In the southern India state of Andhra Pradesh, the Peace Corps assigned 30 volunteers to promote school gardens. It turned out, however, that after all the training we received, the government wanted to emphasize nutrition and healthier food choices for school children. As we changed the program’s focus to nutrition, I had an idea: I could produce sets of silk-screened posters promoting nutrition and gardening to send to volunteers. I wrote a rationale for funding and sent it to the United Nation Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in New Delhi.

“Posters are a powerful means of influencing and promoting social action. Their value in Andhra Pradesh is that the great majority of villagers are illiterate. The mind can always grasp a picture when it cannot comprehend printed articles or remember long speeches. I hope that these posters will have an enduring impact on the minds of all the villagers.”

When I received approval from FAO, my first step was to take a 22-mile bus ride to the nearest city, Kurnool, where I purchased necessary supplies—drawing paper, artist brushes, colored inks, and the lumber and wood to build the screening frames and bamboo drying racks.

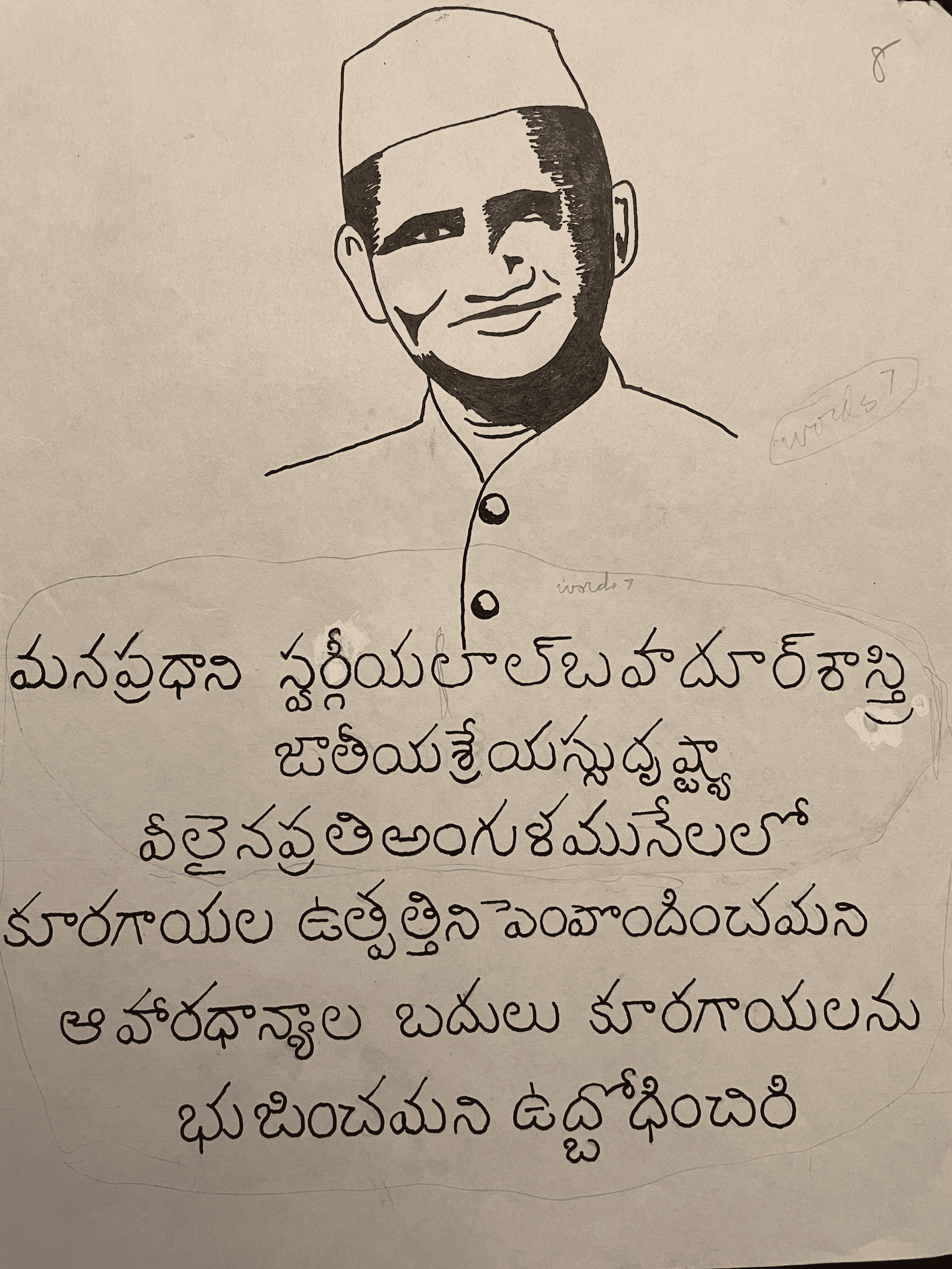

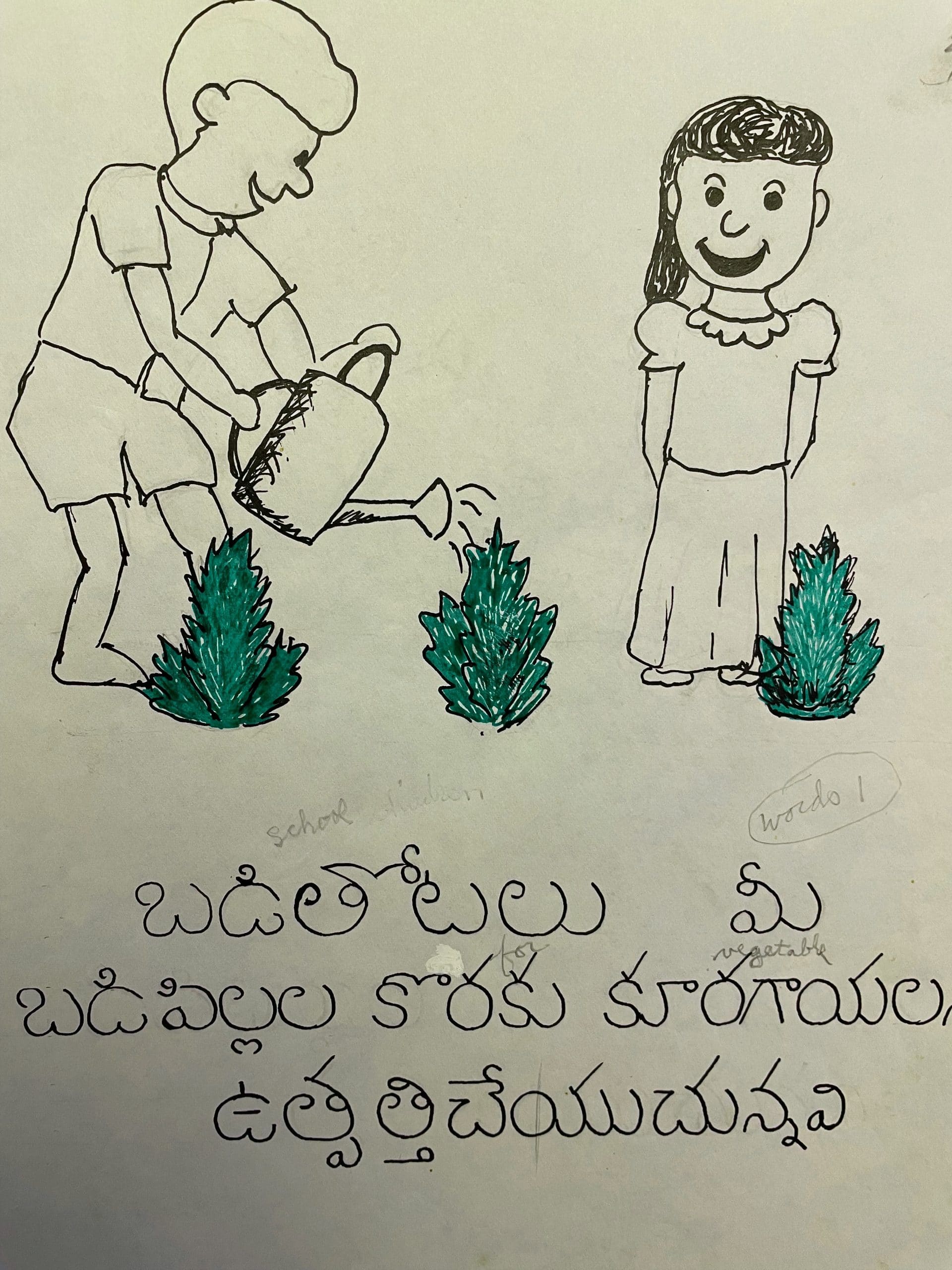

Then I drew caricatures of children and adults and illustrated vegetable gardens. One drawing depicted Lai Bahadur Shastri, India’s Prime Minister who briefly served between Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi. Local workers wrote brief messages in Telugu and I verified their accuracy with local village-level workers.

