I was doing relatively well as a university-educated African American. I had stayed connected to my old neighborhood by playing basketball and getting my hair cut on the weekends. During the week, I would drive to work in white shirt and necktie. In the mid- 1990s, I decided to resign as an IBM Systems Engineer to join the U.S. Peace Corps in Nicaragua. I was burnt out from the daily corporate grind. Interesting were the ”I don’t believe you” reactions on the faces of family and friends when told of my decision to accept the Peace Corps assignment. Why would I give it all up to go live in a Third World country?

I explained that I would be helping other less fortunate people, obtain language skills, and a different perspective on our world in exchange for my time and talents. I had realized the perspectives I had from my ‘hood and the corporate environment were limited. I recalled a sentence from the book I Wonder as I Wander by Langston Hughes that had once caught my attention. While in France, Hughes wrote, “My interests had broadened from Harlem and the American Negro to include an interest in all the colored peoples of the world – in fact, in all the people of the world, as I related to them and they to me.” I desired that kind of perspective.

In Nicaragua I was often mistaken for a native from their Caribbean/Atlantic coast regions. People didn’t notice me walking through outdoor markets or in less-developed barrios. I got relatively good prices on goods, services, and taxi fares. In general, the people I met were surprised when I revealed that I was born in the United States, as were my parents. The downside of being perceived as a native Nicaraguan was that many times I would be given special attention by security guards at the hotels and business establishments catering to foreign tourists.

I welcomed opportunities to dispel stereotypes about racial minorities in the U.S., especially to those in rural areas lacking access to responsible Western media. The bigger challenges for me were culturally based. Exposure to Mexican culture in California aided my adaptation to the Latin/Mayan culture of Nicaragua’s Pacific coast. It took some time to appreciate merengue and salsa music that blared loudly in buses and taxis. I found something in the capital city of Managua that was totally unexpected and familiar. There was a park that had several outdoor basketball courts. On the courts, I met a few Afro-Caribbean or Creole Nicaraguans from a city called Bluefields who spoke a Jamaican style of English. They told me about club Mansion De Reggae that played calypso, soca and reggae music. It became my cultural haven in Managua when I wanted to get my groove on till the early morning hours.

I decided to visit Bluefields, on Nicaragua’s Atlantic/Caribbean coast. At that time, there was little tourist literature on the city, but what I read confirmed that it was the center of the Black Creole culture in Nicaragua.

I began my twelve-hour travel to Bluefields perched on the edge of an aisle seat in an old school bus crammed with people, luggage, furniture and chickens. My trip’s final leg concluded with a two-hour ride on a small, single-engine panga (canoe).

