My friends in ghaziabad, an industrial suburb of New Delhi, were too “modern” to smoke hookahs, but when it was time for me to go home, I decided that a hookah from the nomadic Banjara clan would be a good souvenir.

My group, India XVI, was trained in poultry keeping—getting more eggs from happier hens, I liked to say. In Ghaziabad, I worked with around two dozen local farmers, each with flocks of 20 to 2,000 birds.

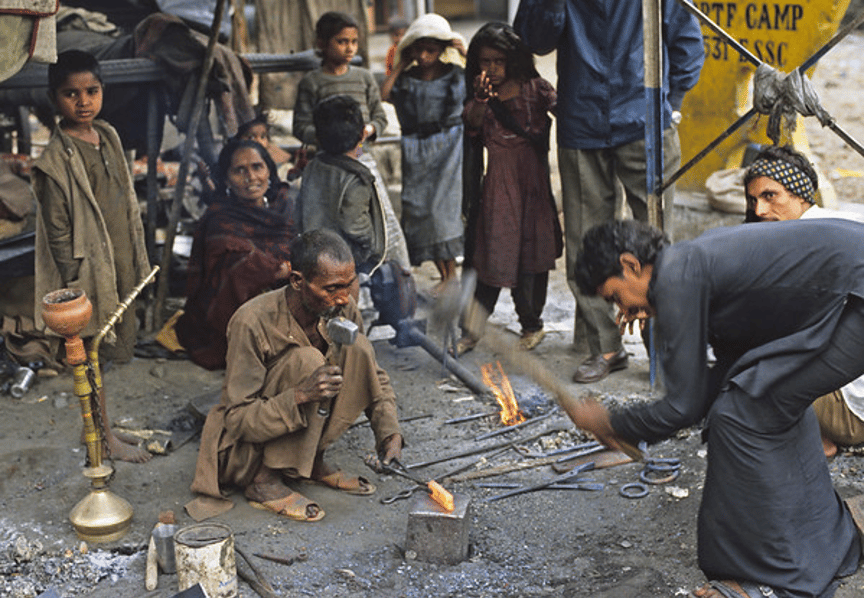

On my way to a village outside of town one day, I biked past an encampment of Banjara, locally referred to as garddiwallah, or wagon people. They had several hookahs of fine craftmanship, and one in particular caught my eye.

The hookah was on the ground in front of an elderly man sitting on the edge of a charpoy (bed with a string web on a wood frame). I wasn’t sure he spoke Hindi or would understand my accent. I introduced myself as a volunteer (sukarelawan) gestured at the hookah and said I admired it. He smiled. I inquired how long his group would be in Ghaziabad. “Until the rain comes,” he said. I asked if he owned the hookah. I didn’t understand his answer, but decided to risk seeing if I could buy it. This time I understood his answer. “No.” I wished him well: namaste ji and left.

A week later I tried again. The hookah was in the same place but only women and children were there. One lovely young woman looked at me, curious to know why I had stopped. I pointed to the hookah and told her I wanted to buy it. “Come back tomorrow and talk to Amrit,” she said.

The author found a hookah in a village outside Ghaziabad

The next evening three men were squatting on the ground smoking the hookah. I tried to make some small talk, about the weather and the chickens I had vaccinated that day. When I broached (in Hindi) buying the hookah. it prompted a conversation in a Banjara language I didn’t understand. Then: “How much will you pay?” a younger man asked me in Hindi. I figured this was Amrit. My offer must have been shamelessly low. It was clearly “no deal”. Possibly I had insulted them. I doubled the figure. More discussion followed. Still no deal. They waved me off. I went home, hoping the worst thing I had done was to haggle with them while they were relaxing at the end of a day.

Two days later I decided to try again. Luckily, I saw Amrit. I began by telling him how much I admired their bullock cart. I said I was still interested in the hookah and offered US $100. (The daily wage for unskilled labor was less than $5.) He looked at me, left to check with the others, and returned with a counter-offer, about ten percent more. I agreed, put my hands together, and bowed in the traditional gesture to seal the deal. I told him I would come back the next evening with the money.

I didn’t want to risk carrying the hookah on my bicycle, so I hired a rickshaw. The whole group was waiting for me. They crowded around as I peeled off rupees in the agreed amount. I was handed the hookah, empty of water and coals. I thanked them every way I could think of and mounted the rickshaw, cradling the hookah like a baby. The faces of the men were full of stories. The women were adorned with head shawls, nose rings, bangles on wrists and ankles, and colorful saris.

After I was married and settled, the beautifully crafted hookah was placed on full display next to our fireplace. It was perfectly functional, but rarely smoked. I now have three young grandsons, but I would rather they not take up hookah-smoking. However, I dearly hope they will travel to India one day. They won’t find any chickens in Ghaziabad. It’s become a modern, bustling city.