded with millions of phosphorescent particles, lighting up like green neon in the boat’s wake. One night of being treated to this display seemed to make it worth the thousands of miles I’d traveled and the work I would put in as a Peace Corps Volunteer.

After a week of rocking and rolling on ocean swells, punctuated by stops at several islands, the ‘Ata arrived at Tonga’s most remote, inhabited island and dropped anchor about 50 meters offshore. Niuafo’ou has no safe anchorage for ships, much less a harbor. Its mail was delivered in biscuit tins tossed overboard from passing freighters to islanders who would canoe or swim out to the ship to retrieve it. This unique method of mail delivery gave Niuafo’ou its other name, Tin Can Island, as it is known to most everyone in the Pacific.

The people kept a large wooden raft at a little black-sand beach between volcanic rocks, tied to a stake with a long rope. They paddled the raft out to the ‘Ata, letting out rope as a landline tied to the shore. They roped the raft to the ‘Ata, loaded it with passengers, and then used the rope landline to pull the raft back to shore. This procedure was repeated until all people and cargo were transferred from boat to island, and it is practiced in much the same manner today.

My hosts served an evening meal of taro and fish and I joined a small group of men and a young woman in a faikava, a Tongan ceremony dedicated to the consumption of kava, the national beverage. Kava is made by pulverizing the roots of the kava plant into a fine powder and mixing the powder with water. It contains mildly psychoactive chemicals which act as a sedative. They welcomed me as a representative of Tonga’s Ministry of Health and Water Board to assist with their water supply needs. It was also my opportunity to explain my assignment to the island’s leaders and to gain their endorsement needed to complete my work the following day.

The men told me about their daily lives of farming and fishing, and how they obtained the water they and their animals needed to survive. They dug shallow wells into the volcanic rock, but the wells were often contaminated by storm runoff and animal use. Their most dependable water came from rainwater catchments from roofs and gutters at churches and schools but these were leaky and inadequate. I planned to visit village systems and was given a horse to get there.

I was in a vulnerable state for coming under kava’s influence that evening, having spent most of the prior week on the high seas, with minimal sleep and little to eat. That night a dream took me back to my boyhood on the family farm in North Carolina, where I had awakened one morning after a vivid dream of riding on a boat in a faraway ocean that was headed to some exotic and remote island. When I awoke, I realized that my dream within a dream was my current reality.

