It is one thing to be stationed in a barriada (slum) outside a capital city. At least you do not lose complete contact with the “modern” world. It is quite another to find yourself days from “gringo” tracks and years from modern civilization.

Recently, my volunteer partner Roberta and I had the opportunity to experience this striking contrast between new and old, developed and under-developed. Our assignment with USAID’s Alliance for Progress was to deliver and establish “little libraries” to the indigenous communities in the Sierra, and so, suddenly, within hours we found ourselves transplanted from hustling, bustling Lima to the neglected department of Apurimac.

Apurimac is a department in southern Peru – a region scattered with thousands of tiny Quechua Indian villages with tongue twisting names like Huancabamba and Huancarama. This region of the Andes Mountains has an average altitude over 10,000 feet and it is bitterly cold most of the year. Agriculture is the chief source of economy: one rides for miles through breathtakingly beautiful countryside which is dotted with small huts where the people live and eke out a meager livelihood. The owners of large plantations bask leisurely in their red roofed homes surrounded by plenty on their thousand-hectare estates which are tilled by the peasant farmers whose average daily wages is between 20 and 30 US cents.

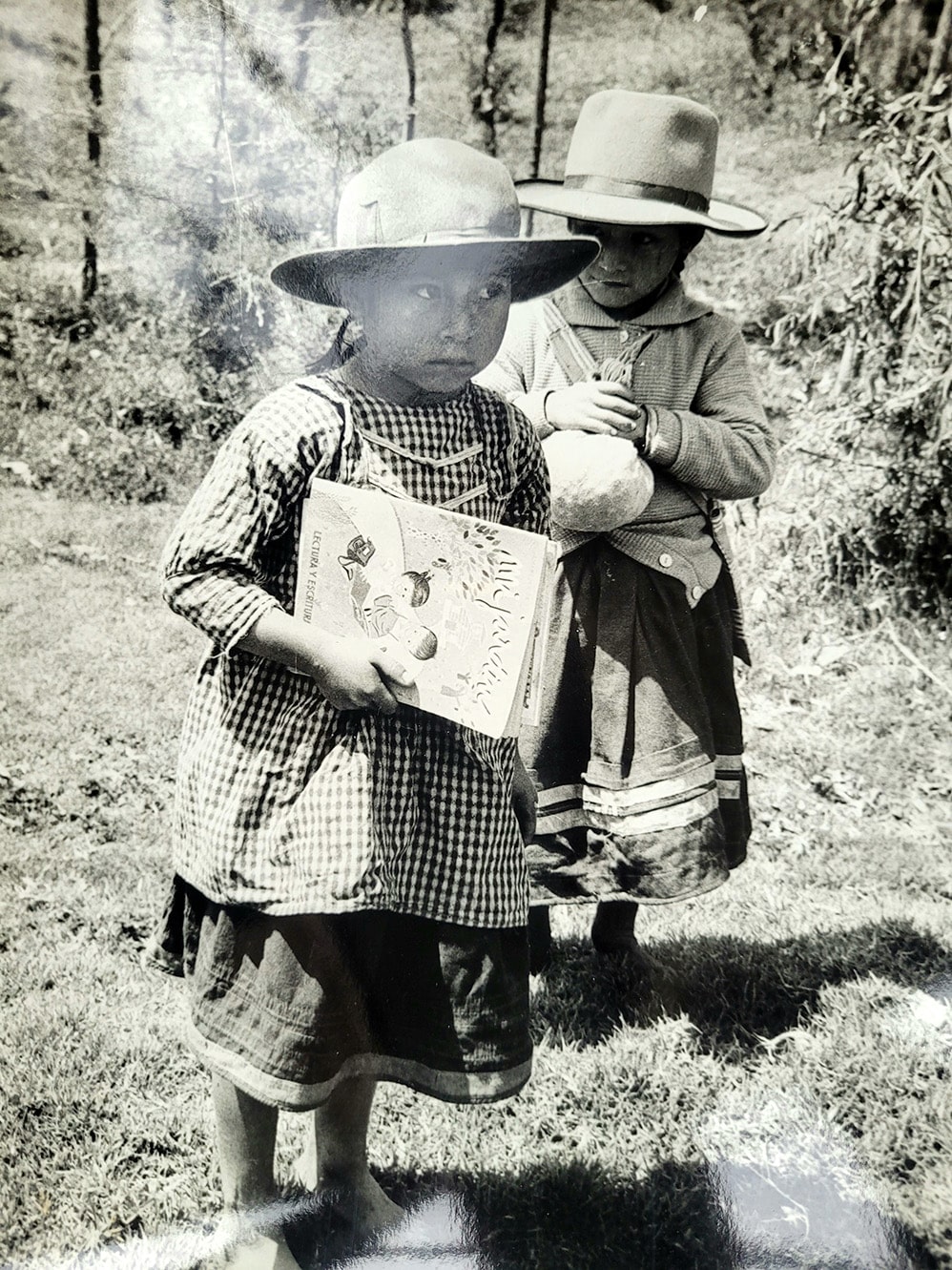

There is a certain deceiving calm in the Sierra – we could hear ourselves breathe and the air in the crisp, sundrenched morning crackles and impressions are sharp and piercing, almost frightening. The calm is engulfed by a certain tension, however, a tension created by the injustice of the land and the contrasts of the country. The Indian farmers are passive on the surface – they live simply, learning and assimilating experiences from the only source of education available to them…nature. They have had enough experiences to realize that poverty is a relative term, not an absolute. The parents may feel that there is little hope for material improvements during their lifetime but will not accept the age-old traditions that demand the same existence for their children. They want help in helping themselves – not tomorrow, but today.

Our planned itinerary led us on every conceivable mode of transportation. We arrived in Limatambo in the back of a transport truck which was filled with everything from chickens, vegetables and bicycles and, of course, several huge library boxes. From Limatambo we hitched a ride on a rather shaky bus and had a beautiful but terrifying ride to Abancay. Everywhere people were eager to understand our mission and the work of the Alliance for Progress in general. We spent hours discussing our aims and goals with them, as well as trying to give them a nutshell picture of “life in these United States”. Our stay in Andahuaylas lasted some three weeks, about twice as long as we had anticipated but then, time the Sierras is a foreign concept which has little meaning for the locals and soon had little significance for us either – “when in the Sierras, do as the Serranos”.

