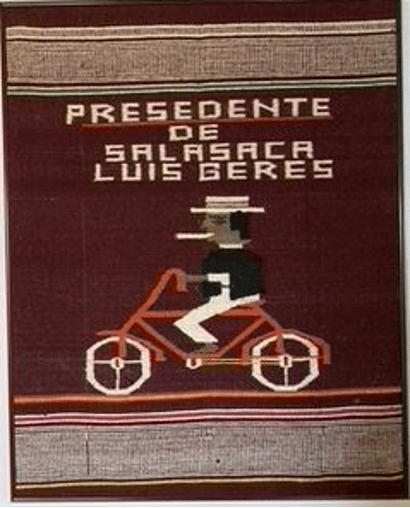

What I remember best about Lucho Jerez was his laugh. A giggle, really. And there he was on his new bicycle as he took it for a spin around the plaza in front of the church. Laughing nonstop. There weren’t many bikes in Salasaca in those days—it was 1966—and it was a treat for the children to see him riding around in circles. After all, he was the alcalde—mayor, judge, jury, and presidente. Giggling.

Lucho’s name is misspelled here, and I’d never seen him smoking a cigar. But the tapiz, or tapestry as it was called, was the work of one of Salasaca’s young weavers, Abram Chango. I think the kid just thought it was funny.

Abram was a member of the weavers’ co-op who created the tapestry that I purchased for myself. The co-op represented the leading edge of generational change in a traditional, Quechua-speaking community that otherwise lived like its ancestors had lived five hundred years earlier. The weaving program initiated by USAID a few years before I arrived as a PCV was bringing an infusion of energy and new wealth into Salasaca. A handful of cement-block homes with tile roofs replaced the traditional packed-mud-and-straw-roofed chozas. When I first set foot there in 1966, Salasaca was moving on up.

As a Community Development Volunteer, I had become involved in literacy classes, a syphilis-eradication program, and a few more modest projects. (One of those projects was to teach Lucho, who was illiterate, to sign his name.) Most of my time went toward helping the weavers market their handicrafts both in Quito and in the United States. I also accompanied Lucho and the other leaders of the community to the capital in a contentious court case. They went head-to-head with a powerful landowner and his lawyer, who had run for Vice President of Ecuador on a neo-Nazi ticket. But Salasaca won the case.

Before me, others had established the income-generating work that triggered Salasaca’s transformation. But it was Lucho, the young weavers, and others in the community who truly drove the change. Lucho’s daughter, Francisca (or Pancha, as she was known), attended secondary school, obtained a teacher’s certificate, and established an elementary and middle school. Pancha’s daughter (Lucho’s granddaughter), Mirian Masaquiza, has become internationally known. She is an outspoken and articulate human rights activist, advocating for indigenous women and girls at the UN and worldwide.

Salasaca had always stood out from its neighbors. The settlement straddles a spur of the Pan-American Highway, leading from the provincial capital of Ambato to the town of Puyo in the Amazonian Oriente. But the community had lived in Bolivia half a millennium earlier. They had fiercely resisted the Incas, who relocated them hundreds of miles northward to their present arid, highland location. However, Salasaca’s war-like reputation did not end with the relocation. It was one of the few indigenous communities in Ecuador that successfully fought off the Spanish. Thankfully, like USAID and my PCV predecessor, I was warmly received when I arrived there in 1966.

In 1994 and again in 2004, I returned to Salasaca for brief visits. The changes were remarkable. Around the plaza stood a small high school and a row of market stalls, where a trickle of tourists browsed through weaving and other handicrafts. Nearby were an Internet café, a tiny store that sold essential household items, and the office of a taxi service. I also saw Salasaca men driving pickup trucks. In every direction, two-story cement-block homes with wooden floors and red-tile roofs replaced chozas. And I learned from one of my few surviving friends that a handful of the weavers—no longer young like Abram—were going abroad to hawk their wares on the streets of New York, London, and other cities.

Lucho Jerez is long gone. He died, I was told, when a speeding car hit him while he was walking home beside the highway. The changes set in motion by his daughter and granddaughter—as well as by Peace Corps volunteers like me—are still there for everyone to see in Salasaca.