In 1966 I was a Peace Corps volunteer in the Sierra-highlands region of Peru – with another volunteer, Jack Hoffbuhr, a civil engineer. We were assigned to the program known as Cooperación Popular, the creation of President Belaúnde Terry. Our main activity was working with small communities to build better schools of local materials such as tapial (rammed earth) and adobe. The community provided the local materials, and the government program was supposed to provide corrugated metal roofing, doors and windows.

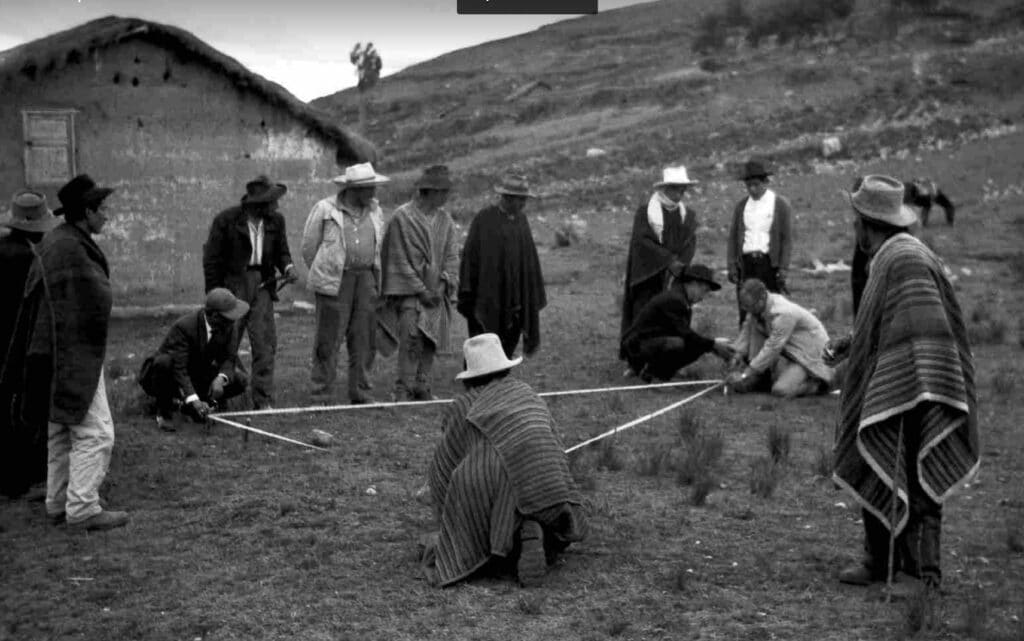

The program also provided cement for community reservoirs. On this occasion we were asked by two communities to survey a site for a reservoir because they desperately needed water. The local agricultural agent applied pressure to complete the survey. What we didn’t realize at the time was that so little water was flowing that a reservoir was not the answer to the problem. It would have taken about a month to fill and only about 10 days to empty. We concluded that we should never have conducted a survey in the first place.

We then told them that Engineer Leyva, our Peruvian supervisor, would make the final decision when he visited the site. We really hoped that he would propose a different solution to make up for our really bad mistake. I remember us thinking: “We have learned by experience – but what a bad experience and hard way to learn.” Supervisor Leyva visited and agreed with us. There was too little water flowing into the basin to build a reservoir.

When we returned from surveying the area, the people had already completed a substantial amount of the digging. We tried to tell them that this reservoir would never solve their lack of water, and therefore, we would not provide the cement to build the reservoir.

Leyva then used his unbeatable logic on the people. He said that they could have the cement for the reservoir, but that all their work would be for naught. It was not that he lacked the cement to give them, nor was it that he didn’t want to give it to them. However, it would be much better if they made cement bricks to line the canals, to keep the drinking water moving when it flowed. He a final bit of persuasion: a reservoir needs constant attention. The people would soon get tired of caring for it. Someone would then either forget to close the gate or be too lazy to trudge uphill to close it. Once it filled, the reservoir would simply empty rapidly.

Engineer Leyva strongly recommended that both communities focus instead on finishing their schools. As Leyva talked, I watched a change in attitude come over the people. When he finished, they seemed to agree that a reservoir was not the answer to their problem after all; the schools were more important. The effect of Leyva’s speech was like magic. We could only admire a person so experienced in working with the people of the highlands. Leyva was able to convince them with his skillful and understanding way of talking to them. Jack and I hoped that by the end of our two years in Peru, we would achieve a fraction of the Engineer’s skill at persuasion. Leyva treated these people as dignified human beings and did not talk down to them. As a result, they respected and admired Leyva—and accepted his logic. We knew that his understanding of their psychology is what we had yet to achieve.

This experience taught us that the long-term feasibility of the project should always take precedence over trying to please the people. Initially, this was a difficult concept for two young, idealistic Peace Corps volunteers to accept. What the people want and what is possible are not always compatible. We realized that part of our job was to be able to explain the difference in these concepts to the communities.

Afterward, Jack commented “I think the key lesson learned was you have to temper your desire to help with a large dose of reality. Don’t make promises before you understand the entire problem. That took a great sense of mission and the ability to laugh at ourselves.”