Within a few weeks after I arrived in Sagarejo in September of 2005, I began to feel very much at home. I was living with a wonderful family, learning a difficult new language, and teaching English to primary school children and local doctors. On the side, I helped secure books and computers for the Youth House library.

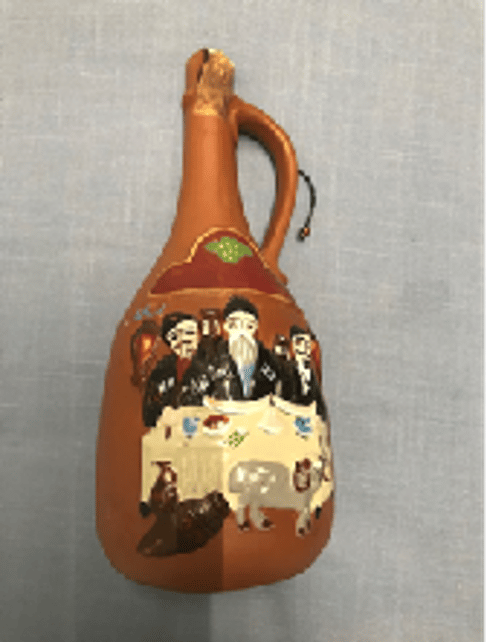

My family’s house sat amid lush vines of watermelon and grapes. Georgia is one of the world’s oldest winemaking regions, going back more than 8,000 years. Farmers still ferment grapes in large earthenware vessels called qvevri, which they bury in the ground until the wine ages to perfection. (In 2013 UNESCO added this ancient living tradition to its Intangible Cultural Heritage list.) Most families, like mine, grow grapes and make their own wine. And they still serve wine out of clay jugs, now popular in the tourist market. If these earthenware vessels distinguish the winemaking tradition in Georgia, the rituals around wine drinking are an even bigger part of Georgian social life. I especially loved the supper parties.

More communal feast than dinner party, a supra—meaning “tablecloth” in Georgian—might include family, friends, neighbors, or colleagues. It begins with the host laying a cloth on a table or on the ground and setting out abundant platters of food. Every supra revolves around multiple rounds of wine toasts. The designated toastmaster, or tamada, proposes the first toast and topic for discussion. Guests may respond, one by one, around the table. And then the tamada makes another toast, followed by more discussion, and the cycle repeats until late in the evening.

A Georgian wine jug made from clay

I attended many supras during my time in Georgia. They made me feel part of the community. One particular event stands out as a turning point—a birthday celebration for me hosted by my family early in my stay and attended by my Georgian counterpart, Sopiko. The conversation around the supra table that evening took a turn that would set the course of my Peace Corps experience.

I had an idea, which I proposed to Sopiko: why don’t we help renovate the obstetrics–gynecology wing of the local hospital? Badly in need of restoration and new medical equipment, it had received little attention during the Soviet era and none (due to the weak economy) in the 15 years prior to my arrival. What’s more, the project matched my personal interest in international women’s issues, especially around economic disadvantages. Sopiko took my idea to the doctors and they were on board. But they needed money. The hospital community was ready to commit to find funding for the renovation. And so was I.

The lead surgeon and I met regularly to plan what the U.S. embassy would later dub the “Grand Project.” I wrote a grant requesting funding to implement our plan. Our efforts paid off: Counterpart International, a nonprofit with offices in Tbilisi, donated $250,000 worth of slightly used hospital equipment, and the U.S. State Department awarded $10,000 towards the renovation.

Suddenly everyone wanted to help. Life in Georgia could be grueling, with unemployment at 80 percent. Chechnyan rebels had cut natural gas pipelines between Russia and Georgia, forcing people to use firewood for cooking and heat. My Georgian counterparts came together, working cooperatively to help each other. Community organizations in Sakartvelo and government offices joined forces to complete the project in fewer than six months, a remarkable accomplishment.

At an event to celebrate the success of this grand project, the U.S. ambassador lauded the exemplary collaboration between a Peace Corps Volunteer, who had come up with the big idea, and the local organizations that had worked so hard to realize it. The new hospital wing—equipped to ensure the safe delivery of babies and protect the health of all women in the community—now plays a role in safeguarding the promise of Georgia’s future.

I learned that change is possible if you believe in an idea. And so, in keeping with Georgian tradition, I propose a toast to all those who will take their seats at a supra table one day, especially young women, and engage in open and equal exchange of grand ideas that lead to creating more positive change.