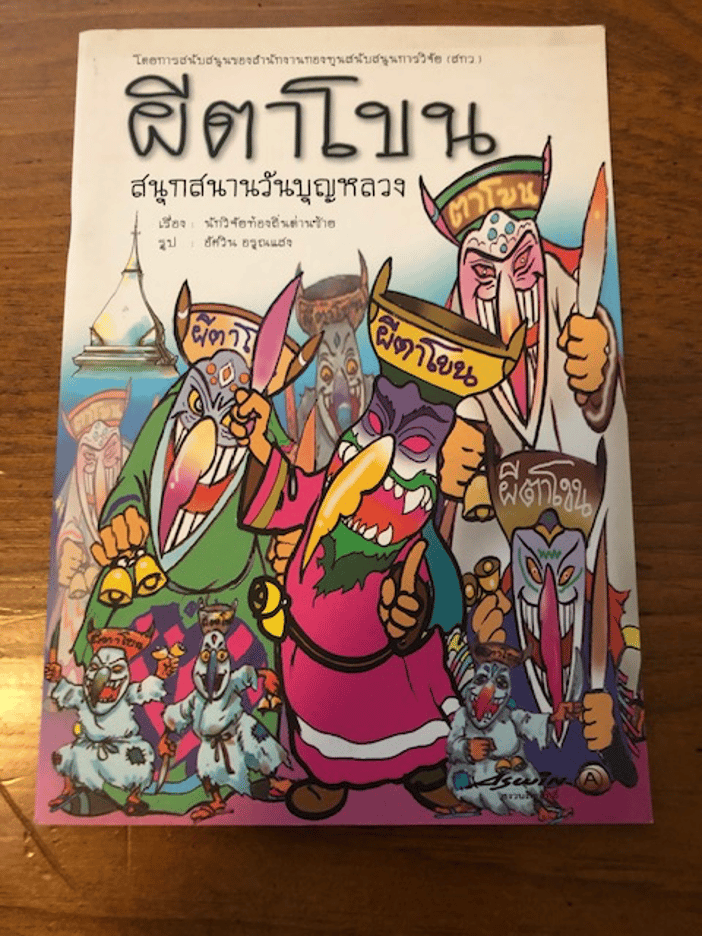

In Dansai, my students came to school in uniforms with their names stitched on the pockets of starched white shirts. They were incredibly polite – until one day shortly after I arrived at my volunteer site, they completely changed. They and other villagers donned ghost masks as part of Phi Ta Khon or Ghost Festival each June. These colorful masks and costumes transformed my gentle students from mere humans into ghosts able to communicate with the spirits essential to the village’s well-being. The masked ghosts invoke benevolent spirits to bring rain and fertility, necessities for a rice-based agrarian community. Without the intervention of these spirits, the people of Dansai believe that their rice crop will surely fail. Making their costumes and processing as ‘ghosts’ through Dansai was a highlight of their year.

The joyful procession of ghosts began at Srisongrak Chedi, a 16th Century chedi or Buddhist shrine built to reflect the close and enduring relationship between neighboring kingdoms that are now Laos and Thailand. This procession of ghosts was followed by a Bung Fai (or rocket-firing) event. Elaborately decorated bamboo rockets carried messages to the spirits and are believed to help spark much needed rain. The morning after Bung Fai, crowds gathered again at Srisongrak Chedi to make offerings to the monks, who chanted and offered sermons based on the dhamma—the teachings of the Buddha which explain that the essential element of life is suffering. The Buddha advised detachment to avoid such suffering. Wearing a mask to invoke spirits for rain was a world far from my roots. I grew up in a large Irish Catholic family with nine children (like John F. Kennedy, Peace Corps’ founder). I studied Theravada Buddhism in college and was an active opponent of the Vietnam War.

