In some ways, being a Peace Corps volunteer in Ecuador was less challenging for me than for most of the volunteers in my group. I was born in the Republic of Panama and grew up speaking Spanish. Working as a health care worker in Brooklyn—a place that attracts a large number of Spanish-speaking people—I spent much time interpreting Spanish to English. During our training in Quito I was exempted from Spanish classes.

Upon completion of orientation, I was assigned to an area where the fetal and childbirth mortality rates were extremely high. This was a fantastic assignment, considering my preparation as RN/CNM and long experience working in under- served communities.

The welcome mat was not obvious during my first weeks in Pimampira. The local Catholic pries had cautioned the community that I was an evangelist. Once I became aware of this, I decided to attend Mass. I sat in the back row, and went to the altar to receive communion. The word spread in the community. The priest became a friend and large numbers of women came to the clinic for prenatal and postpartum care.

My responsibility included travel to outlying villages such as Chalguaycua and Sanchipamba, inhabited mostly by indigenous people. There I gave talks about sanitation, nutrition and the impact of hygiene on health. By gaining the confidence of these people, I was able to identify the local midwives and provide information that led to slow—but visible—changes. Ultimately, these efforts reduced the number of infections in these communities.

It was normal for people in Ecuador to arrive late for appointments. By offering small treats to those who came to meetings on time, I was able to gradually improve their punctuality.

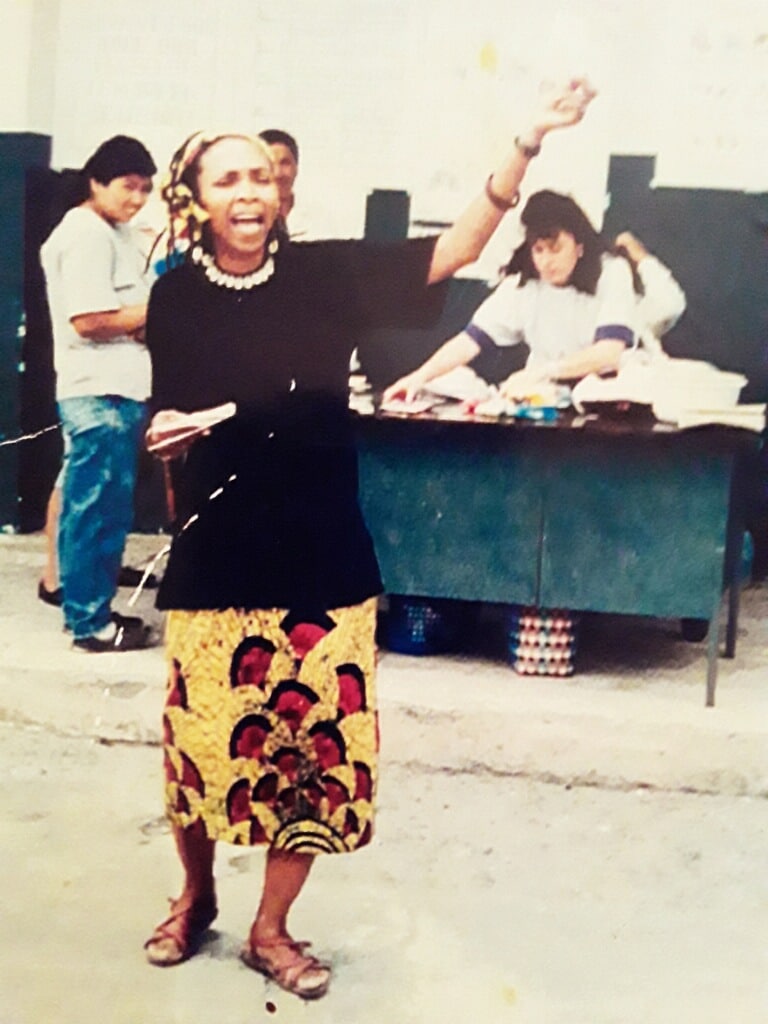

Aside from my responsibility to provide services to the clinic in Pinampira, I visited the black community of Chuga — referred to as morenos and “lost people.” These were some of the most beautiful black people I’ve ever seen.

After much discussion with a charity that sponsored a clinic in this community, I was able to relocate the clinic from a hot, desolate, dirty spot of pavement to a suitable location. The morenos came to see me in large numbers for pre- and post-natal visits.

Boosting self-esteem was an important part of my sessions. I said to them, “You folks look like me. I’m not lost, and neither are you. In this community, we have problems that we’re going to solve together.” Instead of drawing water downstream where the animals drank and garbage accumulated, I told them to draw their water further upstream and boil it. With simple measures like these, I began to see their health improve and illnesses decrease.

Everywhere I went, I talked about diet, washing hands, and basic sanitation. Walking behind two women, I heard one tell the other, “Never serve rice and potatoes together—too much starch. Rice and tomatoes is better.” After a talk at a school in Pimampiro, a young boy followed me out of the classroom and said,“You told us boys have two eggs, but I have three—and one of them hurts.” He had a hernia, and I was able to arrange surgery for him.

Finally, I was able to persuade merchants to support the cost of large health fairs in local schools. Another volunteer and I worked with school children to hold health fairs in on Saturdays. They were a huge success.

One of the biggest challenges of my Peace Corps experience was the lack of supplies. I was responsible for training and supervising thirteen mid-wives. Over time we started to see significant change. Fetal and maternal death rates began to decrease.

Besides my ability to speak Spanish, I might have enjoyed another advantage over my fellow volunteers. As a black American from Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, I understood that poor people usually have to fight to get what they deserve. The Peace Corps didn’t teach me this. Life did.