Bags of Money and Nothing to Eat

Debby Prigal

Ghana 1981-1983

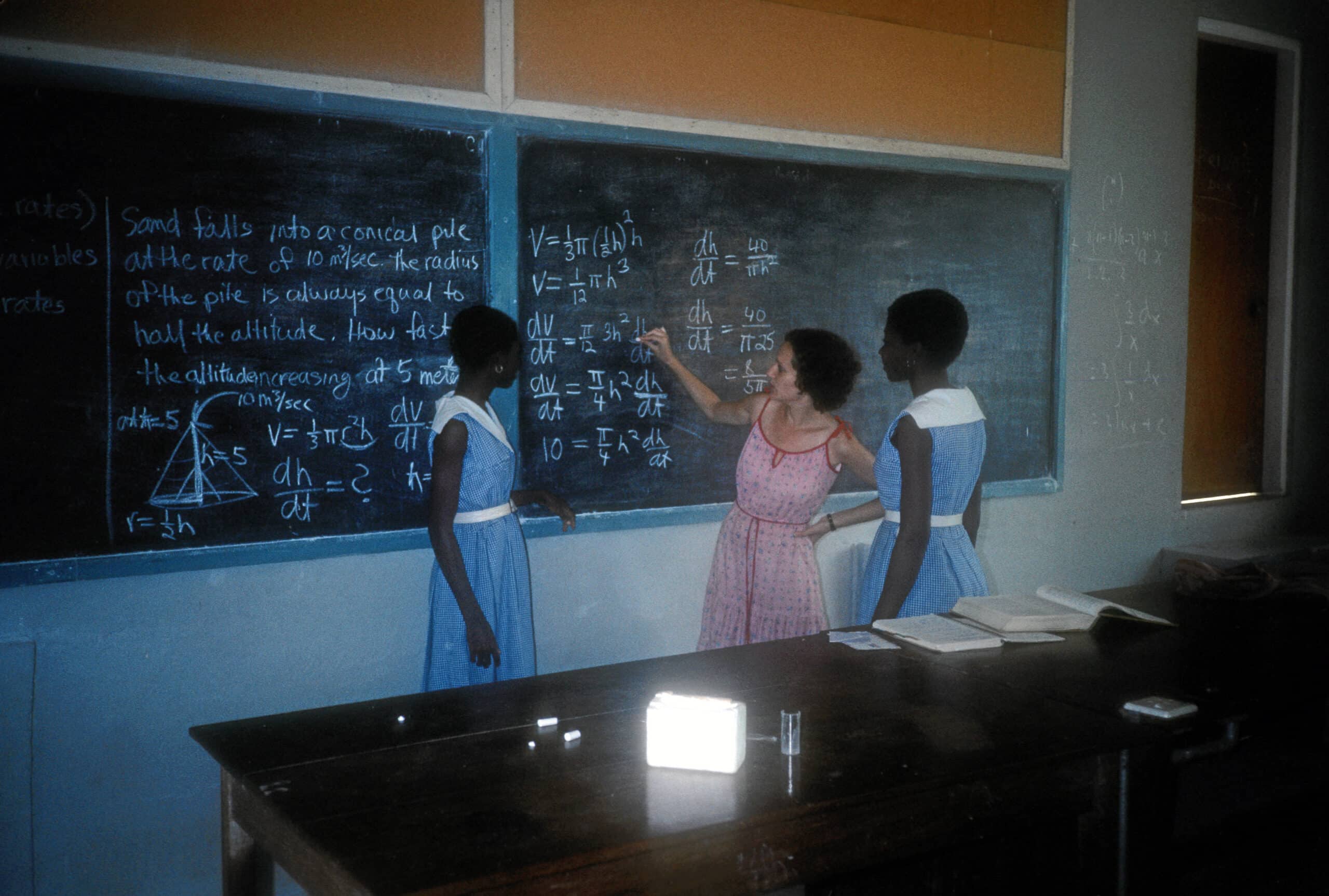

I taught high school math at Our Lady of Apostoles Girls’ Secondary School. Ho was the capital of the Volta region in eastern Ghana, near the Togo border, and had two high schools, a hospital and a stadium. Not really the bush.

Throughout my Peace Corps service, Ghana suffered famine, shortages, and rampant inflation. The official exchange rate was 2.75 Ghanaian cedis to the U.S. dollar. The black market rate was 35 cedis to the dollar when I arrived in July 1981, and 120 to the dollar when I left in June 1983. The Peace Corps used the official exchange rate, per U.S. Embassy policy. Most people (Ghanaians and others) were amazed that Peace Corps would do anything so stupid.

In stateside training, we were told that changing money on the black market would earn us the “Pan Am Award” – a one-way ticket home, the same as if we were caught with illegal drugs. However, as soon as we arrived in-country, we realized that since we were paid at the official rate, our buying power was so limited that we could not afford a basic Ghanaian diet.

Peace Corps headquarters exchanged $350 for each of us but because it was at the official rate, my living allowance was worth around $60 a month when I arrived and around $18 a month when I left. PCVs in neighboring countries got $350 in actual value. If I had two eggs for breakfast, I had no other money for the rest of the day. Togo PCVs had a joke: “How many Ghana PCVs does it take to change a lightbulb? Five – only one to actually change the bulb, but one to find it, and three to pool their cedi paychecks to buy it.”

Ghana PCVs had to trade their own dollars on the black market just to feed themselves a basic African diet, even though they were told they would be sent home if caught. Volunteers who did not bring dollars with them, even though we were explicitly told not to, had to borrow from other PCVs and have their families in the States reimburse those families. However, no one could admit this out loud because they would be sent home.

We soon realized that virtually everyone, Ghanaian and expatriate, changed money on the black market. My headmistress said, “Don’t ask what the bishop does with the dollars he gets from Rome.” Many PCVs didn’t bother to pick up their living allowance checks, as they were worth less than the bus fare to the office.

Ghanaian currency was so worthless that when thieves broke into houses, they would steal pots and pans, towels and even the soap, and not bother to take the cedis. People joked about using it as toilet paper since they were easier to find. I never actually did, since Peace Corps provided us with a subscription to Newsweek, and that was enough.

Virtually all trades used the 50-cedi notes (worth less than one dollar), even though you still needed bags and bags of cedis. To try to end some black market transactions, the government told people to bring 50-cedi notes to a bank. Some people brought in massive piles, but many dumped their worthless notes in the trash.

Cedis looked great because they were printed abroad. However, the Ghanaian government often did not have hard currency to have them printed. Meanwhile, the government run Cocoa Marketing Board needed cedis to pay the farmers in order to sell their cocoa abroad.

Rumors started that the 20-cedi note (worth about 30 U.S. cents) would be recalled. People panicked and brought piles of these notes to banks. For some it was all the money they had. There were huge lines with people pushing and shoving as harried clerks tried desperately to deposit the money. I walked around and saw a crazy “reverse banking panic.” For me, it was unsettling, for many Ghanaians it was horrible.

The next week, the farmers were paid – with the cedis deposited in the panic. This happened again and again. Rumors started, people rushed to deposit cedis and then the farmers were paid with those cedis.

When PCVs COSed the U.S. Embassy allowed us to convert cedis (supposedly by selling things) into $U.S. dollars at the official rate, basically the reverse of what we had suffered during service. I changed a few dollars into cedis and took that wad to the Embassy and got $200. It was the only benefit we got after two years of not being able to feed ourselves.

I kept some cedis to remember the crazy currency panics and Ghana’s economic collapse.