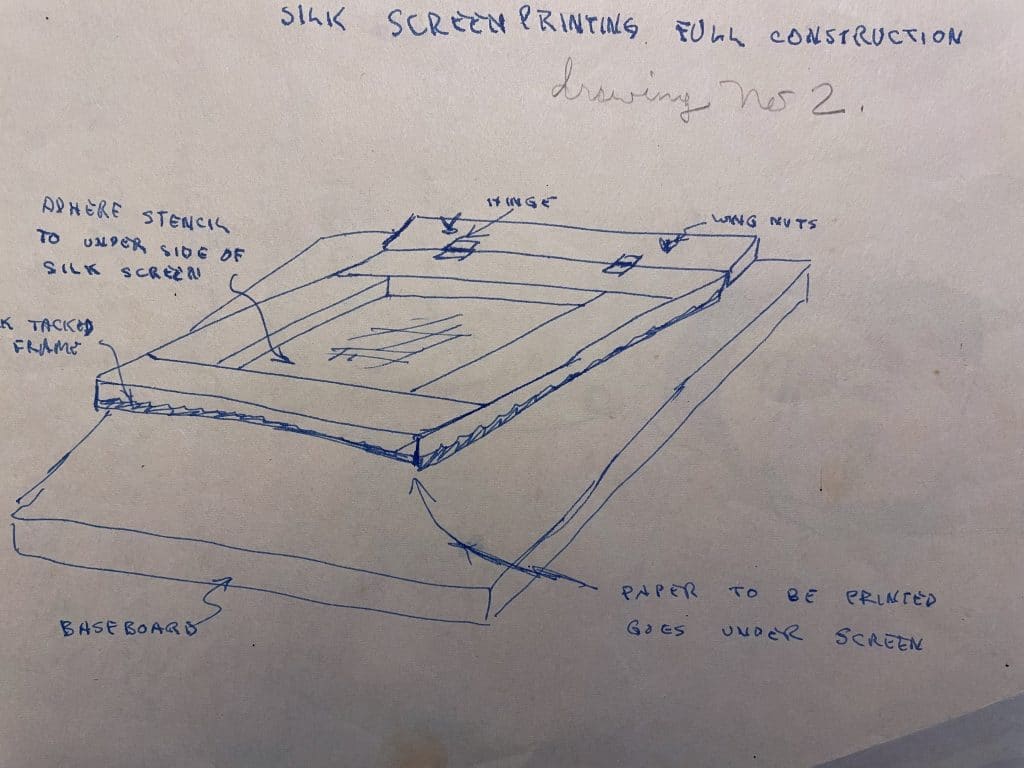

In my request to FAO, I explained the process of silk screen printing. It involves a mesh screen (in this case silk) which is used to press ink onto the surface of the poster.The artist creates a stencil and applies an emulsion with a small brush on the area that will not be printed. The emulsion generates an ink-resistant area and controls the colors during the printing process.

As an art major in college, I had learned how to do silk screen printing, but when I traveled to two universities in Hyderabad, I learned that silk-screen emulsifiers were unavailable anywhere. I would have to find a different way to apply an ink-resistant material to the screen.

A local auto mechanic helped me find a solution. I experimented with a gasket sealer used for plugging radiator leaks. It worked well enough to block the ink from passing through the silk.

