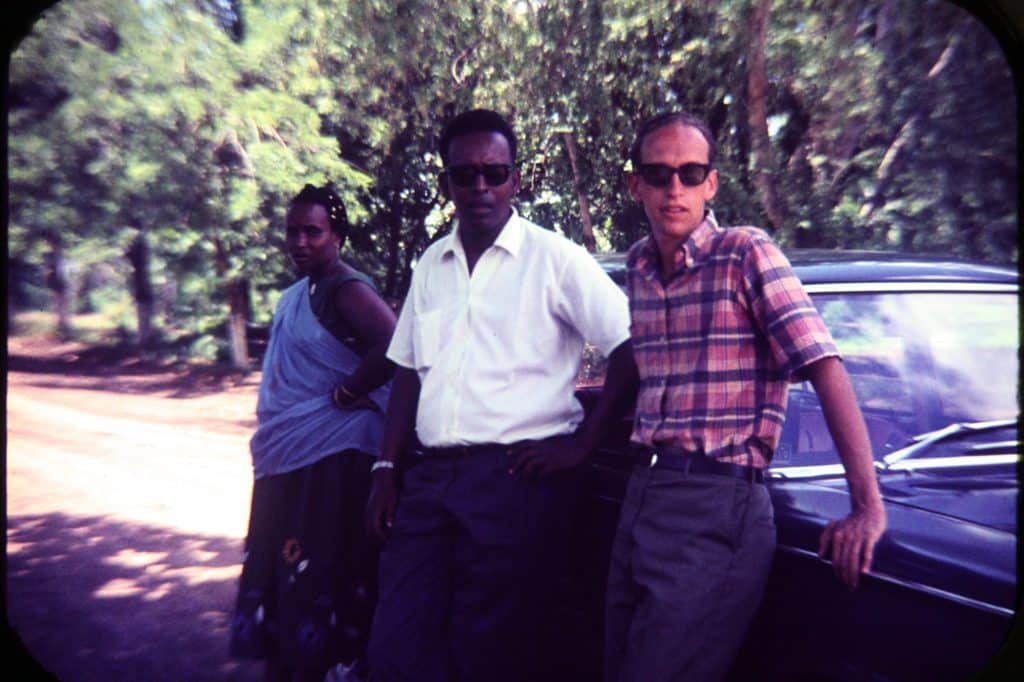

Our friendship with Abdullahi and Mariam began almost by accident. Abdullahi and I worked together at Police Headquarters in Mogadishu. One day, he asked if my wife Evelyn and I would teach he and his wife English in the evenings after work. We did so five days a week for almost two years. We focused on conversational English rather than grammar. Over time, while Abdullahi and Mariam learned English, we learned about Somali culture, the impact of Italian colonialism on Somalis in the south, and the continued Italian influence in newly independent Somalia. We learned deeper cultural lessons—the role of women in Somali society, the structure of Somali tribes, clans and subclans, the practice of Islam in Somalia, and of course, Somali politics.

When Evelyn and I left Mogadishu in May of 1968, our luggage contained enough Somali artifacts to start our own museum. Among other items, we brought home ivory bookends—a gift from the Somali National Police Force where I had worked for two years as legal advisor—two gumbaars (low wooden four-legged stools with stretched cowhide for seats), and a wooden tea set complete with carved images of Ethiopian soldiers shooting Somali nomadic women. Our artifacts also included a traditional headrest used by nomads, a wooden jug (weyso) for carrying camel’s milk, two camel bells, a large knife made from the steel of a Land Rover’s shock absorber, a varnished Koranic board with two Sura’s from the Koran written in charcoal, and numerous bracelets, jewelry, shawls and cloth given to Evelyn.

Most were gifts from Abdullahi and Mariam. Evelyn and I were not aware of this at the time, but more important than these material gifts was the greatest gift of all—their friendship. This bond spanned four decades and continues with our children and our children’s children. Our children grew up with an older Somali brother and sister living in our home. They have bonded with our Somali family and understand the significance of our Somali artifacts. These gifts will remain with our family. They are part of their heritage as well.