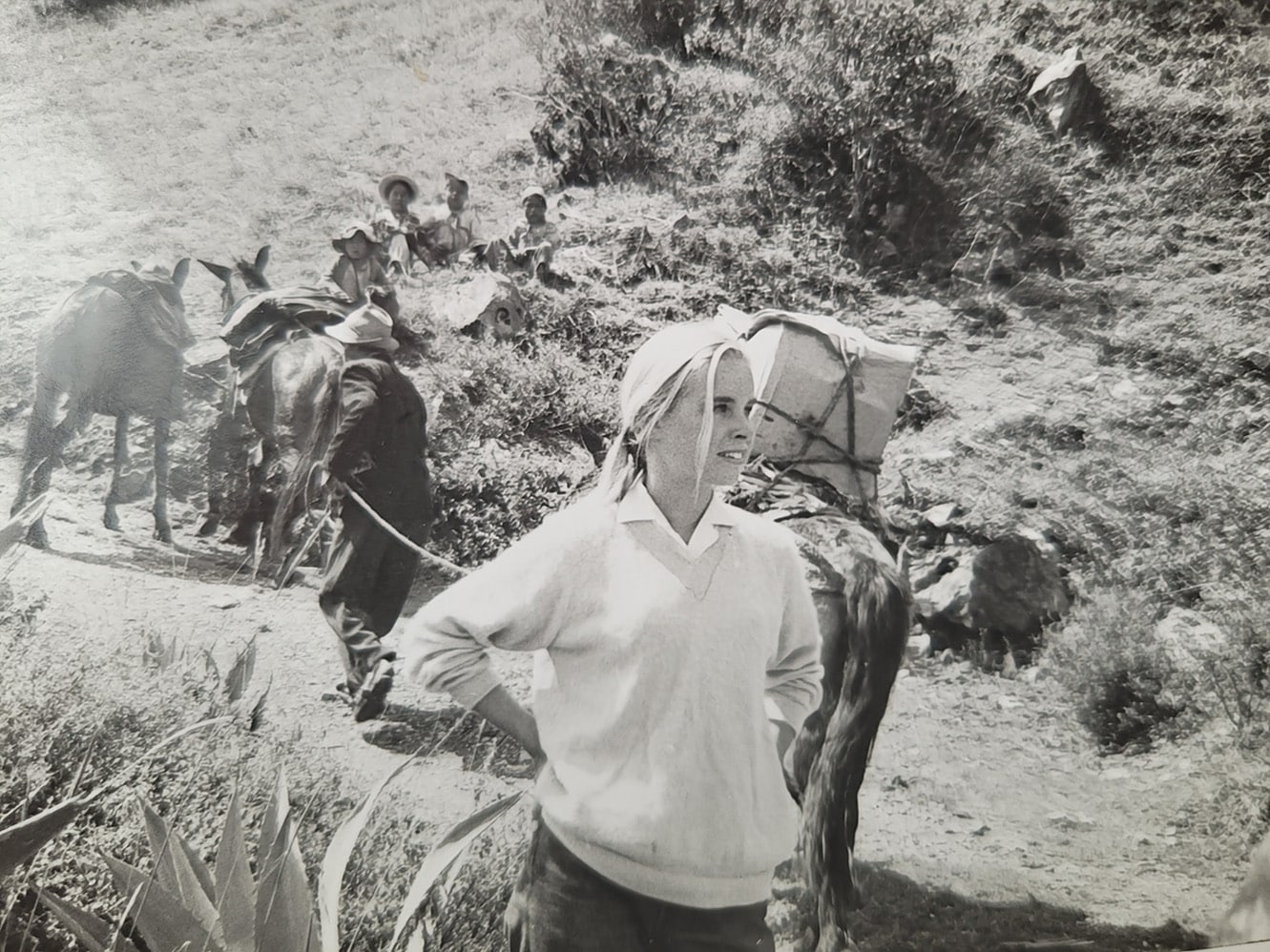

Andahuaylas, our base of operations, is a small community which looks exactly like every other town. It is centered around a plaza with a delightful old church on one side, the local government buildings on the other, and a small general store on the corner. It is filled with “local color,” that is, the brightly dressed women, shoeshine boys, street vendors, soothsayers and school children. We started off in the mornings on one or two day safaris to hidden away towns in which one loses touch with everything familiar, where cuys (guinea pigs) and cold boiled potatoes are considered gastronomic delights, where horses are of microscopic size and where strange words like “pa-ha-ren-can-ma” mean “see you tomorrow”.

