Each school day in the town of Anecho began with our 400 students lining up in the quad outside their respective classrooms. Headmaster Etienne Adotevi or, on occasion, the duty teacher, would deliver the day’s announcements, the students would sing the national anthem, and then we would troop into classrooms for the day.

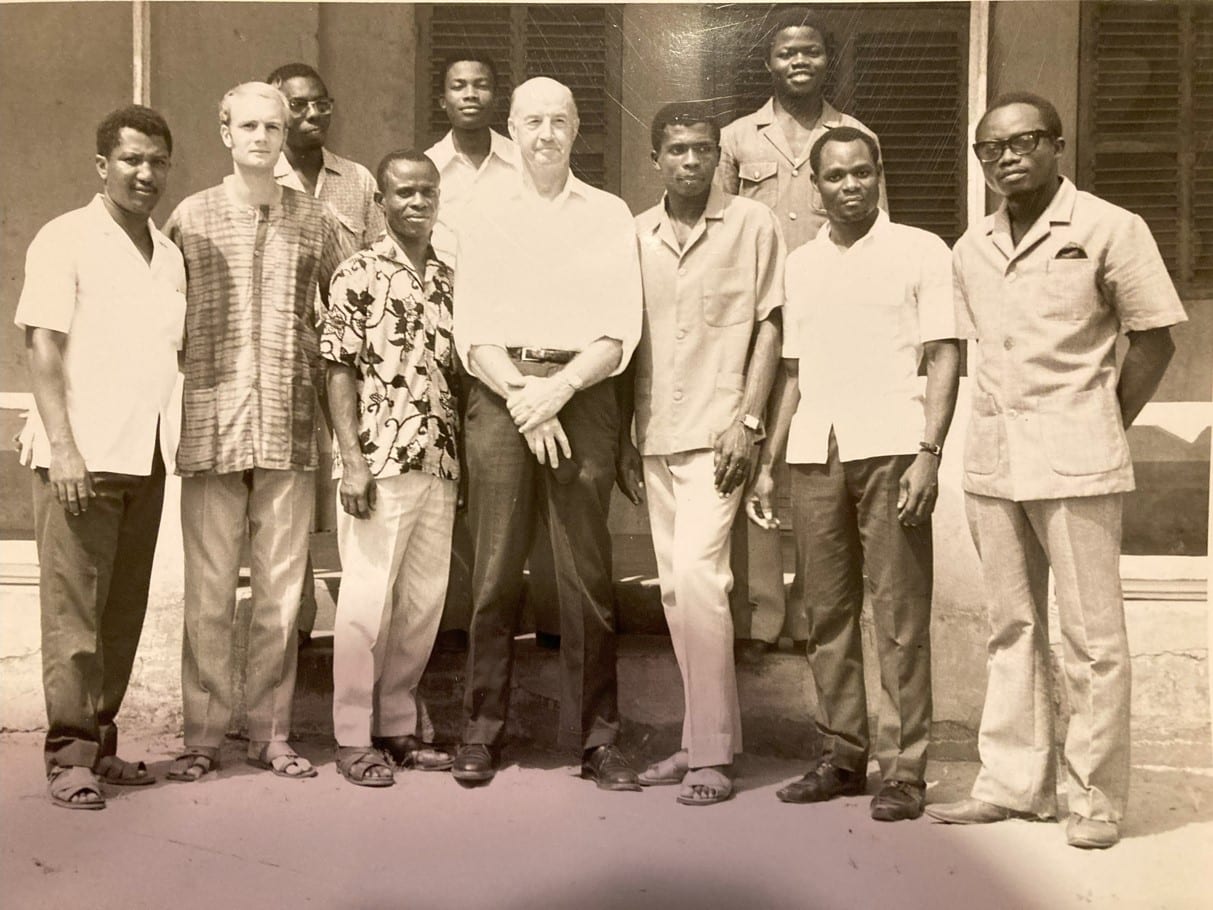

There I was, just over 21 years old and a few months out of college, trying to teach over 60 girls and boys crammed into each public secondary school classroom. There were four grade levels roughly corresponding to grades 7 to 10. I spoke English and French. They spoke French and a couple of Togolese dialects, Mina or Ewe. I was the only foreigner on the faculty of ten teachers. I never knew the ages of some of these students because birth dates were never recorded for those born outside of the town.

One morning about six weeks into my first year of teaching, I entered my crowded classroom and looked over to the right side of my cinquième class of 14- to 16-year olds. There in the third row was a student with his arms folded and his head down on his desk.

“What’s wrong with him?” I asked.

“Monsieur, il a mal au ventre,” several students volunteered. He has a stomach-ache. I continued with the lesson of the morning, and the student with a stomach-ache remained still with his head on his desk.

The next day when I came into class I saw that the desk in the third row where the student with the stomach-ache had sat was empty.

“Where is he?” I asked.

“Il est rentré au village.” He has gone back to his village, they told me.

So I went on with the lesson. At morning assembly a couple of days later the headmaster, Etienne, announced that the student had died. He somberly invited all of the students to reflect on “cette ombre qui passe chez nous.” This dark shadow passing among us.

In the faculty room a few days later Etienne told the faculty he would go to the student’s village over the weekend to express condolences to his parents. I decided to accompany him. The next day we rode our mobylettes along bumpy back roads and narrow winding paths about eight miles to a village of eight or 10 mud huts surrounded by fields of corn.

Etienne met with the parents, expressed the condolences of the school, and gave the parents about 2000 CFA francs––about 8 U.S. dollars—and equal to the amount the family had recently paid for their son’s yearly school fees. Together we then walked a few steps beyond the cluster of homes to a bare patch of ground in the fields where their son had been buried in an unmarked grave.

Arms outstretched toward the grave, the headmaster called out in Mina to the student. I didn’t understand what he was saying, but Etienne was speaking directly to him. What Etienne did has really stuck with me because as I stood next to him two thoughts came to me. I realized that the last thing our student had done on this earth was to walk the eight miles back to his village with a stomach-ache. Then I remembered two years earlier when one day on my college campus I, too, had had a stomach-ache. But as my own pain had increased I walked to the student health service and a few hours later I was in the hospital undergoing an emergency appendectomy.

Standing by a student’s unmarked grave in Togo I realized that I was alive and our student was dead because I had access to medical care and he did not. I think the reason I decided to go with Etienne to pay my respects was my belief that as a Peace Corps Volunteer I needed to let people know that I—and by extension my government and the people who had sent me to the school in Anecho—cared about them.

Last year I read a column by the late Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson in which he referred to service in developing countries as “the mission of defending human dignity,” and that in interacting with people there “. . .you will not only be finding ways to help them; you will find examples of how to be more human. They often provide a master class in living a life of purpose and dignity. In nearly every situation, I was the student, not the teacher . . .”

As I stood at that student’s unmarked grave more than 50 years ago I was the student, not the teacher. The stark simplicity of the events in that village and Etienne’s appeal to the memory of one of our students was a lesson in grace, in dignity and in compassion—a lesson in being more human.