BOMBING

One afternoon, in full daylight, the anti-aircraft guns began firing. I heard the scream of a bomb. From past experience I knew it was coming toward me and I had no chance to reach the bunker. I looked around the room and found no cover. The best I could do was lie down on the cement floor and cover my head with my hands. I was in the passenger waiting room of the Biafran customs office at the end of the runway and no doubt it was a choice military target. The intensity built to a scream much louder than anything I had heard before. I said, “I’m sorry, Mom.” No child should precede its parent in death.

The scream passed right overhead, rooftop level, and continued away. It was not a bomb. It was a Nigerian Air Force MiG that had flown right down the center of the runway and released its bombs in the marketplace in nearby Mgbidi.

RPCV GOES HOME

Three years before the bombing of Biafra began, I taught English at Ohuhu Community Grammar School near Umuahia, a town in Eastern Nigeria. As I neared the end of my Peace Corps service, pogroms and mass killings of Igbo people started in other parts of Nigeria and Igbo refugees began pouring into the Igbo homeland in Eastern Nigeria. I returned to the United States with the memory of soldiers guarding Nigeria’s airports.

I followed the news of Eastern Nigeria’s secession from Nigeria, Biafra’s declaration of independence, the Igbos’ war with Nigeria, the Nigeria blockade of Biafra, the mass starvation of Biafrans—mostly children—among the people I had once served.

No country would intervene. A worldwide group of churches formed Joint Church Aid and mounted a humanitarian airlift of food and medicine. The airlift operated at night to avoid the Nigerian MiGs trying to shoot down the planes. The four-engine transports landed on a stretch of darkened road in the rain forest without radar. I was one of four Nigerian RPCVS who UNICEF recruited to volunteer as cargo masters, expediting the swift unloading of supplies. We chose to once again serve the Igbo communities where we learned Igbo local culture and the power of community.

MY KOLA LESSON

I still remember Mr. Ihukwumere who taught history at our Ohuhu Community Grammar School. Mr. Ihukwumere taught me about the Igbo culture. He was a tall and heavyset man who spoke English well. While other faculty colleagues wore European-style slacks, collared shirts and and leather shoes, Mr. Ihukwumere wore a native wrapper and walked in sandals with a slow, easy gait.

Mr. Ihukwumere invited me to walk to his village one sunny day for a meeting that took place in a large mud-walled structure with a peaked roof of woven palm fronds. He led me into a large dark room. My eyes twitched from the sting of wood smoke and as I adjusted to the dark, I saw a large circle of men, some young, many old, seated in silence around the wall of the building. All were dressed in customary wrappers like Mr. Ihukwumere.

Opposite the door sat the headman of the village, the member of the village clan who holds his position by merit, not heredity.

Igbo enwe eze. The Igbo have no king, as the saying goes.

I was seated to the left of the chief, about 120 degrees from the door, next to Mr. Ihukwumere. When I sat down a man approached the chief with a plate containing several kola nuts and a knife. Using the knife, the chief separated the nuts into their lobes. The plate was passed around and everyone took a lobe. I chewed mine as the others did. It was very bitter, but I ate it, feeling that this was a particularly important ceremony in Igbo culture.

Next, a man handed the chief a lump of chalk. The chief took it in his right hand and made two parallel marks across the inside of his left wrist. Then he passed the chalk around the circle. Each man made the same marks. So did I.

Mr. Ihukwumere leaned toward me and whispered.

“In the days of the slave trade, if a stranger walked through the village, he might be snatched and sold to the slave traders. But if he had the chalk marks on his wrist, it meant that he was under the protection of the village and he could not be taken or harmed in any way. Other versions of the chalk mark are used throughout Igboland.”

I felt the weight of this honor. The ceremony had been held for me. I was safe in their land.

SAVED BY A KOLA NUT

During my later service as a loadmaster in the Biafran airlift, I was arrested under suspicion of being a Nigerian spy and was detained in a small building at the end of the runway in Biafra. The Biafran Air Force Commander interrogated me. He was thorough and professional and never threatened me. A few days later, a young Customs worker would sometimes sit and chat with me. He seemed very friendly. He may have been sizing me up for the commander. I talked about my Peace Corps days, and he told me about his family.

While I was detained, I asked him to buy some kola nuts, oji, and palm wine, mmanya nkwu. We invited a few others to join us outside in the warm African evening. We broke the kola according to custom and shared it.

“Onye wetara oji, wetara ndu.” He who brings kola, brings life. We got very friendly drinking the palm wine.