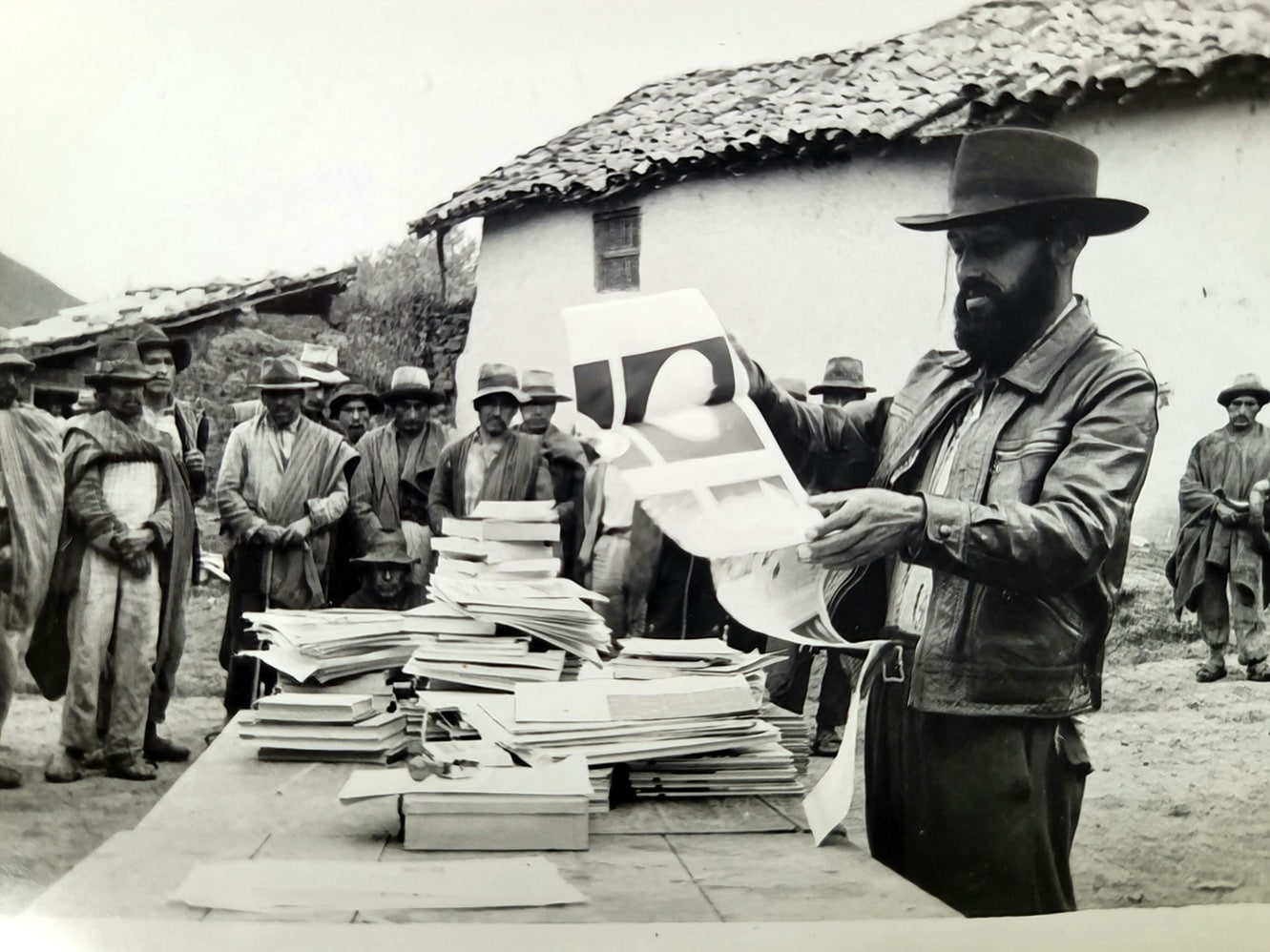

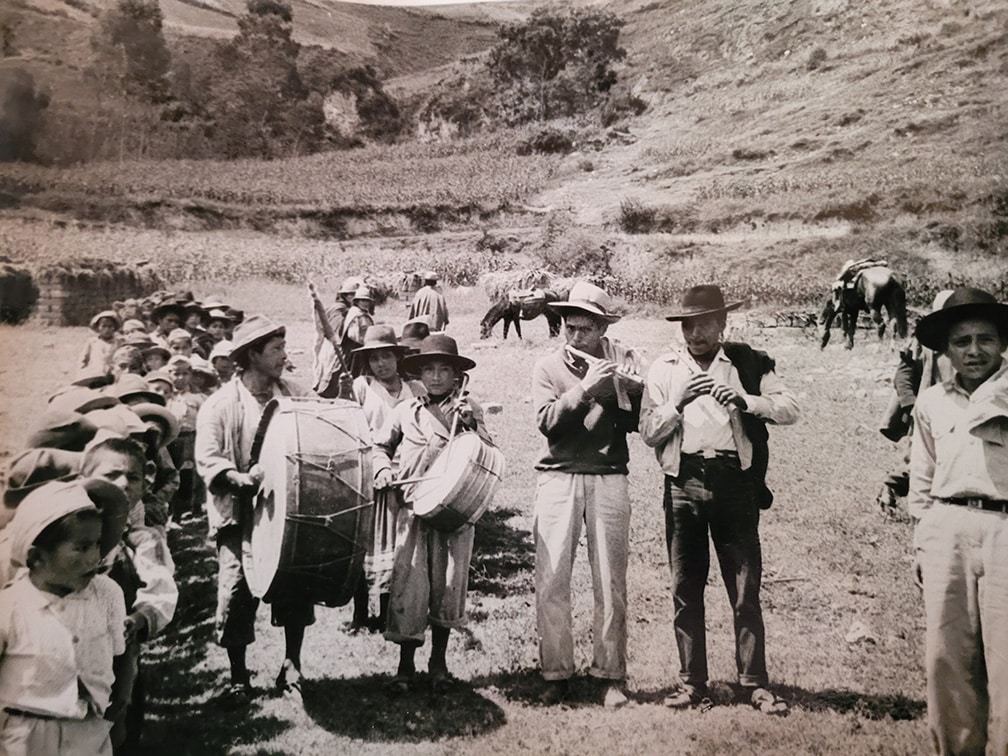

Our entrance into the towns were always amusing, as our visits were expected with great anticipation and preparation. We were met by townspeople dressed in their Sunday best, with flags and bands and great pageantry. They escorted us from the highway to the town, about three hours by horse. We were given the only horses in the community and were led to the tiny village. During the entire voyage, we were serenaded by a strange, loud band, and entertainment provided a festive atmosphere. When we arrived, a grand library inauguration ceremony was in store for us, again complete with entertainment, speeches, and handshaking. This was followed by a banquet in which we were served enough food for at least twenty people and in which the entire community watched to see our reactions to various choice dishes that were presented to us. These ceremonies were always good sport for both parties concerned, as I am certain that we greatly amused the campesinos by our strange dress and manners as did us by the same token.

Our trip led us to fourteen small communities and everywhere the people were extremely friendly and hospitable. It was with much regret that we left the peaceful Apurimac Valley and headed back to Lima, where life immediately took on a much more hurried, frantic tone. Our experience was quite worthwhile and the value of our contact with the communities immeasurable. Not only were the libraries greatly appreciated as a material donation and a prestige symbol for the community, but the very interest shown by the Alliance for Progress and the personal contact with “real people” from the U.S. was very meaningful to the people of these forgotten Sierra regions.

Amy D. Dooling submitted this story on behalf of her late mother, in honor of the transformative years she spent as a Peace Corps volunteer in Peru in the early 1960s.