For over 47 years, these two dark-brown, glass beer bottles sat idly on the top shelf of my bookcase with handicrafts and textbooks from my career teaching English around the world. Now and then, I’d put these old bottles into the recycling bin. But moments later, I always retrieved them.

These 24-ounce bottles once held Zaïrois-made, European-style brews produced from

Belgian hops in Swahili-speaking eastern Zaïre. Simba, with the lion on the label, was one of the best—a blonde pilsner. Tembo, with the elephant label, was a dark, amber-colored beer much like Guinness stout and stronger than Simba.

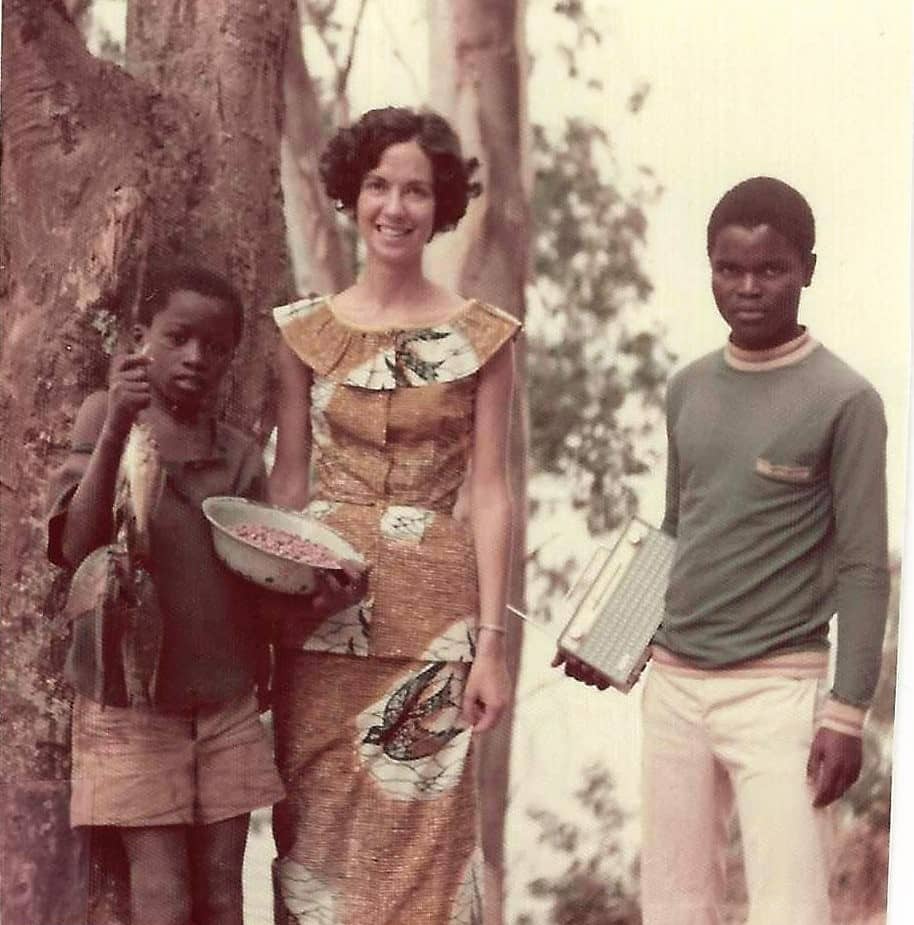

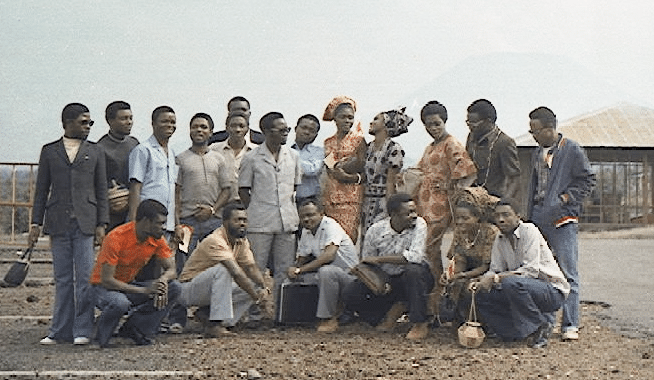

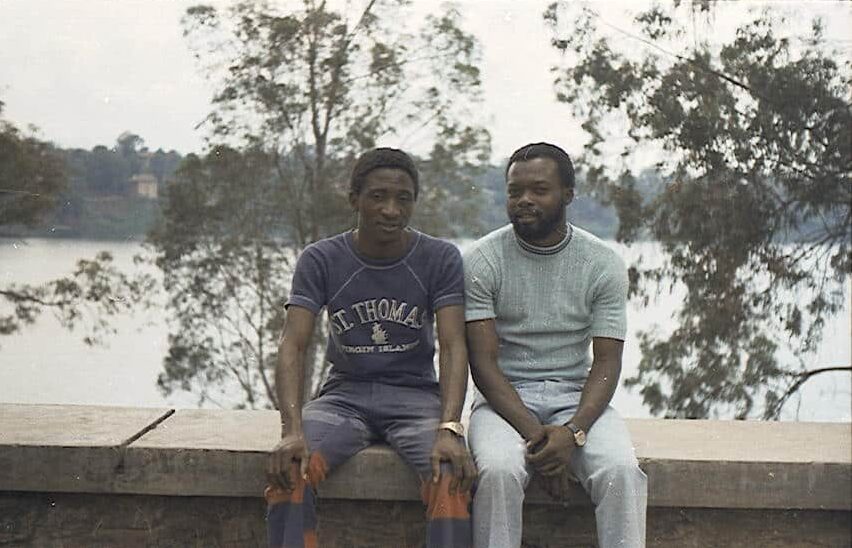

Before I started my two-year assignment teaching English as a Foreign Language at a Catholic mission school, I was a trainee at the Peace Corps Training Center in Bukavu, eastern Zaïre. There I met Kalombo and Makunya—two dynamic formateurs Zaïrois with specialized training from the Peace Corps to teach Americans French, local languages and culture.

These two men were just a few years older than most of us trainees so when they offered some of us with French fluency after-hours, informal classes in la culture Zaïroise, we agreed. The instruction usually took place at Le VIP, a second-floor nightclub where we newly arrived trainees learned about Zaïre’s spirit of joy, hospitality and grace.

On our first night at Le VIP I watched our tab grow to eight Simbas and Tembos and lots of snacks.

“How can we contribute to this bill?” I whispered to Mary, a trainee beside me. “We only have US dollars—no makuta.”

“We have to say something,” Mary whispered back.

I turned to Kalombo with our dilemma. “We’re happy to be here. We want to stay but we can’t pay. We only have American money. Can you take our dollars and pay with your makuta?”

Kalombo looked at Makunya, speaking in a language I couldn’t understand except for the occasional “Les Américaines.”

