During my second year as a health educator in Aderbissinat, Niger, my partner and I had new saddles made for our two camels. The camels were our work transport, purchased for us by Peace Corps. There were no paved roads in the barren landscape around Aderbissinat, only tracks in the sand. Volunteers in larger towns got mopeds; we got camels. In addition to working in the village clinic, we would ride the camels several miles into the bush to visit nomadic Tuareg camps, where we would give nutrition lessons, check on pregnant women and newborns, and tend to simple medical concerns.

A tiny, windswept outpost on the Zinder–Agadez route, Aderbissinat was the most remote Peace Corps health post in Niger. The townspeople were mostly Tuaregs and Hausas, with a small number of Arab shopkeepers. Scattered throughout the surrounding area were the camps of Tuareg herders, who migrated seasonally with their camels and goats.

In Niger, leatherwork and silverwork are done by smiths called mekaris, who are highly respected for their artisanal skills. We knew of a mekari named Akou who lived in a tent on the outskirts of the village, and we went to see him. In our daily journal entry for April 9, 1977, we wrote, “Over the hill to see mekari about saddles and rings.” In addition to the leather saddles, we wanted to have silver jewelry made, and we agreed on prices for all.

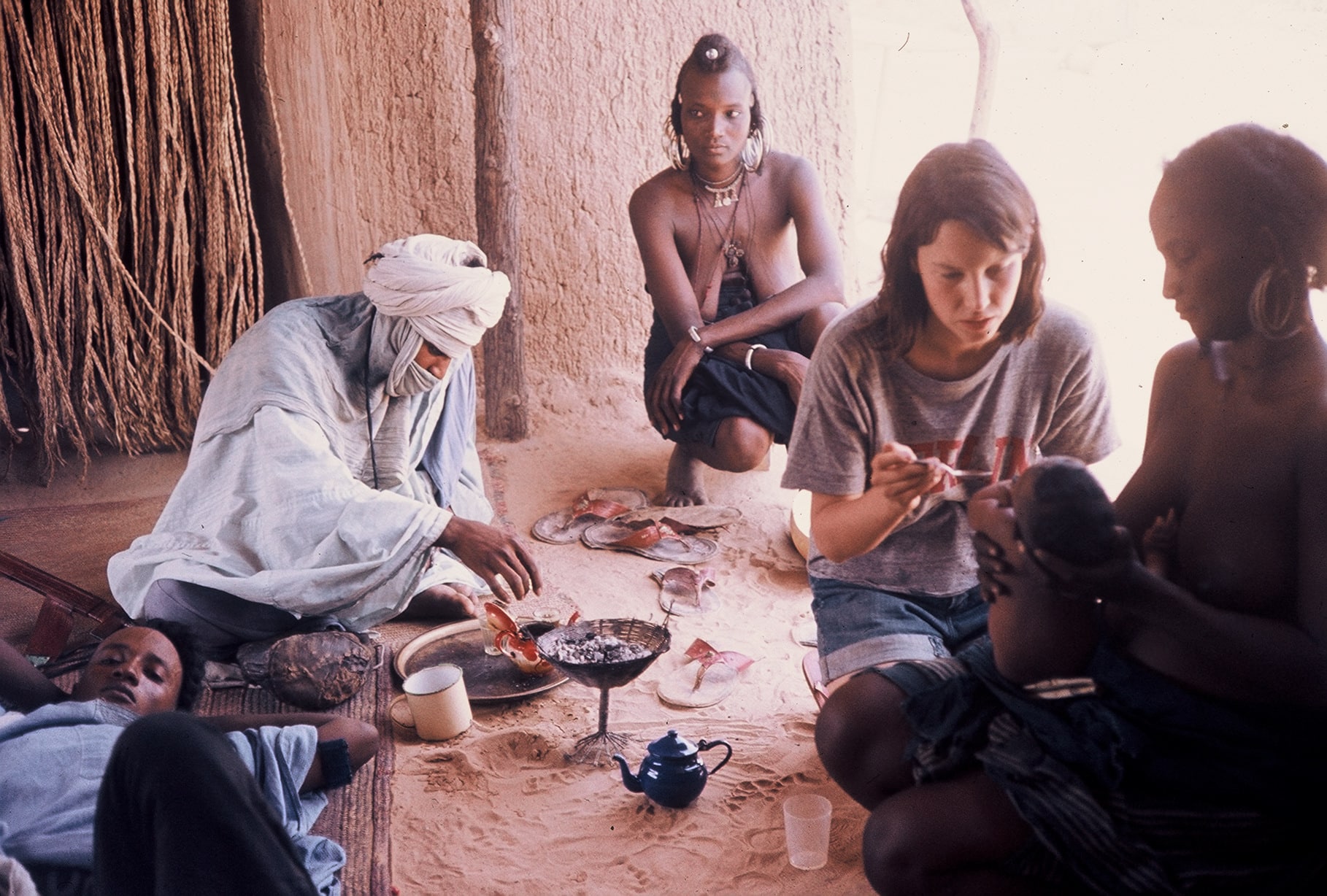

The work took two months, and during this time we made several visits to Akou’s tent. On one occasion he thanked us with a repast of macaroni and goat meat, special foods considered suitable for guests. And there was tea. Boiled in a teapot over a charcoal brazier, it was sweetened with chunks of sugar broken off a large cone wrapped in blue paper. Three rounds were served in tiny shot glasses: the first bitter, the second sweet, and the last sweetest of all. No visit to a Tuareg home was complete without it. On April 27 we recorded, “Tea, bread, macaroni and meat!! Saddles are coming along slowly, but beautifully.”

On June 1 we picked up the finished saddles, and several days later we tried them out – with unfortunate results. Our journal entry for June 5 reads: “Camel riding. We crash to the ground narrowly avoiding death. Saddle broken.”

This was in no way Akou’s fault. We were always falling off the camels. Highly intelligent beasts, they have a nasty streak and don’t suffer fools – inexperienced riders – gladly. My partner and I fell into that category, so they tossed us off. It was a long way down, but we were young and our bones not yet brittle. We must have had the broken saddle repaired soon afterward, because a subsequent entry notes that we went “to Akou’s to retrieve saddle” on June 11.

I didn’t bring the saddles home with me at the end of my service; they were passed on, together with the camels, to the volunteers who replaced us in the town. But I kept the ring, earrings, and necklace that Akou made for me.

The ring is silver, with delicate inlays of red and green glass. The earrings are slim silver hoops with geometric shapes at one end, and I wear them to this day. The necklace is made of silver tubular beads and black glass beads threaded together in an intricate triangular design. I have never worn it, in part because the cotton thread that holds it together is old and frayed.

The jewelry reminds me of how we gradually became part of the life of this tiny village on the edge of the Sahara. We commissioned goods to be made for us and sat in the silversmith’s tent, discussing our order in Hausa over glasses of tea. Above all, my silverwork reminds me of the mekari’s patience and skill and of the beauty to be found amid the vast arid scrubland of the Nigerien Sahel.