Many years later, an American mercenary who had worked for Biafra told me that they took suspected spies and saboteurs to my school which had become Biafra’s Military Intelligence Headquarters. That’s where they shot them, next to the garbage pit right behind the house on the school compound where I lived. They didn’t send me to Umuahia. They released me. I was not a spy. I was safe in their land.

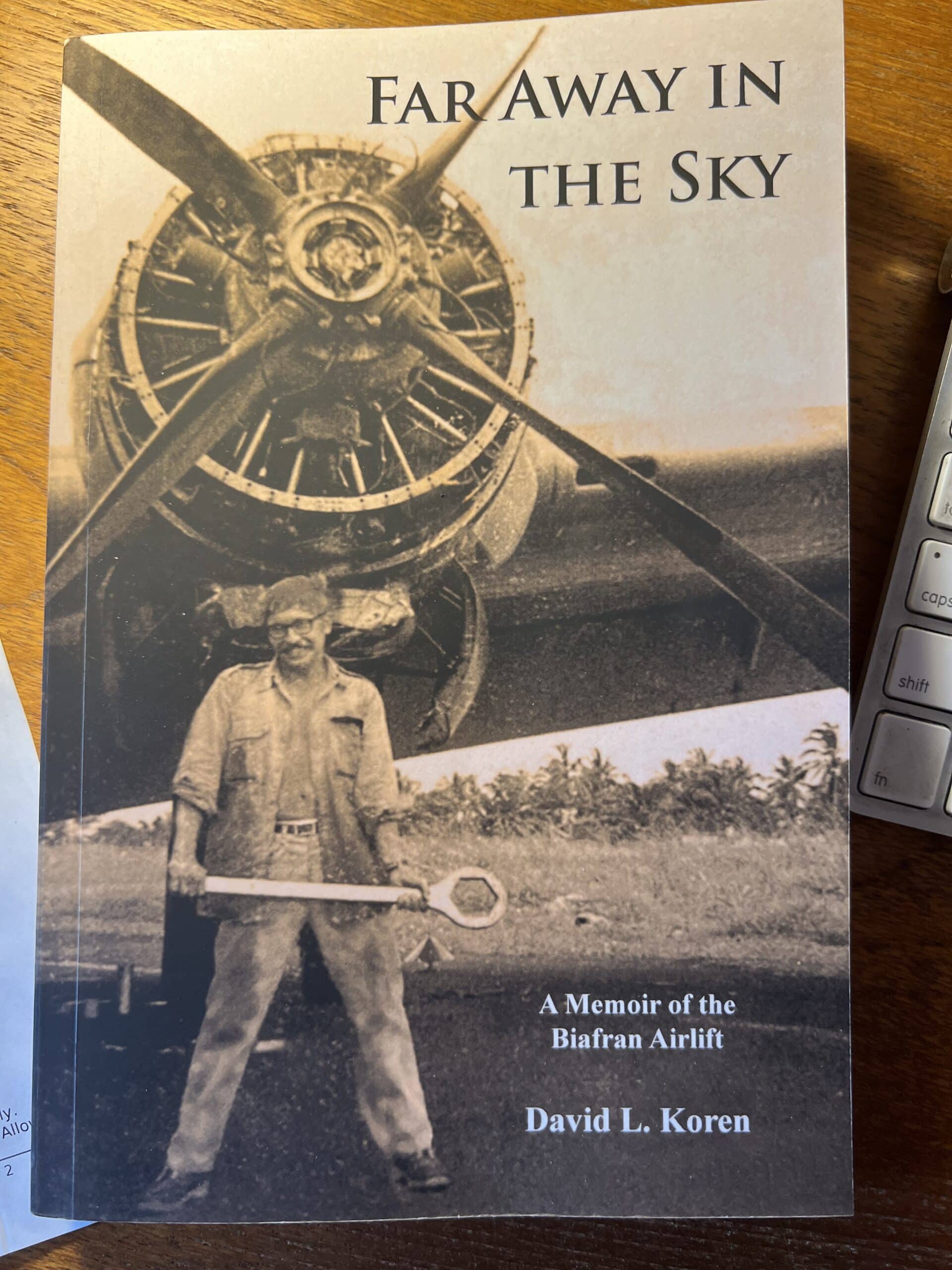

This story is adapted from the book, “Faraway in the Sky: A memoir of the Biafran Airlift,” written by David L. Koren, based on cassette recordings he made as a volunteer, published by Peace Corps Writers. A copy of his book is in the Museum’s collection.