“This is American,” Kalombo explained to us. “When you go out, you pay or divide the bill. Not here. You cannot tell someone, ‘Let’s go out,’ and then tell them to pay or contribute to the bill. This is not right. We are responsible. When we invite, we must pay.”

This was the first of many lessons that began as soon as we reached the top of the narrow stairs to Le VIP.

With James Brown classics and Zaïrois music blasting, it was difficult to be heard so I did a lot of watching and listening. Kalombo and Makunya taught us to dance the cavasha to the beat of “Get On Up” and Zaïrois songs such as “Marie Thérèse.” They translated these songs, explaining the double entendres in the lyrics. From what I remember, Marie Thérèse was a sad love story with a lesson about infidelity and most Zaïrois music was filled with love stories that ended with a moral.

Each weekend throughout training, four to six of us gathered around a small communal table, drinking beer, eating snacks, and dancing. The table quickly filled with bottles ordered for the entire table, not for individuals. And our glasses were never left alone. If Kalombo was dancing, Makunya stayed at the table and vice versa—refilling our glasses, never leaving them alone or half-full.

Snacks were also communal. We shared brochettes, charcoal-broiled goat meat shish-kebobs served with pili-pili (chili peppers); small roasted, red-skinned arachides (peanuts). My favorite were samosas, small triangles of crispy fried phyllo dough stuffed with ground beef and a touch of pili-pili.

At night’s end before leaving, we gobbled up the remaining snacks and guzzled our beers, leaving a table of empty bottles and glasses—as politeness dictated.

I couldn’t recycle my Simba and Tembo bottles. They represent the socializing and negotiating—listening and learning—that the Zaïrois taught me. I am grateful to contribute them to the museum.