My wife Lois and I served with the first contingent of Peace Corps volunteers to Liberia in the interior town of Tappita. The local people had raised the money to build a school and hired a contractor from Ivory Coast, but he absconded with their money. They raised the money again. This time, the men and women of the community toted bags of cement on their heads 200 miles from the coast through the rain forest. I taught science and mathematics to grades 7–9, and my wife taught language arts to grades 4–8. Lois was on virtually every committee the principal suggested including operations and school nutrition. The school soccer team, which called itself, Walking Death, picked her to be their sponsor. She started a community newsletter and organized a girl’s track team.

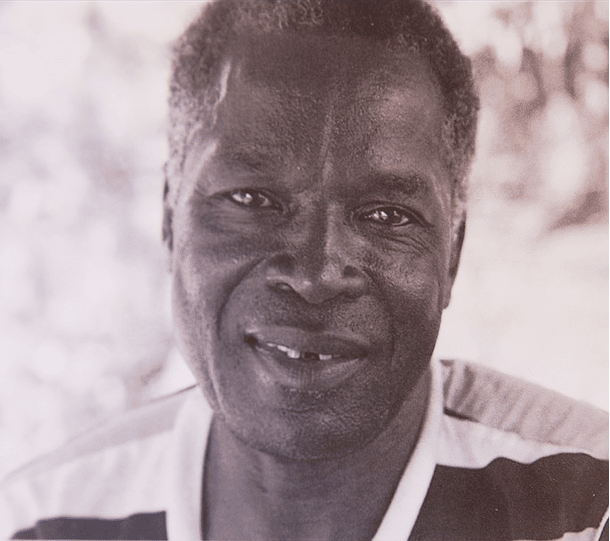

While buying eggs from the Baptist mission nearby, we discovered something way more interesting than eggs, —a wood carver named Dru. Intrigued by his work, I would trudge up the mission hill above town, no longer to buy eggs, but to sit and talk with Dru outside his thatched hut while the shavings flew. I was reading Irving Stone’s The Agony and the Ecstasy. Michelangelo supposedly could see the carving in a block of marble. I wondered if Dru, like Michelangelo, could see the finished product in a piece of wood. Dru said he could turn it around in his head and see every angle. When we met, he was about 40 years old and already noted for his work, although I didn’t know it at the time. Years later, we would discover his work at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Dru—born into the Krahn tribe in the village of Kpeaple along the Liberia/Ivory Coast border—spoke Krahn, Gio as well as fluent English. He had attended the Baptists’ school in Tappita as an adult.

Four Krahn Passport masks carved by Dru.

While watching him work on those pensive afternoons, I learned that Dru came from a family of carvers. Even as a child he knew he would become a carver. As a young man, he sold his pieces at the Firestone rubber plantation in Harbel until he was called to the Krahn bush country to become a ritual mask maker.

Five years before I met him, Dru had left his ceremonial work to take up Christianity at the Baptist mission. He intended to abandon mask making but the missionaries urged him to continue carving to support himself. He did—but only souvenirs like antelope heads and elephants. Selling masks, he feared, could bring retribution from the bush people. After many long afternoons of talking with me, he allowed me to see one of his sacred ceremonial masks.

He said, the Krahn wouldn’t know, and to me it would just be wood.

The Chimpanzee circumcision mask is the mask he brought out that day, and it bowled me over. It is the first work I acquired from Dru. This mask is carved from a fairly dense wood, possibly mahogany, making it heavy to wear. It would be worn by a Gle (spirit) dancer visiting boys in a Poro puberty ceremony camp. The dancer wears the mask over his forehead in a stooped position looking through the mouth. He speaks in unintelligible sounds translated by a chaperone. Boys of the Bantu-speaking people go to secret forest retreats. They spend months acquiring the knowledge of adulthood from the Gle and then return, reborn as men.

I was also able to buy a ceremonial white eye mask. This resembles the Gio Gle Ko To, a figure who arrives during the hungry time before the upland rice harvest. Ko To whirls and whirls, singing in a high-pitched hypnotic voice that bewitches the listener and distracts from hunger and need. Ko To wears a raffia tent-like garment from the neck to the ground.

Our friends and neighbors made it clear that the Gle does not wear a spirit mask; he becomes the spirit. The mask possesses him. When I saw these masks, I knew I must have them—both for their artistry and to remember my dear friend Dru.