The hat is just a bunch of little burrs stuck together with a fluffy black feather on the bill, but it does stay on your head. I brought it home from Somalia and carefully preserved it for over half a century now. It reminds me that we are often oblivious to events around us.

One afternoon, I took a trade truck from Hargesia back to my teaching post in Arabsiyo and found a seat on a wooden box. Although the truck was crowded, no one else sat on the box. “Your mother must have offended a jinn,” a woman nearby remarked, probably referring to my white skin and red hair. “Only a jinn would make a person the same color as the devil!”

As the truck lurched over a desert track, I kept feeling a puff of hot air on my leg. I ignored it, but then something licked my ankle. When I peered into the crate I saw a lion, suffering from the heat and nearly unconscious. The Somali would not sit anywhere near the lion, nor would they offer it food or water.

Several men on horses appeared. They signaled for the driver to stop and shouted something I didn’t understand. After everyone got off the truck, I pried up the top of the box, wet a corner of my scarf with water and lowered it to the suffering animal.

Angry at the abuse of this poor lion, I leaned over the edge of the truck and banged my shoe on the side. “Wham-a hii?” I shouted. “What’s going on?” A horseman quickly rode over to see what I was shouting about. “Muga-Ah, what’s your name?” he asked.

“Jeanne,” I replied. “Muga i goo waa Jeanne.” He stared at me and tightened his hands on the reins of his horse when the lion, revived by the water, tried to sit up in the box.

“Muga-Ah?” I asked him, enjoying his surprise when he recognized the truck’s cargo. “Who are you?”

“Shifta, Wa Shifta,” he replied. He removed his hat and handed it to me—the same hat of stuck-together brown burrs I’ve kept all these years. He signaled his men and they rode off into the desert.

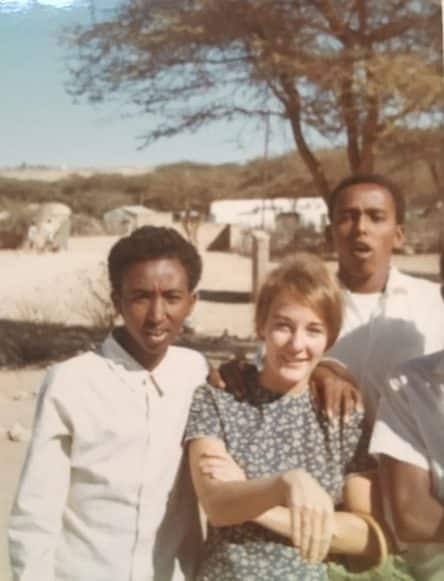

When I got back to my house in the village of Arabsiyo, headmaster Abdillahi visited me with Subti and Abdul Kader, the two other teachers at our school.

“Everyone is talking about you, Jean,” he said, shaking his finger in my face. “Do you Americans know about the Shifta?”

“No.”

“They are terrorists fighting in the border dispute between Somalia and Ethiopia. These Shifta were planning to rob the truck. Didn’t you see the guns? You even banged on the truck with your shoe and insulted them.”

“I didn’t mean to insult anybody.”

“Showing the bottom of the shoe is insulting to Muslims, don’t you know that?”

Then Abdillahi laughed. “This Shifta had never seen a white woman so closely before. He saw that you were not afraid, and you were sitting on a lion. He thought you might be a jinn and ran away, like a hyena!”

“That’s not what happened,” interrupted Subti. “There is a story in the Qur’aan about Mohammed and a prostitute at a well. She saw a thirsty dog, dipped her shoe into the water and gave it to the dog. Mohammed said her sins would be forgiven because of her kindness. When the Shifta asked who was on the truck, the driver told him it was the American prostitute. The Shifta must have remembered the story from the Qur’aan. He thought you brought a message from God.”

“I heard a different story,” said Abdul Kader. “The Shifta saw this white woman and asked about her. ‘Jean, that’s Jean,’ the passengers told him. He thought they said you are a jinn. He gave you his hat so you wouldn’t put a spell on him.’

For over fifty years, this little brown hat has kept me humble about my own opinions. We see through the lens of our own background and culture. Even under the bright African sun, we walk in darkness.