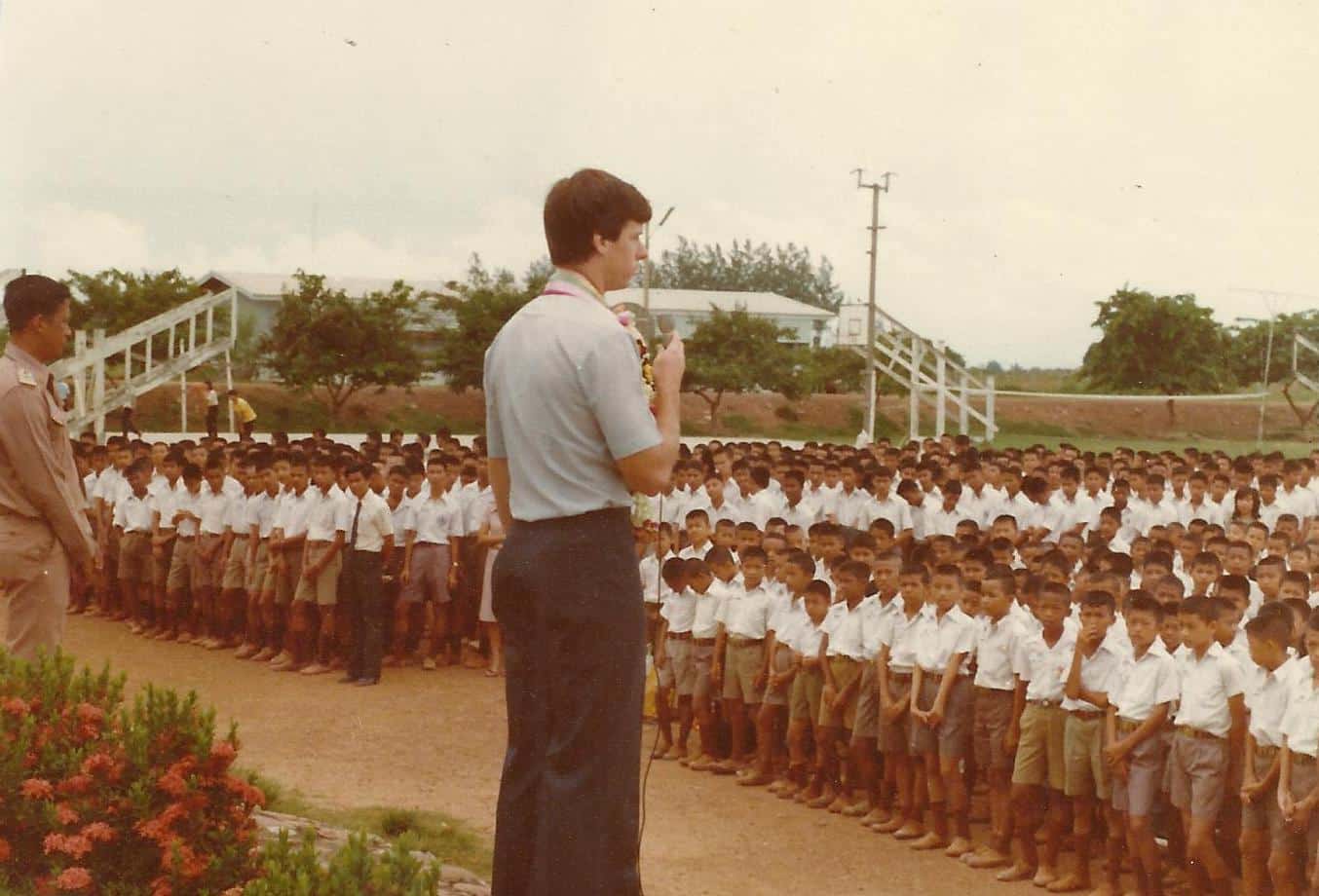

Students awake ghosts to nurture Dansai’s rice crop.

Before arriving in Dansai, I naively thought that I knew something about Thai Buddhism and how this war affected its neighboring countries. In 1975, the war in Vietnam and Southeast Asia may have been over for the United States, but the devasting consequences continued throughout Southeast Asia for at least another decade. My volunteer group arrived the year after the fall of Vietnam. At that time, Hmong and other Lao refugees were fleeing into Northeast Thailand. The Khmer people began to escape genocide in Cambodia. Dansai and the nearby Petchabun Mountains were still hot spots for an insurgency. After a military-led coup d’etat, students who opposed the dictatorship and American involvement in Thailand fled into the mountains; they engaged in low-level but deadly conflicts with soldiers from the Royal Thai Government. The practice of Buddhism in my village bore little resemblance to what I had learned from books. I expected to see the monks in saffron robes collecting alms on misty mornings, and home altars festooned with Buddha images, flowers and incense. I was surprised that villagers also had spirit houses strategically placed on their property. These were to placate various spirits and contained a mélange of Buddha images, statues of Hindu deities, guardian angels and pictures of ancestors.

In my studies, I learned that Buddhism teaches about moderation and detachment. Phi Ta Kohn was more about exuberance and indulgence. For religious festivals, my Thai neighbors dressed in elaborate costumes, prepared mounds of delicious food and made exquisite floral arrangements.

I came to understand that Dansai’s unique Phi Ta Kohn festival is an integral part of the cycle of seasons and a colorful admixture of cultural traditions and religious precepts. While the underlying beliefs are Buddhist, they include elements of animism, guardian angels, ancestral and natural spirits; essentially any spirits that might influence the villagers’ lives for better or worse.

More than three decades after serving as a volunteer in Dansai, I returned as the Peace Corps Country Director. On the surface, many things had changed: the insurgency had long subsided, the road to the provincial capital was paved, electricity had arrived, and classrooms no longer had thatched roofs. Dansai appeared much more prosperous than I imagined. However, the importance of the amazing Phi Ta Khon Ghost Festival had not changed. I am grateful to have been immersed in a way of life that gave my heart a second home, Thailand.