IN MY THIRD YEAR IN COLOMBIA, I joined the Oficina de Tugurios, the Slum Rehabilitation Office in Cartagena. The progressive director, Tito Bechara, had gathered a staff of Peace Corps volunteers to launch social programs. Liberation Theology was the rule of the day: priests were leaving Spain to introduce social change in the new world. Peace Corps volunteers were seen as a secular version of the priests’ attitudes.

For many years Caño Salado had existed along the Canal del Dique, a canal dredged by slaves in the 18th century. Monsoons often flooded canal communities and a severe 1967 storm destroyed Caño Salado. Residents fled to higher ground and invaded the vast lands of the Ospinas, a family of high status in Colombian society.

I was the only architect in the office so Tito sent me to work with the community on a rural new town. The people there called me Carlos because it was easier to pronounce than Earl. This community would change my life, as well as my name.

I stood with everyone in the smoke created to scare off the no-see-ems that plagued us at sundown. I slept on a door rigged up under a net for shelter. I bonded with Campos, El Mono, Compa’ Mañe and others who were now homeless. The community leader, Alfonso Perez Correa and I talked about creating a new town: Puerto Badel. It would be named after the then governor of the State of Bolivar, Sr. Donaldo Badel. Alfonso advised me to get married and explained the risks he had taken to become the leader.

I quickly realized that a social divide was firmly established. I was the gringo and therefore I had the right answers. All of my Saul Alinsky training about felt needs and participation had not reached Puerto Badel. Every time I asked the gang to tell me what they needed, they replied, “No! No! No! You know the best.”In frustration I drew up a sub-division design that might have brought cheers from my Washington University School of Architecture classmates back home.

Everyone gathered under the thatched roof of the meeting room to hear my plan for Puerto Badel. I delivered my carefully constructed sub-division community and expected kudos. Instead, the room was silent for a long time.

To break the silence, I turned to Alfonso. “Okay, what’s the deal?” I asked.

Alfonso stood up, slowly doffed his hat and looked at me. His words still guide my career in development and humanitarian assistance in many countries.

“Don Carlos,” he said politely, “we didn’t think you would listen.”

Because I had spent so much time in sensitive meetings about Puerto Badel, the community trusted me. We now had a working relationship. It was an honor to be included. What a relief I felt.

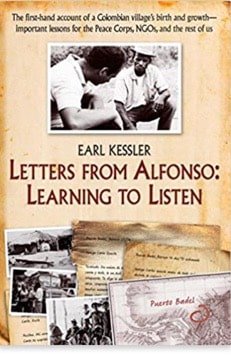

About 30 years later, while gathering material for my book, Letters From Alfonso: Learning to Listen, I wandered into the Augustin Codazzi mapping agency in Cartagena. There on the wall was a map of the Department of Bolivar with a dot for Puerto Badel. Our plan for a new town had become a real place! I almost puddled in tears of joy.

Alfonso had suffered the fate of many a community leader. He lost his wife, his house and his place in the community. He had moved to a new town, Arjona. When we met after these many years, we had a hell-of-a-reunion. I asked if he was still engaged in community work in his new home town.

“Esta Loco?” he said. “Are you crazy?”

However, Puerto Badel was on the edge of prosperity. There were substantial homes, jobs at the shrimp farm across the canal, a new fishing dock, a police office, and a bus connection on a new road to Cartagena or by motorboat on the old Canal del Dique. This town was Alfonso’s dream. It is the town where I learned to listen. It made me a different and better person.

Puerto Badel now faces the issues that many small towns must address—control of the environment, connectivity with Cartagena, cell phone reception, and teenage pregnancies—but subsistence is no longer their problem.