A volunteer searches for the best artisans and makes a true friend

By David Maxey

Mauritania 1987-1989

Late in my service to the Hopital de Nouadhibou, the first wave of violence began on our Senegalese border to the south. On the second day, I saw the cleansing begin in my city, the economic capital and Mauritania’s port city. Men carrying large wooden clubs and irons bars beat up Senegalese on the streets. On the second day, angry mobs turned on one of this West African nation’s ethnic minorities, the Pulaar.

My Peace Corps assignment at the hospital was to provide education and to assist wherever there was need and that included services for the handicapped. I had periodically encountered a beggar at the airport, the Catholic Mission, and the hospital who navigated the rocky terrain of this desert city crawling on his knees and hands with the aid of four rubber flip flops. His name was Sow Djibril. Sow had suffered a severe case of polio as a child and his legs were stick thin and not usable, his torso narrow, his arms weak.

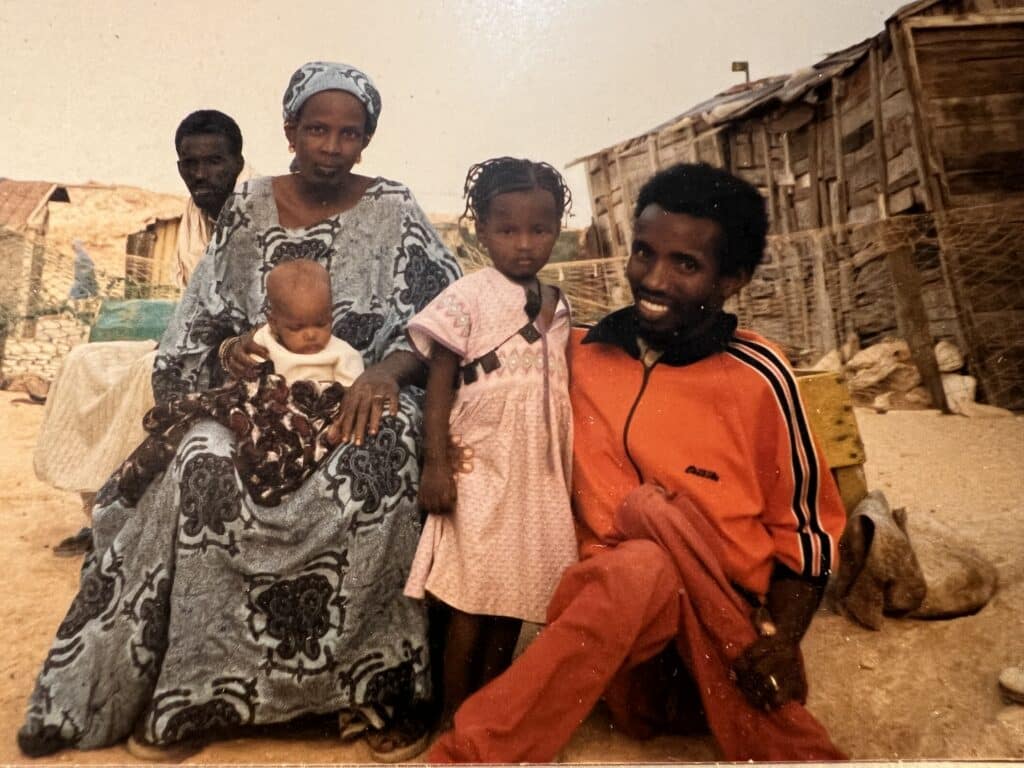

Sow Djibril offered me contacts within the city’s handicapped community that enabled us to eventually open a center for the handicapped at the hospital and that became the focus of all of my attention. One day, Sow invited me to have lunch with his wife and three children in their shanty. Djibril soon became my best friend and for about 18 months I ate lunch almost every day with he and his family; I usually brought the vegetables or gave money to purchase the vegetables.

I also had friends among all the tribal and ethnic groups represented in the city: white Moors, black Moors, Pulaars, Senegalese and other migrant and expatriate West Africans trying to earn enough money to escape from poverty and hoping to reach Europe.