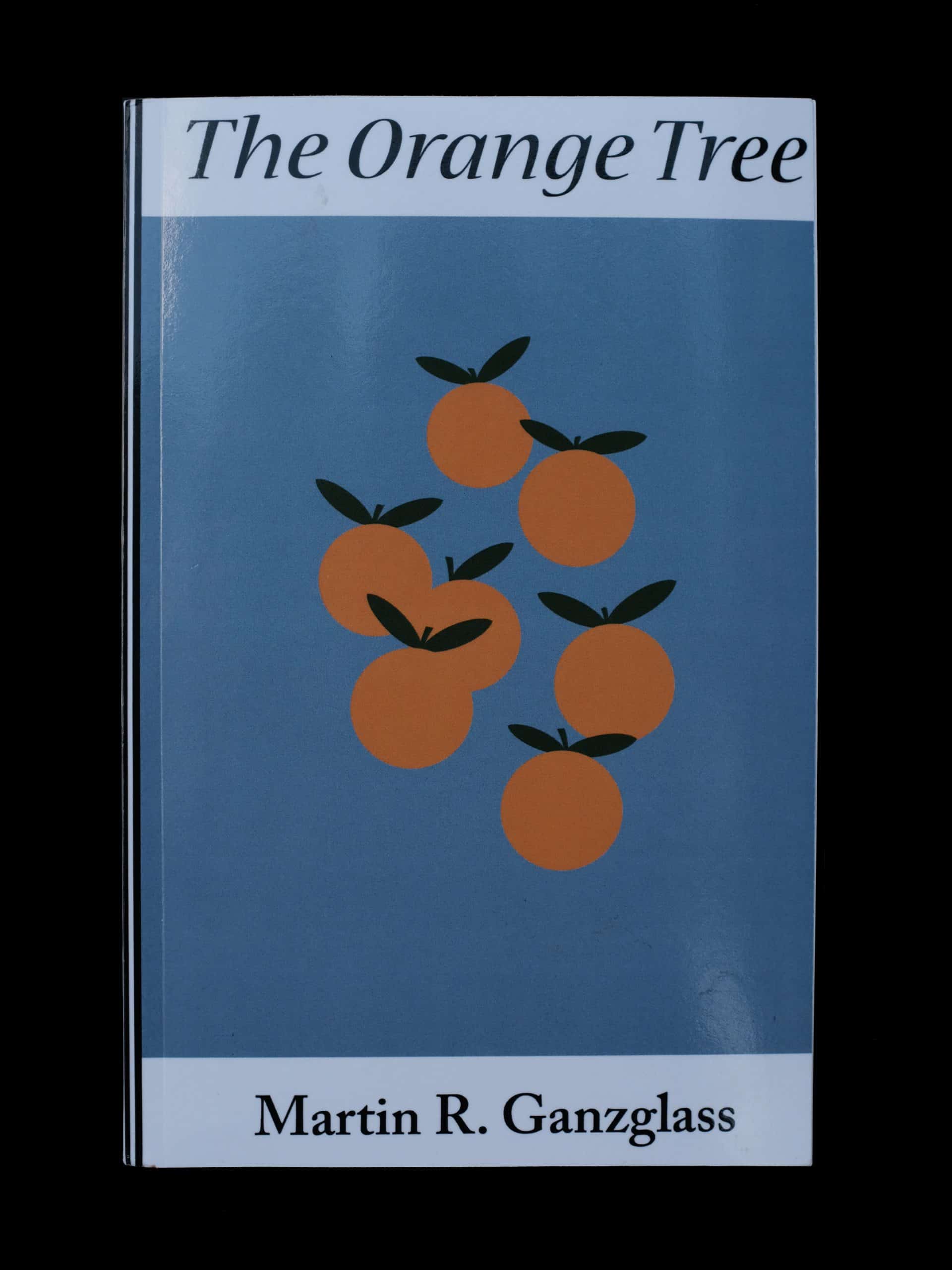

I have donated two books to the Museum. These are not artifacts in the usual sense. They draw on my knowledge about Somalia and the friendships that continued long after we left that country. The stories encapsulate the essence of a Peace Corps Volunteer’s service—to experience another culture and to bring that experience back home.

Time has not been kind to Somalia. In 1969 there was a military coup followed by 20 years of a brutal dictatorship, followed in turn by another 20 years of tribal war and instability. During the dictatorship, Abdullahi was imprisoned and held as a political prisoner, most of the time in solitary confinement. His oldest son and daughter lived with us in Washington D.C. and our children grew up with Somali siblings as part of our family. Then, in 1991 the dictator was overthrown. Abdullahi was active in efforts to restore a democratic government, but the country quickly descended into anarchy and clan warfare. The entire family fled Somalia and arrived in Washington, DC during the week of Thanksgiving, 1991. It was the best Thanksgiving our family ever had.

Over the years, our two families have seen each other frequently in the United States and Canada, something we never expected when we left in 1968. Our Somali family’s experiences in post-9/11 America became the basis for many of the details of Amina’s life, the Somali nursing assistant in “The Orange Tree.” Many of the tales in “Somalia-Short Fiction” are based upon knowledge gleaned from talking with Abdullahi about his youth and professional career, as well as my continued involvement and trips to Somalia in the 1980s and 1993.

The experience of Peace Corps Volunteers is as varied as the people who served. Mine turned out to have resulted in a lifelong friendship passed down to the next two generations. My two books are based on this friendship that developed improbably between a Jewish kid from The Bronx, and a Moslem nomad boy from the Majeerteen. Abdullahi would say that this was Allah’s will. I have learned not to disagree.