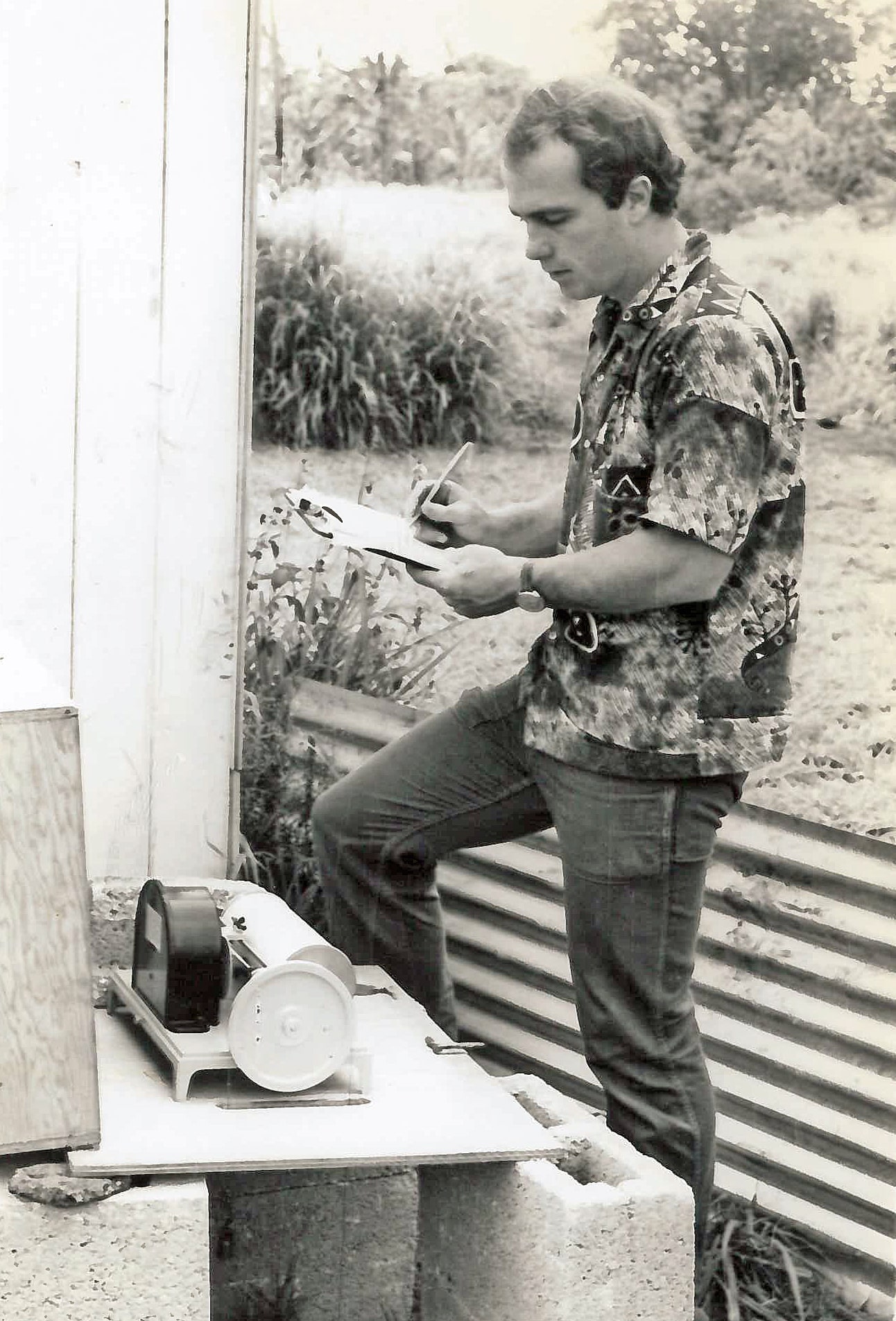

At daylight my host family served me a breakfast of breadfruit and coffee and led me to the horse. She was an old, swaybacked mare with a coarse blanket thrown across her back with only a bridle and reins. I rode her to the farthest village. Then we worked our way back to our starting point. I took measurements and I tried to explain the nature of my work to school children who at times gathered around me.

The closer the old mare and I got to our starting location, the more eagerly she anticipated the end of our ride. By the time we hit the home stretch, she was galloping while I was holding on for dear life and providing knee-slapping entertainment to every roadside onlooker. The horse’s timing turned out to be good, for by the time we returned, the ‘Ata’s passengers were already starting to board. I was rushed to the landing in the bed of the island’s only pickup truck and soon found myself on the boat once again, preparing for its week-long run back to Nuku’alofa.

I fell asleep on the ‘Ata’s top deck when I was roused by a sudden storm that sent seawater crashing over the boat’s gunwales amidst a deluge of rain. I was drenched and I stumbled in my flip-flops to the cargo hold where I wedged my body between burlap bags of copra and later to the galley where the crew had gathered. We passed the night harmonizing to old Tongan songs until daylight. They shared their breakfast with me and it was one of the best bonding and memorable experiences of my two years in Tonga. I wrote a report of my findings and it made its way to USAID and with programs from Australia and New Zealand, water supplies were improved throughout Tonga. Fast forward to the present, the Friends of Tonga network of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers recently funded a new rainwater catchment program using fiberglass cisterns for buildings and houses with metal roofs, which most homes in Tonga now have. My Peace Corps service taught me that the oldest and simplest technologies are often the most appropriate, a lesson I have applied often in my civil and environmental engineering career.