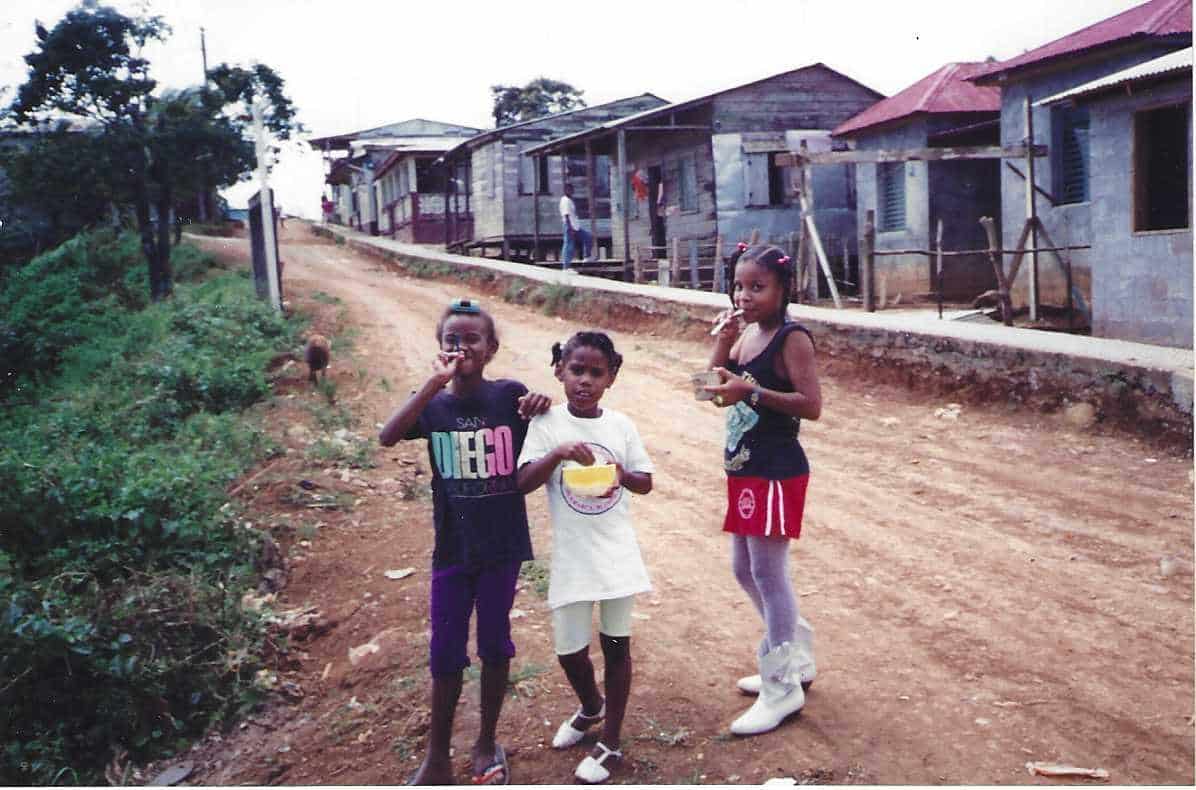

I was not surprised by the humidity of Bluefields, but disappointed that I heard few people speaking Creole English. Spanish was the language of commerce. After checking into a hotel, I set out to find the Creole culture. There were hints of Afro-Nicaraguan culture downtown as some storefront signs were in English and vendors sold Bob Marley T-shirts.

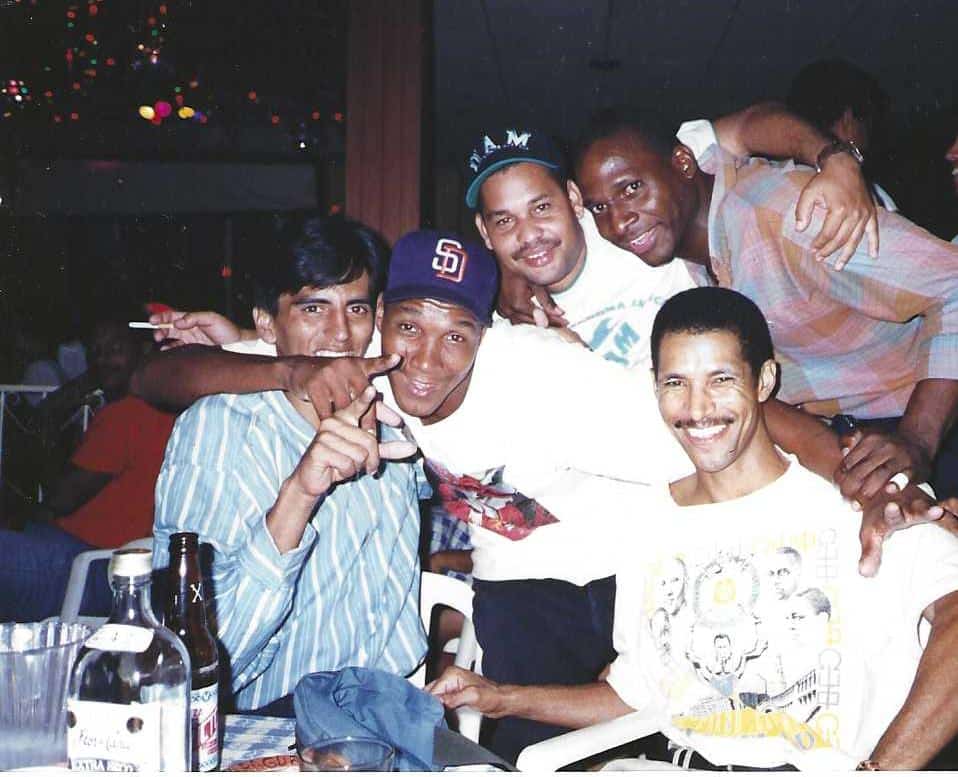

As I was walking I heard someone call my name. I turned around and saw Billy, a tall, light-skinned guy with a shaved head. I had played basketball against Billy in Managua. In Creole he said, “Hey mon, wha ya do err en Bluefield?” After explaining my purpose, Billy asked me to follow him. He led me off the main street to a restaurant where I met his friends. They all spoke Creole! After finishing their beers we walked to a section of the city called Beholden.

They introduced me to their world through food, music, and conversation on the history of Bluefields. They told me some of the Creoles in Nicaragua migrated from neighboring Caribbean islands. Some are descendants of slaves, and others of the Garifunas (Africans who were never actually enslaved).

After a few rounds of rum and coke on his porch, Billy asked if I wanted to go to a club he claimed few people from outside Bluefields had ever visited. There was a warm ocean breeze as we walked on dark, narrow streets, and between several small houses built on stilts, until I could hear a faint melodic reggae beat. We arrived at a large gazebo, also supported on stilts, that housed a dancehall called Lego-Lego.

By the shadows cast from a strobe light it was full of people dancing. We were greeted by several guys who were curious about me. My association with Billy was my passkey to that exclusive social spot. I spent the night dancing and sweating until sunrise.

I felt accomplishment in adapting to Nicaragua’s lifestyles including the Caribbean culture even though it is becoming diluted today. As a mature RPCV, the internet gives me exposure to various lifestyles throughout the world. But nothing is like the real-life journey and adrenaline rush when making decisions while exploring a new culture.

Note: In 2008 Lewis received the Franklin H. Williams Award to honor returned Peace Corps Volunteers of color who continue the Peace Corps mission through their commitment to community services.