Early in the morning the roosters begin to crow before first light comes. This is the “madrugada” – the time of day when the men with their machetes head out for the campo. On this day we two Peace Corps volunteers will also head out of the village, to the city, going to a meeting and to check on the town’s only refrigerator for keeping medicine at the hospital for my health project. Somehow though absolutely essential, it has never been repaired nor made it back to the village.

Thinking about a good meal in the city, we rise early at the first hint of morning light and eat a little day-old bread with a black cup of coffee and walk holding hands towards the outskirts of town to catch the bus to the coast. (The villagers who don’t know think we are a brother and sister as we have no children.) As we go by, first the cement houses with backyard stick fences and then the mud huts along the main road away from the center of town, the world comes alive with sound – children’s voices and babies’ cries, the soft tones of lowered voices and the cumbia music that will be blaring loudly on the radio out of every door later on. As we continue out of town, the sounds and smells of the fields and jungle fill our lungs and ears, we remember how we learned in training that Colombia had two seasons – one hot and dry; the other hot and wet. Soon it will be hot but for now it is the coolest part of the day. I am wearing a simple flowered cotton shift and sandals; my husband his Levis and cowboy boots. Anticipating insects, we have light long sleeve shirts covering our arms.

After a bus ride into town, we consult with Peace Corps staff and meet with the officials to see what is holding up the refrigerator and then pick up a few items to augment our “campo” (rural) diet. We find our bus in the market and board the bus for a trip home along with chickens and many people. We find our seats and then a heavy woman, old and very large with dirty fingernails, comes along and places a board between the two aisle seats with one hand and settles on it, her buttocks up against the person on each side of her.

The woman holds a bundle, which seemed to be more of a burden. Occasionally her flabby rough-skinned arm would come to rest on the volunteer’s knee. We share the load. I study her face and would vividly remember it for the rest of my life. The “Costenian” (Afro Colombian) woman’s face was not ugly. Her face was stern but not unkind. She held within it all that she had suffered. Her eyes were glazed with sadness and hopelessness. Her drooping neck and chin fell to her swelling breasts with exhaustion. Her dress had been new but those were other days. It was cut low but had a collar that exposed a hanky clinging there between her breasts. Her ears were pierced and her ear lobes seemed the only part of her that was slim and young with little dainty turquoise jewels; but their gaiety was in stark contrast to the preoccupied sorrow smothered deep within the figure. The feet were large and covered in part by chartreuse tennis shoes meant for a man.

Her bundle was well covered with a green and white towel. It was shouldered with strength and pride. At last a few tears escaped across the nose and down the chin to only be quietly wiped away upon the collar of her dress. The dust was thick on the road with an endless parade of bumps and lumps. The ride was eternal. At last the woman shifted positions; she hoisted her burden upon her shoulder taking care it stayed well covered. As she rose slowly I looked back at my companion and smiled. The encumbered woman pushed off the bus. As her foot left the last step and she hit the ground firmly, she threw back the top of the towel, which revealed the baby’s head. She began the whining chant of a woman who had lost her son. Other women took up the chant that met her cries, “Antonio Segundo Sanchez is dead!”

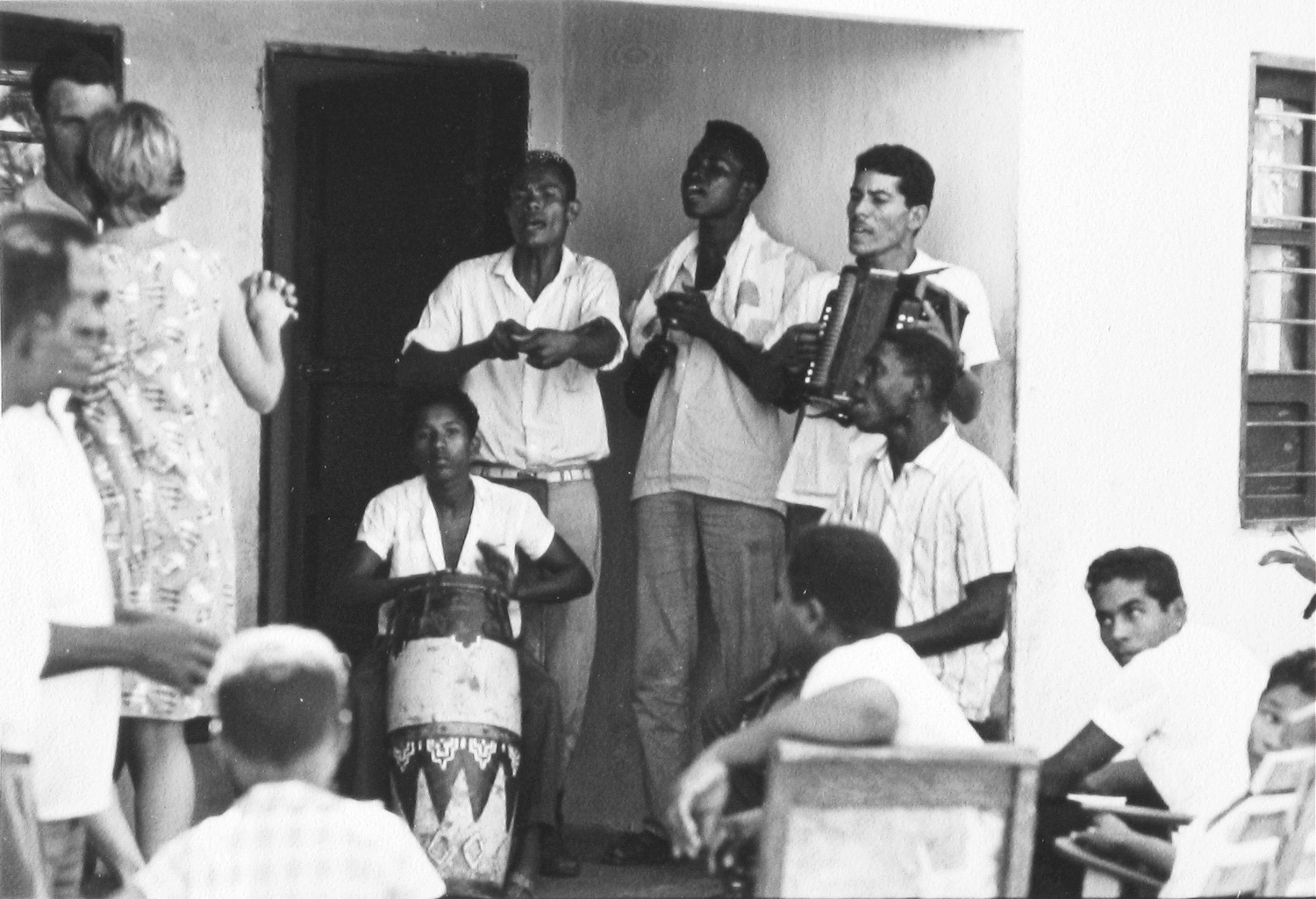

Janette was interested in Colombian culture and art, started a Hispanic Art Festival, and became an art professor in North Carolina with exhibits around the world.