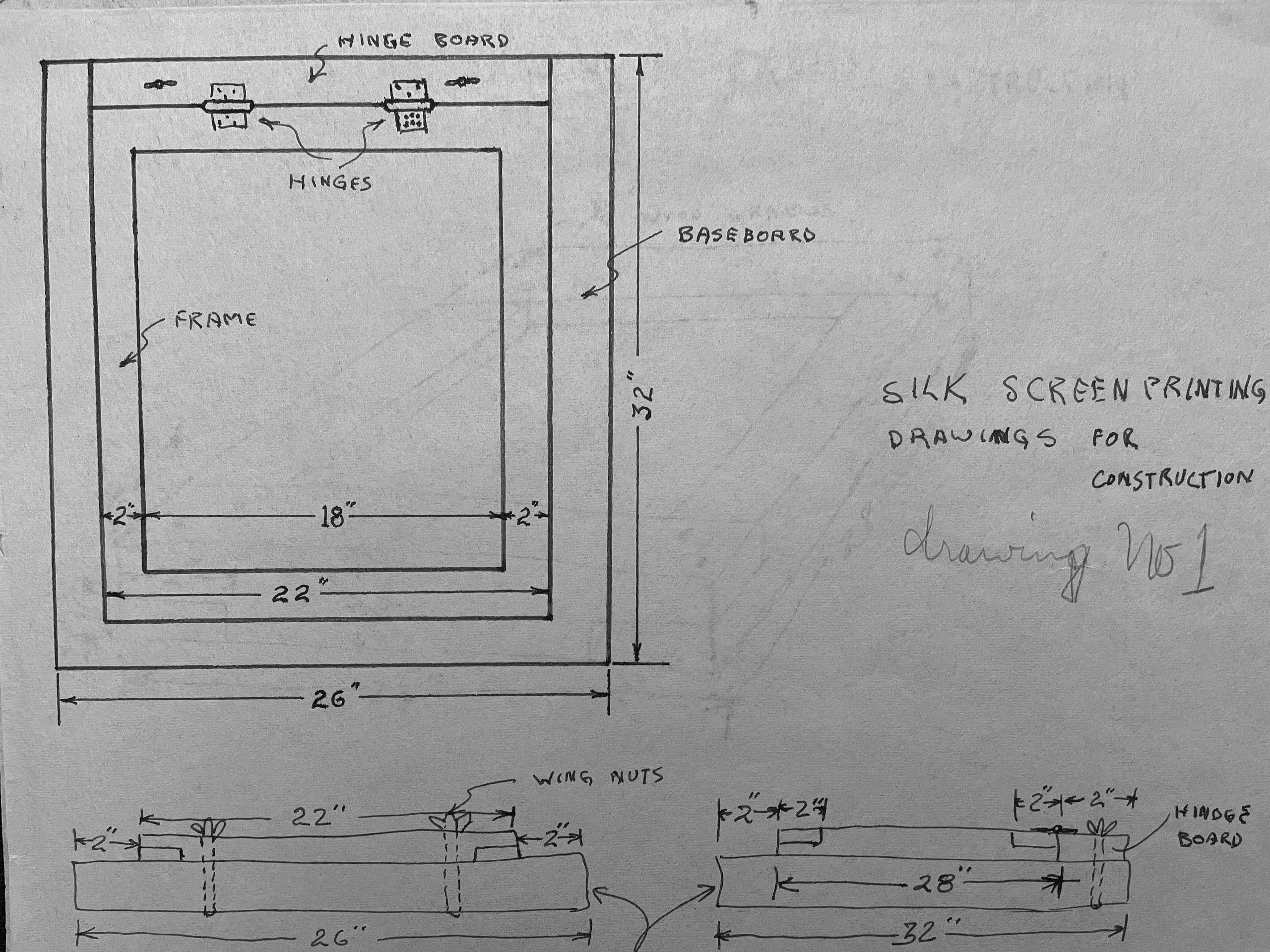

Another complication involved my colors—black, red, and green—which had to be applied separately to the posters and given time to dry. This meant that all 120 posters had to be printed up to three times and dried for 24 to 48 hours. The Kurnool woodshop built a hinged picture frame for the stencils and attached it to a board made to my specifications. I built a 6-by-10-foot bamboo rack, joined by twine to hold posters while they dried after I printed them.

Then I faced a different obstacle: I lacked the long, thin blade that artists use to spread ink over silk mesh, which forces the ink through the screen onto the poster. After more experiments, I fashioned a squeegee using a bicycle inner tube wrapped around three sides of the wooden blade. I could now print each poster two or three times using my improvised squeegee.

Spending four months to make drawings on paper and silk, spread emulsifiers, apply three different coats of ink with a squeegee, and drying each poster proved to be more time-consuming—but also more satisfying— than I expected.

I finished the posters and carried them off to the Peace Corps office in Hyderabad, 122 miles from my village. I did not keep copies of the posters for myself, however. I only saved sketches of my drawings, as well as my correspondence with the Food and Agriculture Organization.

In Hyderabad, the Peace Corps office assign me to a new task: drilling wells to pump water in Bihar, India’s drought-stricken northern state. I was no longer making posters, but I was happy because I was still a man on a mission.