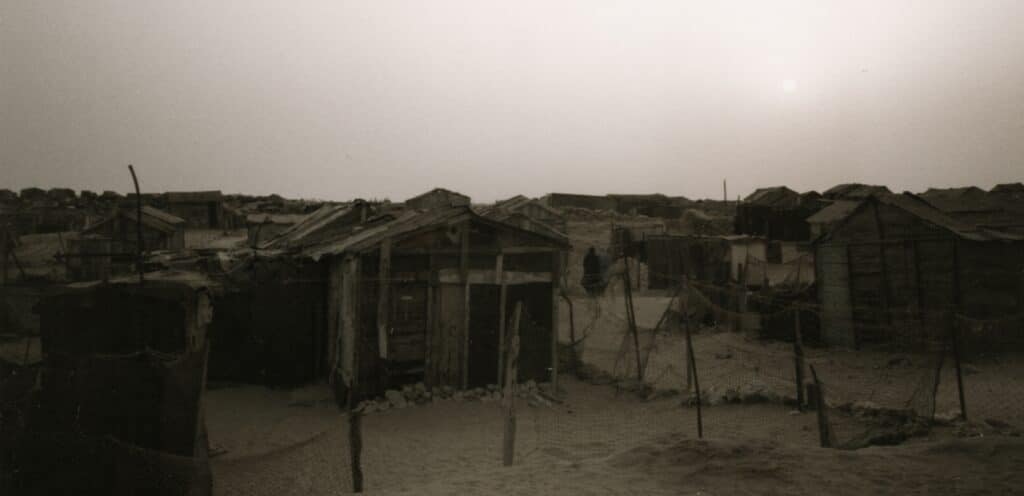

There is enormous poverty in Mauritania and I chose not to photograph that sad reality. But within every home I found glimpses of exquisite artisanal work. In those glimpses was born my desire to show my friends and family not the grim poverty but what I called best of the best of Mauritania’s artisanal work to show to my friends and family when I returned home.

One of my favorites is an amazing tea pot of Tuareg design, one of three I had made. I kept one and gave one to my parents and the other to my grandmother.

Teapots

Tuareg teapots were the equivalent of a fine china teapot, used mostly for truly special occasions and for guests. I discovered a small shop where I asked two craftsmen to make three pots while I watched them work. I told them I would take the pots to America. I had brought in half of a baguette with double butter and double jam that we shared. They brewed tea that we drank while they worked. The application of molten metals fascinated me. I watched them etch the star and crescent moon of Islam above the spout to make each of their pots unique. What an enormous compliment they paid to me.

Wooden bowl for zrig

The zrig bowl is another example of Mauritania’s best. The bowl is beautifully hand-crafted with a manufactured design stamped along the sides of the bowl. Zrig is a mix of water, milk, sugar and sometimes orange soda. It is a very welcome and refreshing drink when the winds of the hot Sahara fill with dust, sand and grit. The dust storms blow at temperatures sometimes approaching 110 degrees Fahrenheit.

Gri Gri bracelet

Shortly before I left Mauritania in December, 1989, Sow asked a religious leader to make a leather bracelet with an embedded cowry shell for me. It is called a gri gri and it bestowed on me protection for my travel home; he told me it would protect me only during the time I was traveling, but not before, and not after. I was familiar with most types of gri gri that were similar to the Catholic scapula, square pieces of leather worn around the neck. When I arrived home I learned my bracelet had magical powders and verses from the “Qoran” hidden within the leather. Sow knew I was Roman Catholic and his gri gri was Sow’s gift of acceptance of my faith and it showed his care for me that I would be given such a particularly Muslim kind of protection.

All of these items represent acceptance, thanks and generosity by so many of the Mauritanian givers who live impoverished lives in the harsh and unforgiving Sahara desert. I am deeply honored by each of their gifts.

The author works as a Department of Justice fully accredited immigration counselor for Commonwealth Catholic Charities of Virginia in Roanoke.