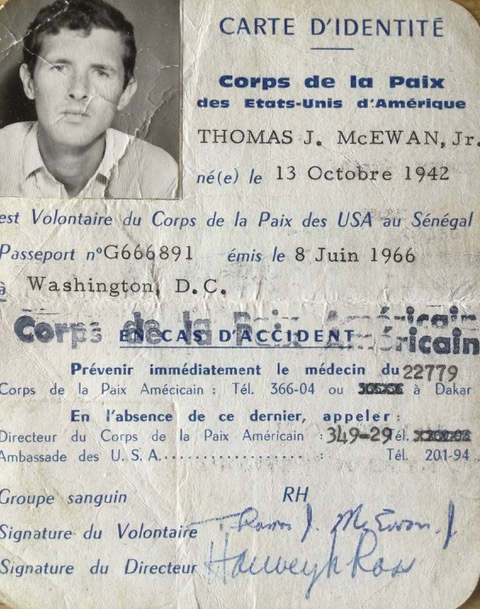

Journal entry, Bignona, Senegal, January 1967:

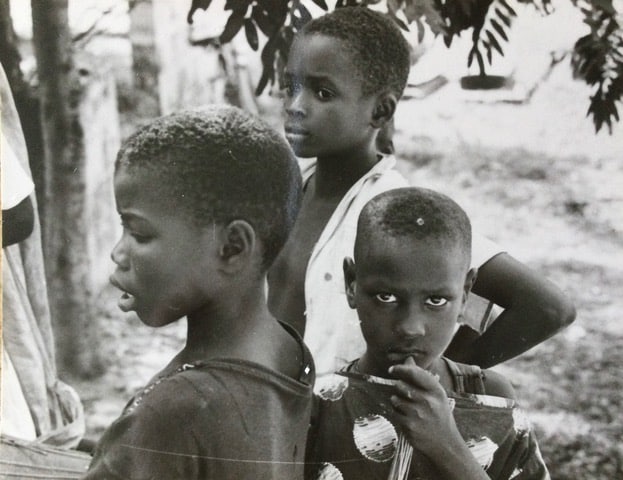

A few weeks ago, a little boy came over to show us that his wrist was swollen stiff. It looked like a broken bone, so we took him to the small local hospital. The doctor said that the wrist was indeed broken, so we left him to be cared for and tracked down his parents to give them the news.

It turns out that his parents immediately took him out of the hospital and left him in the care of the local marabout, a Muslim holy man, who proceeded to bleed him. When this did not seem to work out, the marabout broke another bone in the same arm, predicting that everything would now be just fine.

The story gets worse. After his time with the marabout, the poor boy was put under the care of the local traditional healer who proceeded to slice the arm open. It consequently got infected and remained that way for several weeks. The broken arm had swollen up to twice its normal size and he had no feeling up to his elbow. We, again, took him to the local doctor who told us that we had to rush him to the main hospital in Ziguinchor which is about forty kilometers and a long ferry ride away.

When we finally got him to the hospital, a nun balled out the kid for not coming in sooner. She was hell on wheels and a real piece of work. Between the marabout, the nun, and the healer, our little guy was really getting an excruciatingly painful introduction into the world of religion.

After the encounter with the nun, my Peace Corps partner, Bill, took the boy to see the hospital doctor who proceeded to give Bill holy hell because the wound was dressed poorly. He also added that Bill and I would have been more useful fighting the war in Viet Nam than volunteering to help the poor people of Senegal.

Bill and I returned to Bignona, but I do not remember seeing the little boy again. It seemed there was nothing more we could do.

___________________________________________________________________________

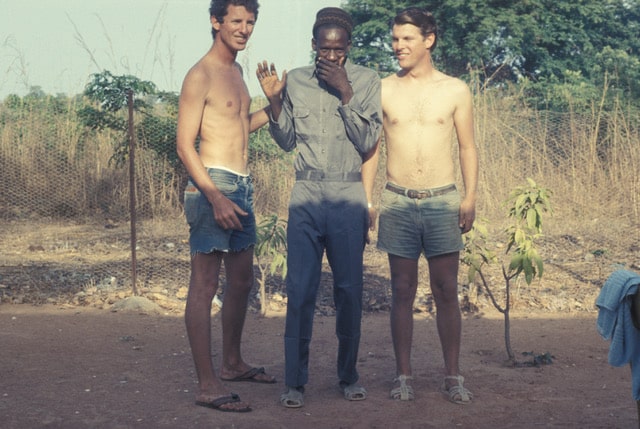

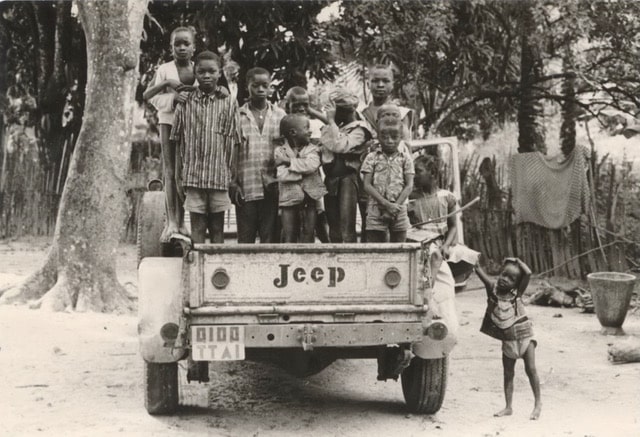

Upon returning to the USA, I was often asked what I did in the Peace Corps. I could not very well respond that I spent two years helping children with broken arms. In fact, we worked for a ministry of the Senegalese government called Animation Rurale. It was our responsibility to help organize the building of schools and the digging of wells and latrines in twenty-seven different villages all over the Casamance region in the south of Senegal.

The highly physical aspect of our construction work helps sustain a limited idea of what the Peace Corps experience is all about. The Peace Corps is, however, not only about spreading the Boy Scout creed and building schools made out of mud blocks and straw roofs. Just as the USA is not only about cowboys and shiny cars. These are only visible accouterments. They are not what is meaningful and important.

It is the day-to-day life that the volunteers live that is important. Life in Africa is like life everywhere. One works, eats, and sleeps. But we were doing this in a culture completely alien to the one I had spent twenty-three years growing up in. Simply stated, in Senegal I had to live my life on completely different terms.

A good example of living on “completely different terms” was trying to help out that little boy with a broken arm only to have his parents put his life in danger because of their religious beliefs. The subject of religion and its effect on people’s lives is certainly a subject for reflection. One of the problems with religion, from my point of view, is that it is so judgmental. So who am I to criticize those parents? The little boy was hurting, and they did what they thought best according to their beliefs.

Experiences like this (and they were many) changed me from a somewhat critical and cynical person into a more open and introspective individual. And since things moved very, very slowly in Senegal, I was obliged to become more patient and persevering . And my Peace Corps service certainly helped me become a more decent human being.

I am now eighty. When I stop and consider that only two years of my life were lived in Africa, it is amazing to think of what an influence this short period has had on my existence. I never went back to Senegal after leaving the country in 1968. As Thomas Wolfe so rightly said: “You can’t go home again.”